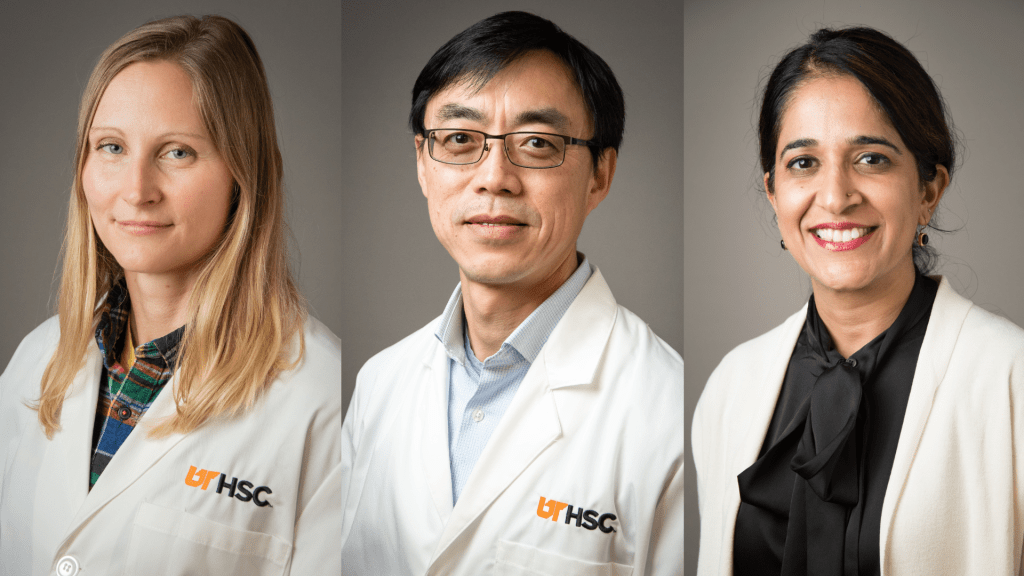

The research team is comprised of Dr. Megan Mulligan, Dr. Hao Chen, and Dr. Aman Bajwa.

The research team is comprised of Dr. Megan Mulligan, Dr. Hao Chen, and Dr. Aman Bajwa.

Why do some people experience memory loss in midlife while others stay sharp well into their 80s and 90s? A research team at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center has received a $3.1 million award from the National Institute on Aging to investigate this critical question.

The project is a joint effort of co-investigators from the College of Medicine: Megan Mulligan, PhD, an expert in genetics and complex traits; Hao Chen, PhD, who specializes in next-generation DNA sequencing; and Aman Bajwa, PhD, who brings expertise in mitochondrial biology and in-vitro brain cell models.

The team plans to uncover how genes and life experiences such as stress and environment combine to shape brain health over the lifespan. With this knowledge, the team hopes to create a roadmap that paves the way for earlier detection and interventions that could delay or prevent dementia.

At the heart of their work is a unique rodent model with a remarkable backstory. Developed through decades of careful breeding by their collaborator and consultant on the award, Eva Redei, PhD, Professor Emeritus at Northwestern University, the model consists of two nearly identical rat strains that differ at only about 4,000 spots in their genomes, compared to the millions of differences typically seen between humans. Despite these small differences, the two strains show striking contrasts in behavior. One is more prone to stress, depression, and substance use, and it also experiences premature memory decline in midlife. The other strain is more resilient.

“This reduced complexity model gives us a rare opportunity,” said Dr. Mulligan, associate professor in the Department of Genetics, Genomics, and Informatics. “Because the rats are so genetically similar, we can zero in on the specific variants that make one strain more vulnerable to oxidative stress and cognitive decline.”

Oxidative stress, a kind of cellular “wear and tear” that builds up naturally with age, is a prime suspect in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Dr. Bajwa, associate professor in the Department of Surgery, will provide expertise in mitochondrial function to help the team study how brain cells like neurons and astrocytes respond to this stress in controlled lab settings. Meanwhile, Dr. Chen, professor in the Department of Pharmacology, Addiction Science, and Toxicology, will use advanced sequencing to measure changes in DNA methylation, a type of “epigenetic switch” that can turn genes on or off and may explain long-lasting differences between the strains.

The researchers also want to understand how environment interacts with genes. In earlier work, the team showed that the vulnerable strain declines faster under repeated stress, but its memory improves when raised in a stimulating environment.

“By mapping both the genetic weak spots and the environmental factors that make things better or worse, we hope to identify mechanisms that could one day be targeted in people,” Dr. Chen explained. “The genes we find in rats may have human counterparts with real diagnostic or therapeutic potential.”

Dr. Mulligan emphasized that this project is especially timely. “Funding is tight, but there’s a national priority on aging and cognitive health, and our model stands out because it’s based on natural genetic variation, not genetic engineering. That makes it uniquely relevant to human aging.”

Related