In 1808 the idea of building the Erie Canal struck Thomas Jefferson as “little short of madness.” An Evanston author’s colorful new book shows why America’s original information highway was nothing short of genius.

“We had neither chart nor compass,” an inspired Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in 1835, “nor cared about the wind, nor felt the heaving of a billow, nor dreaded shipwreck, however fierce the tempest, in our adventurous navigation.”

Another A-lister of the times, Harriet Beecher Stowe, advised travelers to “take a good stock of both patience and clean towels.”

Perhaps more telling was the complaint of a seriously disappointed Norwegian traveler: “Ten hard long days. We were treated like swine.”

What were they talking about and why were their perspectives so wildly different? Travel on the Erie Canal was the topic. The myriad perspectives take up an entire book by Evanston author Laurie Lawlor.

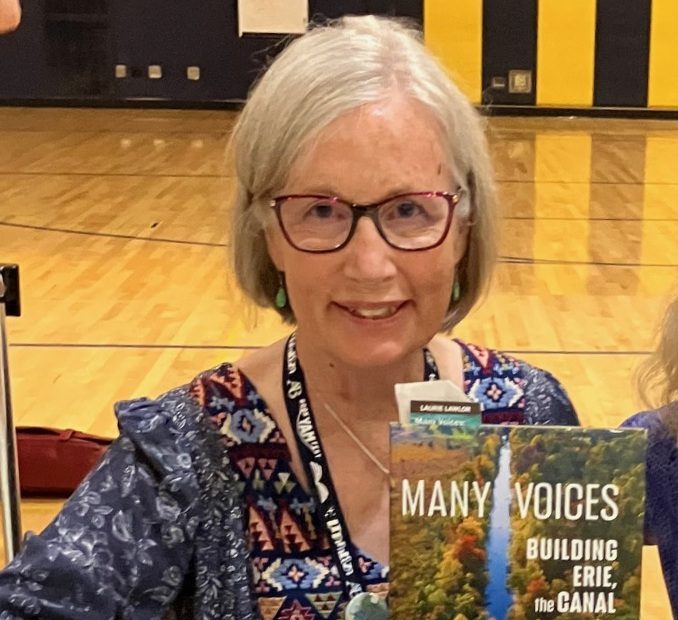

On the 200th anniversary of the canal’s completion, Lawlor tells the canal’s origin story in her 45th book (or maybe 49th; she’s not sure). Its title is Many Voices: Building Erie, the Canal that Changed America ($19.99. Holiday House. 352 pages), and it was released on Aug. 19. Hawthorne, Stowe and the disgruntled Norwegian are just three voices and, in Lawlor’s eyes, not the most important.

“Evanston, Chicago, Milwaukee and countless other Great Lakes cities benefited from the creation of the canal,” Lawlor told the RoundTable. How so? The canal “transported immigrants, cargo, finished goods and new ideas from the Atlantic Ocean and New York City’s harbor to America’s heartland.”

Award-winning author

Lawlor is an award-winning author of children’s books. Many Voices was recently named to Illinois Reads 2026, a list of books by Illinois authors chosen by the Illinois Reading Council. Other recognition includes Super Women: Six Scientists Who Changed the World, named an Outstanding Science Trade Book in 2018, and the picture book biography, Rachel Carson and her Book That Changed the World, which received the John Burroughs Riverby Award for Excellence in Nature Writing in 2012. (Yes, “changing the world” is clearly a favorite theme, which Lawlor not only writes about but, as an environmental activist, also acts on.)

A longtime Evanston resident, Lawlor and her husband of 50 years, Jack, have two adult children and four grandchildren. Granddaughter Vivian Beaudoin is credited in the book for helping Lawlor organize photo research last year as a seventh-grader.

Lawlor tells the story differently than other “history” books for ages 10 and up might. (As a proud member of the “and up” crowd, let me say that this book is so well written that it can hold the interest of many different readers.)

It’s also worth pointing out what Hawthorne didn’t say. Even in high-adventure mode, there was a good reason that “neither chart nor compass” were needed to navigate the canal. It was 40 feet wide, 4 feet deep and plied by slow-moving vessels towed by mules or horses sometimes led by 6-year-old girls. Passengers themselves could — and did — leave the boats to walk or “trot,” as Lawlor writes, on the towpaths. “Dreaded shipwrecks” driven by “fierce” tempests? Not to worry, Nat.

Lawlor carefully shows that such transportation was a much bigger deal then than it seems now, looking back from so long in the future. The barely 40-year-old country had survived two wars with England, but London had cut off trade with America after the Revolution. And the U.S. had badly neglected interstate commerce. Unimaginably poor roads and few-to-none water routes made doing business almost impossible.

The canal, generally touted as an “engineering marvel,” led to “immediate, booming trade. A resounding economic success,” Lawlor writes. It also had a “profound impact” on the “flow of new products and ideas — political, religious, economic and cultural.” So much so that Lawlor doesn’t hesitate to rank it right up there with the Internet as the “information highway” of the time. She also sees it as a technical achievement comparable to the moon landing.

Forgotten immigrants

But the focus of the book is on people, especially contributions of “untold thousands of men, women, and children” whose “stories were often purposely overlooked, or unrecorded or forgotten.” Many such people were “low-paid immigrants” without whom the canal would not have been possible. Lawlor doesn’t mention today’s immigrant issues but similarities are hard to miss.

Construction on the canal had begun with great patriotic fervor on July 4, 1817, and its grand opening was celebrated with similar fanfare eight years later on Oct. 26, 1825. New York Gov. Dewitt Clinton performed a “wedding of the waters” ceremony by pouring water from Lake Erie into New York Harbor. Ironically, he did so from the deck of a “packet” boat named the Seneca Chief. The unceremonious displacement of six Indigenous peoples over some 20 years, the Seneca among them, ultimately enabled the canal’s construction.

How is the book “different”? Lawlor tells much of the story in the words and experiences of people who made the canal happen and those who traveled the canal on “packet” boats, so-called because they sometimes carried mail and packages. She also lets those who stood against the canal have their say. Thomas Jefferson declared it “little short of madness” and essentially helped to kill the idea when it was first proposed in the early 1800s.

The book provides valuable background about why the canal was critical to enabling the young nation to grow into the America we know today.

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 more than doubled the lands under American control. A few visionary Americans, including President Jefferson, realized that “something had to be done to strengthen national unity in the sprawling, fast-growing country,” Lawlor writes. He suggested the still fledgling federal government take on “public improvements” and assigned Albert Gallatin the task. The imaginative and ambitious Gallatin proposed a large-scale, national system of roads and canals paid for by the federal government (think Interstate Highway System) and Lawlor indeed describes the plan as “something from the 21st Century.”

Even though Jefferson could envision potential value in the some 828,000 square miles of the Louisiana Purchase, Lawlor writes, his reaction to Gallatin’s plan, which affected far, far fewer miles, was anything but enthusiastic: “You talk of making a canal 350 miles through the wilderness,” he said. “This is little short of madness.”

Of course, Many Voices provides all the facts and figures we expect to find in any history, including a handy timeline, helpful index and the some 250 sources Lawlor tracked down in her research.

The book is full of remarkable stories. Incredibly, in the early 1800s, when the canal was first proposed and leading up to construction, the nation had no trained engineers. No European engineer would take on what was regarded as a highly risky assignment.

Spending his own money, Canvass White, 26, a self-taught surveyor and mathematician traveled to England and over the course of a year taught himself how to build canals, locks and aqueducts. He also found expert help to build one big, beautiful American canal. He returned home to launch America’s first superhighway. It was made of water.

The author will sign copies of Many Voices at 3 p.m. Saturday at The Book Stall, 811 Elm St., Winnetka.

Related Stories