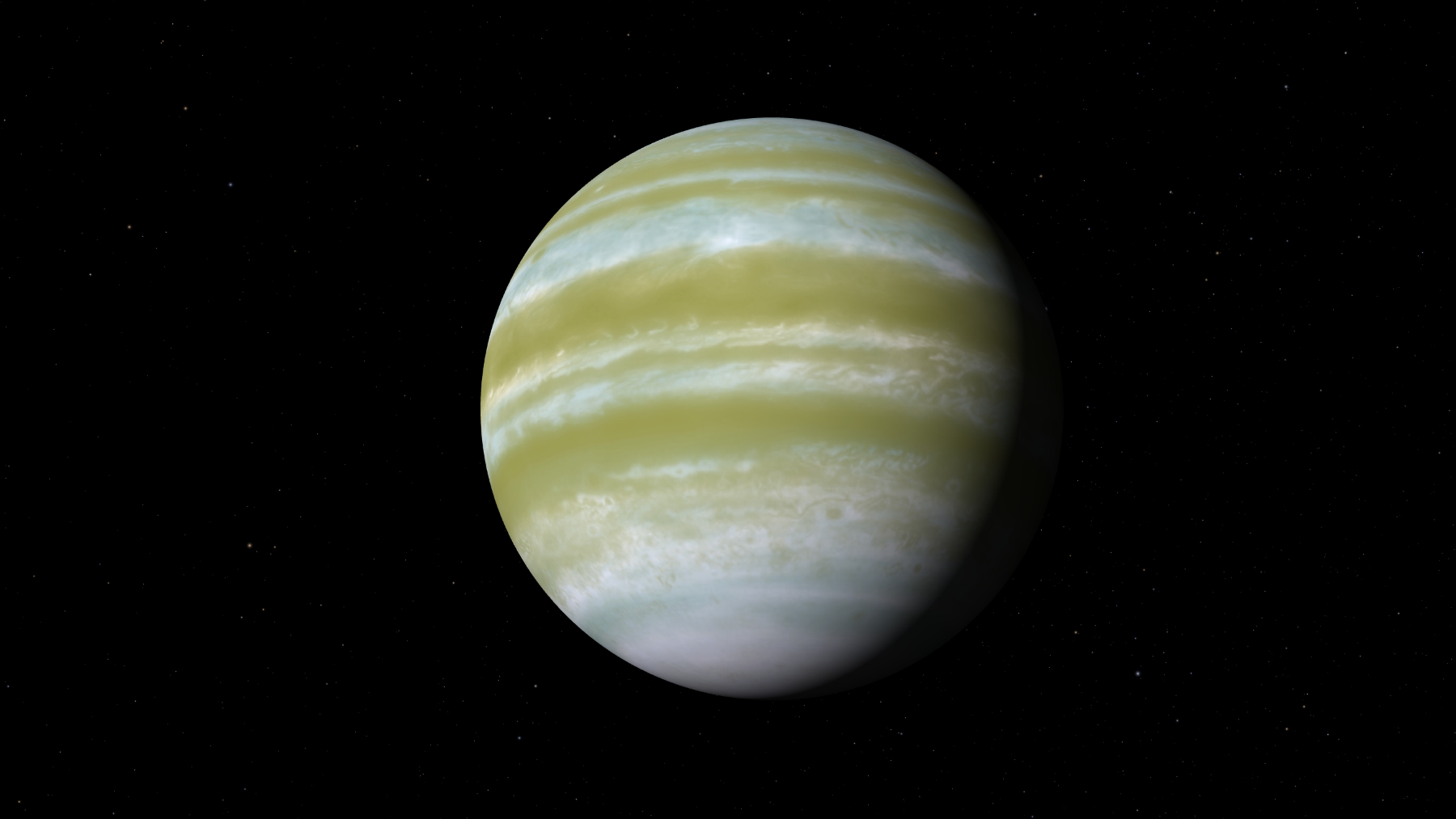

What if we told you the NASA has found a planet were we could potentially dip our toes in a few generation? Meet TOI-270d, the first recorded exoplanet with a high probability of having a hydrogen ocean underneath its opaque atmosphere.

TOI-270d, always so timid, was first spotted by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). It was nothing but a tiny dot in the sky. Every 11.4 days, the planet crossed in front of its small red-dwarf star and dims it by a hair; that repeating blink is how astronomers knew a world was there.

After some investigations, scientists calculated it had pinned a mass around of 4.8 times Earth and a radius a little over twice Earth’s, which puts TOI-270d in the “sub-Neptune” category. Once they had their data, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was used to study the planet gases and radiation.

Why scientists think TOI-270d might have a global ocean

When JWST spread that filtered starlight into a spectrum, teams reported methane and carbon dioxidein a hydrogen-rich atmosphere. Some studies also noted a lack of ammonia, which, if an ocean were present, could dissolve out of the air. Put together, that chemistry lines up with theoretical “Hycean” worlds (planets cloaked in hydrogen with a deep ocean underneath).

While these clues don’t necessarily prove there’s an ocean with tides and waves like the ones we have back at home, the TOI-270d’s composition does leave some possibility for an alien ocean.

Where TOI-270d is and what it’s like

The planet orbits 73 light-years away in the southern constellation of Pictor. It circles a star about 40% the size and mass of our Sun. Because it huddles close to its star, a “year” there is shorter than two weeks.

On paper, TOI-270d is beefier than Earth but far smaller than Neptune—a middleweight that likely holds onto light gases. That’s perfect for JWST’s methods, because a puffy atmosphere puts a bigger chemical “signature” into the starlight, making TOI-270d easier to study than a bare rock.

Could we colonise TOI-270d?

Although it might be fun to imagine a ship heading to TOI-270d (like in the movie Passengers), colonisation is not on the table. A hydrogen-rich sky with methane and carbon dioxide is not breathable, and the deeper you go, the pressure and temperature likely soar. It is simply to hostile for human life, even with technological advancements.

If the planet is Hycean, the “ocean” could be super-pressurized and hot, not a blue Earth-style sea. And if the alternate model is right, TOI-270d may be a giant rocky world wrapped in a scorching, metal-rich atmosphere. Either way, a pleasant shoreline is not in the cards. At most, far-future engineering might imagine high-altitude platforms or orbital stations, but surface living looks like a nonstarter.

The debate around TOI-270d

Here’s the twist: a Southwest Research Institute–led team modeled the same kind of data and came to an entirely different conclusion. And a fresh Astronomy & Astrophysics preprint shows how changing assumptions about clouds, temperature profiles, and chemistry can flip your answer from “Hycean-ish” to “hot rocky with a deep atmosphere.” That’s normal science in action: with each JWST pass, the error bars shrink, and the community watches for which model survives.

For TOI-270d, the next steps are more spectra at different wavelengths, tighter stellar activity checks, and consistent retrievals across teams.

TOI-270d sits in a sweet spot: close enough to be bright, big enough to have a detectable atmosphere, and chemically interesting enough to keep everyone honest. It could be our first real look at an ocean world beyond the Solar System—or it could teach us why some sub-Neptunes only pretend to be watery when you read their skies from afar. Either outcome is a win, because TOI-270d is already helping researchers stress-test their tools and sharpen the rules for spotting oceans light-years away.