Unprofessional abortion referral practices are a threat to person‐centred abortion care. Evidence globally shows that unprofessional abortion referral practices can generate misinformation, communicate judgement, and hinder timely access to care — causing distress and harm to abortion seekers.1,2,3,4,5,6 These harmful referral practices occur across the health care workforce and are not limited to individuals claiming a conscientious objection.1,2,3,4,5,6 This suggests a need to define best practice for abortion referral and encourage professionalism in referral practices. Addressing this gap, this perspective article: (i) applies the principles of medical professionalism to abortion referral, (ii) proposes a minimum standard for professional abortion referral, and (iii) identifies strategies across the health system to promote person‐centred referrals.

Does guidance exist to promote professional referral practices?

Policy discussions around refusal to participate in abortion care (eg, conscientious objection) often focus on whether the health practitioner is willing to refer an abortion seeker to a willing provider.5 Refusing practitioners who do refer are assumed to be acting in line with professional standards, while those who do not refer are generally seen as unprofessional and obstructing care. Although this focus on willingness to refer is warranted, particularly as referral is legally obligated in many jurisdictions,5 we argue that the act of providing an abortion referral is necessary but not sufficient to meet professional standards. How a referral is carried out is also a critical component of the professional obligations towards abortion seekers.

Abortion‐specific guidelines are clear that practitioners who refuse to participate in abortion should refer their patients onwards. For example, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical guideline for abortion care states that practitioners who have a conscientious objection to abortion should “inform the woman how to access the closest provider of abortion services within a clinically reasonable time” and “must not impose delay, distress or health consequences on a woman seeking an abortion”, but does not provide further details.7

Medical codes of conduct provide additional guidance for ethical and professional behaviour, but these are often broadly worded and cover the entire scope of practice. The Medical Board of Australia Good medical practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia states that all providers should act in their “patients’ best interests when making referrals” and that their personal views should not “adversely affect the care of your patient or the referrals you make”.8

There is also specific guidance for conscientious objection. The Australian Medical Association’s position statement on conscientious objection tells practitioners to treat patients with “dignity and respect”, “minimise disruption to patient care”, and not “impede patients’ access to care”.9 The code of conduct similarly states that a doctor’s conscientious objection should not “impede access to treatments that are legal”.8

Despite the relevance of this guidance, there is ample evidence of a disconnect between real‐world abortion referral practices1,2,3,4,5,6 and the principles outlined in professional codes of conduct and clinical guidelines (Box 1).7,8,9 Strategies are urgently needed to ensure that practitioners refer patients for abortion in a professional manner.

A spectrum of abortion referral practices

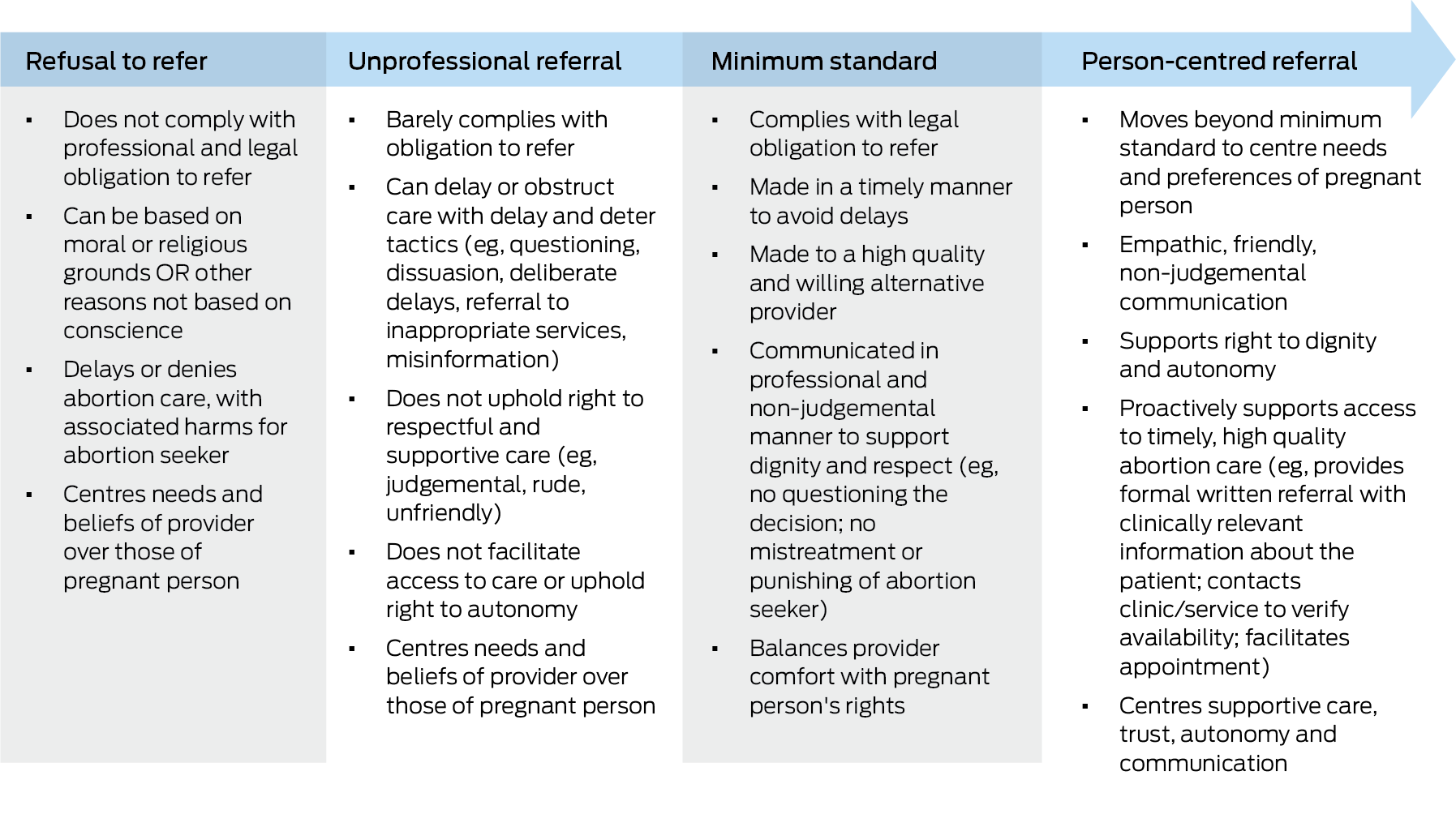

Applying principles of medical professionalism to abortion referrals, we present a spectrum of practices, from refusal to refer to person‐centred referral, and propose a minimum standard for professional abortion referral (Box 2).

Refusal to refer

Among health practitioners who refuse to refer their patients for abortion care, some have moral or religious grounds (conscientious objection), whereas others have reasons that are not conscience‐based, such as discomfort, stigma, or fear of repercussions.1,5 Regardless of reason or objection status, refusing to refer violates a range of professional codes of conduct (Box 1). There are also legal considerations; in many jurisdictions, referral is legally obligated if practitioners refuse to provide abortion care for conscience reasons.10 Yet in practice, referral by objectors is inconsistently carried out and rarely enforced.1

Refusal to refer is a well documented barrier to abortion.1,11 It harms patients by delaying care, which can increase costs and travel, constrain choice of abortion methods, and potentially lead to denial of care, with economic, educational, and emotional consequences.1,4,5,12

Unprofessional referral

Even among providers who do refer for abortion, referral practices can advertently or inadvertently obstruct access.3,5 Unprofessional referrals include rude, unfriendly, or judgemental communication, seeking to delay abortion access (eg, ordering unnecessary tests), or knowingly referring to a service that will not provide an abortion (eg, adoption clinic, pregnancy crisis centre, or objecting provider) — these practices have been documented across Australia3,4,5,6 and elsewhere.1 Such unprofessional referrals violate codes of conduct and medical guidance focused on respect and facilitating care, yet are rarely the focus of efforts to improve abortion access.

In practice, unprofessional referrals from health practitioners who refuse to participate in abortion can delay care, cause under‐ or misinformation, cause emotional distress to abortion seekers, and increase their reluctance to seek further abortion care.2,3 These impacts are similar to those of refusal to refer.

Minimum professional standards for abortion referral

In accordance with medical guidance and professional codes of conduct (Box 1), professional referral practices should encompass both how a referral is communicated and the information that is delivered. We propose that, at a minimum, an abortion referral must be (i) timely, (ii) communicated in a non‐judgemental manner (eg, without questioning the decision or punishing the patient for seeking abortion care), and (iii) be made to a high quality and willing provider who can provide abortion care or refer the patient onwards (eg, a general practitioner without a conscientious objection). Importantly, professional referral practices must comply with jurisdictional legal requirements. These requirements vary, with some allowing information provision only and others requiring referral. For example, in Victoria, an objecting provider is required to refer to someone else in the same profession who does not have an objection.5

To support professional referral practices, referral pathways for abortion care must be systematised so that all health practitioners have clear and accessible information about where to refer for high quality care,13 for example through state‐based hotlines such as 1800MyOptions in Victoria.

Person‐centred referral

A person‐centred referral moves beyond minimum professional standards to centre the needs and preferences of the abortion seeker (rather than the health practitioner). Person‐centred referrals are part of “care that is respectful of and responsive to people’s preferences, needs and values, and which empowers people to take charge of their own SRH [sexual and reproductive health]”.14 They support the pregnant person’s right to dignity and autonomy by facilitating access to timely, high quality abortion care in a friendly and empathic way. For example, a referring health practitioner could send a formal written referral with clinically relevant information about the patient to a willing practitioner or service, or can contact the clinician or service (including pathology or sonography, as required) to verify their availability. They centre supportive care, trust, autonomy and communication, which are key domains of person‐centred abortion care.2

What can be done to move health practitioners along the continuum towards person‐centred referral practices?

The importance of person‐centred referral can be reinforced at various levels across the health system.

Professional bodies have a critical role in articulating and enforcing professional standards and codes of conduct — with a focus on regulating medical professionalism rather than over‐regulating abortion. Medical guidelines should clearly articulate standards for professional abortion referral practices. Medical education should train future providers on person‐centred referral, including through values clarification approaches. Colleges and training pathways can provide practical training. This is particularly relevant in general practice, the discipline responsible for most referrals in Australia.13 Government regulators, such as the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra), have a responsibility to develop effective reporting and enforcement mechanisms for individuals who avoid their professional obligations for abortion referral. All of these actors should also ensure that clear referral pathways for abortion exist and are shared with health practitioners, to facilitate professional referral practices.13

Health service policies and management can ensure that all staff are aware of their professional and legal obligations to refer respectfully for abortion. They can support practitioners to recognise person‐centred referral as part of high quality care. Across the health system, person‐centred referral could become a measure of quality or performance. Quality improvement interventions can promote respectful referral practices grounded in empathy, a core principle of person‐centred care.14 Strategies to promote empathy can draw on evidence that abortion seekers fear being judged, are unsure about their options, and are worried about whether they will be able to access the time‐sensitive service.2,3,4,6 This type of information can be integrated into stigma‐reduction approaches such as values clarification workshops, which support health practitioners to consider their professional responsibilities towards abortion seekers.15

At the individual health practitioner level, anyone providing referrals can reflect on whether they are — intentionally or unintentionally — referring in a way that does not fit with person‐centred care principles. There may be a role for bystander interventions in which health practitioners who hear about unprofessional referrals can share resources about the harms of unprofessional referral and support colleagues to understand the minimum standards for abortion referral.

Conclusion

Unprofessional referral practices undermine equitable access to person‐centred abortion care. In this perspective article, we have argued the importance of encouraging all health practitioners, regardless of objector status, to move along the spectrum towards person‐centred referral. Importantly, the specifics of how to achieve this will vary depending on medical guidelines, legal context, and institutional environment. This is a call for professional bodies, regulators, medical colleges, medical education, and the health system to integrate guidance on professional abortion referral practices and ensure these standards are monitored and enforced.

Box 1 – Codes of conduct, professional guidance, and legal frameworks relevant to abortion referral practices in Australia

Referral‐specific principles:

Medical Board Ahpra Good medical practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia8

“Ensuring your personal views do not adversely affect the care of your patient or the referrals you make”

all providers should be “acting in your patients’ best interests when making referrals”

General good practice principles:

Medical Board Ahpra Good medical practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia8

“Facilitating coordination and continuity of care”

“Treating your patients with respect at all times”

“Respecting patients’ rights to make their own decisions”

“Avoiding expressing your personal beliefs to your patients in ways that exploit their vulnerability or are likely to cause them distress”

“Being courteous, respectful, compassionate and honest” with their patients

Conscientious objection to any health service:

Medical Board Ahpra Good medical practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia8

“Not using your objection to impede access to treatments that are legal”

“Not allowing your moral or religious views to deny patients access to medical care”

Conscientious objection to any health service:

AMA position statement on conscientious objection 2019 9

“Doctors have an ethical obligation to minimise disruption to patient care and must never use a conscientious objection to intentionally impede patients’ access to care.”

“Continue to treat the patient with dignity and respect, even if the doctor objects to the treatment or procedure the patient is seeking”

Conscientious objection to abortion specifically:

RANZCOG Clinical guideline for abortion care7

“Inform the woman how to access the closest provider of abortion services within a clinically reasonable time”

“Must not impose delay, distress or health consequences on a woman seeking an abortion”

Ahpra = Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency; AMA = Australian Medical Association; RANZCOG = Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Box 2 – Characteristics of abortion referral across the spectrum from refusal to person‐centred referral