Warning: This story includes graphic images of bodily injury.

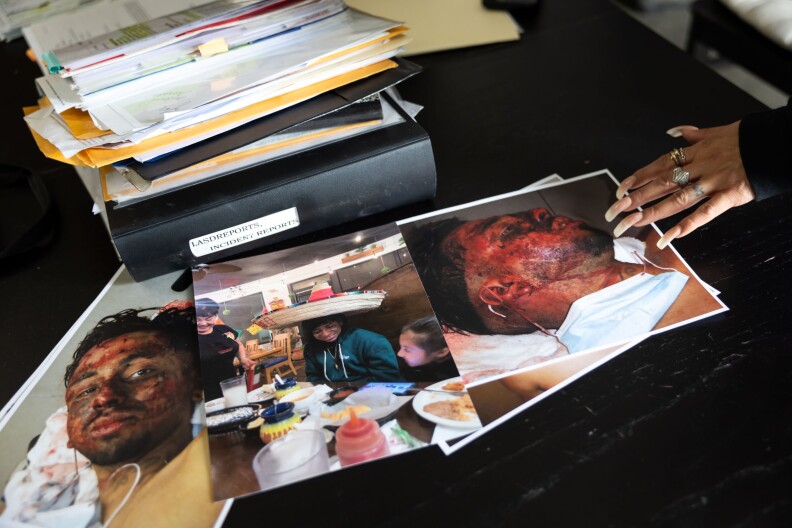

For years, Vanessa Perez has presented pictures of her son’s severely bloodied face at gatherings of Los Angeles County officials. At the Board of Supervisors, the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission and sheriff’s community meetings, Perez displays the disturbing images of her son, Joseph Perez, with his battered face on T-shirts, printouts and pictures on her phone.

With these images in hand, Perez continues to call attention to a July night nearly five years ago, when her son was severely beaten by a group of at least five L.A. County Sheriff’s deputies. Perez alleges the beating took place just hours after she informed the department that her son lived with mental illness and needed psychiatric help.

“At the time, I thought they were there to help,” Perez said. “What I know today is totally different.”

After the beating, a doctor closed up cuts on Perez’s scalp and face with 17 staples and 19 sutures, medical records show. Deputies alleged Perez was resisting arrest, attacked them and that they too were injured in the scuffle, according to partially redacted Sheriff’s Department records. He was charged with resisting arrest and assaulting deputies, and spent roughly two years incarcerated in L.A. County jail.

Vanessa Perez goes through photos of her son Joseph after his encounter with sheriff’s deputies.

Perez believes that her son was the victim of excessive force at the hands of deputies. The Sheriff’s Department has released some records explaining their actions that night, but more than a dozen pages are fully redacted and do not include any documentation of an internal investigation to determine if the deputies acted appropriately. With the help of a local civil rights attorney, Perez filed a lawsuit in January alleging her son was “violently confronted and unjustifiably detained” by the deputies. The complaint seeks unspecified damages.

Now, Perez’s case is at the center of a legal battle between the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission and the Sheriff’s Department. The commission plans to file a separate lawsuit seeking records relating to Perez and two other cases. The commission wants the full, unredacted use-of-force report and other records, including witness interviews, summaries, exhibits, body camera footage, text messages and photographs or video recordings for all three cases. But so far, the Sheriff’s Department has not supplied the information.

The Perez case shows how people living with severe mental illness can fall through the cracks in systems that are supposed to offer help, leading to criminalization, criminal justice reform advocates told LAist. It also demonstrates the difficulty many families face in seeking law enforcement accountability, especially if they don’t have an attorney. If the commission is successful in its demand for additional records, the Perez case could also have implications for accountability moving forward.

In an emailed statement, the Sheriff’s Department said it “remains committed to working in good faith to support oversight efforts while upholding the legal protections established to ensure the privacy and rights of all individuals involved.”

The department also said its asking a court to decide whether the commission’s interpretation of the law is accurate.

“Should the court agree with the [Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission], the materials will be disclosed,” the department said. “Without judicial guidance or legislative amendment, disclosing confidential peace officer records could expose the Department to serious legal consequences — including potential civil or criminal liability — and, most critically, could erode public trust.”

Robert Bonner, outgoing chair of the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission, told LAist that without being able to review full reports like this, commissioners “cannot provide effective and meaningful oversight of the Sheriff’s Department.”

“The kind of oversight, by the way, that the public, the voters, clearly said they want,” Bonner added.

What happened the night of the beating

Sheriff’s Department records obtained by LAist tell the partial narrative of an arrest attempt turned violent.

According to sheriff department records, at around 2 a.m. on July 27, 2020, two deputies arrived on scene in the neighborhood of East Valinda, near the City of Industry. They were responding to a call reporting a possible car burglary.

That’s where they allegedly found Joseph Perez tampering with a car and tried to detain him.

Deputies claimed Perez tried to run away. After they tried to detain him, Perez allegedly began kicking and punching one of the deputies. According to a Supervisor’s Use of Force report, the ensuing fight caused one of the deputies to “severely injure his leg.”

Ultimately, six deputies arrived on scene, with five delivering dozens of blows to Perez’s face, head and torso. Deputies alleged they commanded Perez to stop fighting several times.

Perez said he felt like the deputies ganged up on him unnecessarily.

According to the complaint filed by Perez’s attorney, deputies “put him face first on the ground and began to climb on his back.” The complaint further alleges that “at all times during this encounter… [Perez] believed that he was going to die.”

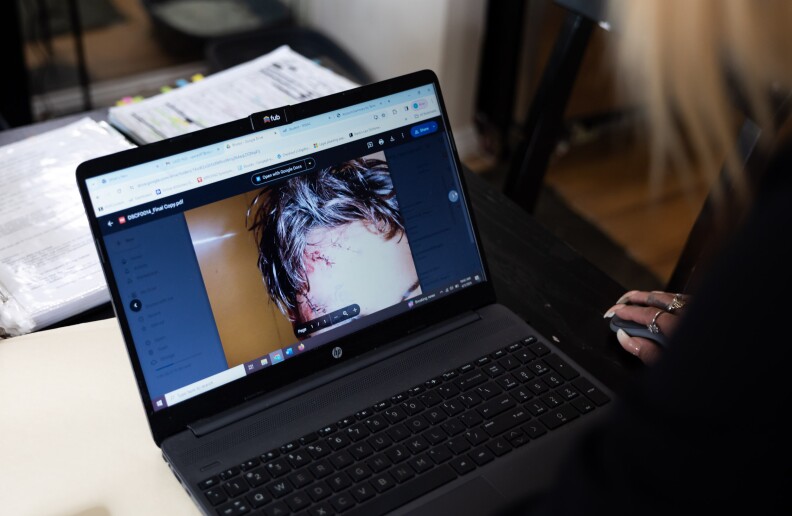

Vanessa Perez goes through video of her son Joseph after his encounter with sheriff’s deputies.

Vanessa Perez said her son was left with facial scars, ongoing pain and has suffered seizures lasting up to two minutes since the incident.

Perez questions why the arrest happened this way, especially since she claims she called the Industry sheriff’s station, where Joseph was being held just two days earlier for being under the influence of methamphetamine. Perez alleges she informed the station that her son lives with a serious mental illness and needed to be hospitalized in a psychiatric facility.

But hours later, Joseph was released anyway.

“There’s no way that those officers did not know who my son was,” Perez said.

Michele Infante, a criminal justice reform advocate formerly with the group Dignity and Power Now, said that after her extensive review of the case, she believes the deputies used excessive force.

She called the deputies’ actions “horrific.”

“Everything about this whole case is completely wrong,” said Infante, who now works as a private consultant and has presented the Perez case to the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission. “This case is not just about the Sheriff’s Department beating Joseph terribly the way that they did. It’s about mental health.”

Serious mental illness falls through the cracks

Vanessa Perez said Joseph, now 27, started to show signs of serious mental illness shortly after he was hit by a car when he was 12.

Before the accident, Perez said Joseph had plenty of friends and hung out at a skatepark near their home in West Covina.

After the accident, Perez said he became more and more isolated. Over the years, Perez said Joseph suffered multiple bouts of psychosis, forcing her to call for help from local mental health crisis teams. He was diagnosed with multiple serious mental illnesses, including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, Perez said.

Once Joseph turned 18, Perez said, the Department of Child and Family Services said that, due to multiple disturbances in the home, Joseph could no longer stay with her and her two minor daughters.

Perez said she had no choice but to file a restraining order on Joseph if she wanted to keep her other two children with her.

“It was the hardest decision I’ve ever had to make… And Joseph ended up on the streets,” Perez told LAist.

She said Joseph, who was unable to care for himself, would come to her home and bang on the doors, asking to come inside.

“And it broke me. It broke me to pieces. Trying to explain to him, ‘you can’t be here,’” she said.

Perez remembers looking for Joseph on the streets every night, trying to make sure he had a meal.

Just two weeks prior to the beating by sheriff’s deputies, Perez said her son was placed in a psychiatric ward. Just days later, he was back on the streets and attempted to light himself on fire, she said.

“I would have gave anything just for them to help me put him in a home,” Perez said.

But instead, he was released without access to supportive services, only to be arrested and incarcerated after the July 2020 incident.

Last year, thanks to the county’s Office of Diversion and Reentry, Joseph was living in supportive housing and trying to get his life back together.

Last September, sitting next to his mom at Magic Johnson Park in Willowbrook, Joseph said he was working toward getting permanent housing, a job and a driver’s license.

Vanessa and Joseph Perez.

(

Robert Garrova / LAist

)

As for the incident in 2020, Joseph, a soft spoken man of slight build, said he didn’t think he was treated fairly and hopes the deputies who beat him will be reprimanded.

“Because this is beyond what they should do,” he said. “Basically they just dog piled me and got on top of me and started hitting me on top of my skull… I was bleeding.”

‘Not set up to help them’

Criminal justice experts told LAist Perez’s case is indicative not only of the struggles vulnerable people living with mental illness face in getting the proper treatment, but also how difficult it is for families like his to pursue any recourse when they feel like law enforcement uses excessive force.

“People with significant mental health issues are both deeply vulnerable and also incapable, often, of responding to the commands of law enforcement,” said Eric Miller, a law professor at Loyola Law School. “And when they don’t, [law enforcement] then escalate the use of force into physical violence.”

Miller also regularly visits the county’s carceral facilities as a member of the Sybil Brand Commission, which is tasked with monitoring jail conditions. He said he checked in on Joseph when he was incarcerated at the request of Perez’s mother.

“If they are treated in this brutal manner and want to gain some measure of justice, the system, especially the oversight system, is not set up to help them,” Miller said.

Oversight bodies, like the Office of Inspector General and Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission, aren’t tasked with representing individuals. These oversight groups are typically addressing systemic issues like deputy gangs or jail conditions, Miller said.

Finding an attorney willing to represent someone in Joseph’s situation can prove very difficult, he added.

Joanna Schwartz, a professor of law at UCLA, said that in her research, it’s often only through a lawsuit that evidence is truly tested to see who was at fault in cases like this.

“Our law enforcement agencies are pretty uniformly miserable at capturing and making publicly available data about what their officers do,” Schwartz, author of the book Shielded: How the Police Became Untouchable, told LAist. “When there’s not a lawyer who has taken on the case and not a lawsuit that’s been filed, we have no idea how many people there are in his situation and in his mother’s situation.”

But thanks to Perez’s persistence in getting her son’s story in front of officials, a local civil rights attorney has recently taken up Joseph’s case.

Vanessa Perez goes through documents related to the case of her son Joseph’s encounter with sheriff’s deputies.

Jamon Hicks, a partner at Douglas Hicks Law and a current member of the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission, filed a complaint in January against the county alleging “serious and unreasonable force” at the hands of sheriff’s deputies.

“I’m really curious to know what it is that the police are saying he did to warrant that kind of force being used to where he looks like that,” Hicks said. “It is incredibly painful to look at [the photos of Joseph] and to wonder what could possibly have happened to justify that level of force.”

Hicks added that he will first have to convince a judge to allow the lawsuit to move forward since filing deadlines were missed years ago.

Why the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission plans to sue

By way of an official subpoena filed in March, the the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission demanded the Sheriff’s Department produce the full, unredacted use-of-force report package, including any body cam footage, witness interviews and text messages related to the Perez case.

The commission has also demanded records in two other incidents.

In the case of Emmett Brock, a teacher who was beaten by a sheriff’s deputy in a 7-Eleven parking lot, the commission is also seeking use-of-force reports, body-worn camera and bystander footage as well as witness statements. According to the subpoena, the deputy pleaded guilty in federal court to using unconstitutional force against Brock during the 2023 incident.

The commission is also seeking investigative reports and witness interviews in the case of Andres Guardado, a 23-year-old killed by a deputy in June 2020.

But so far, the commission has been unsuccessful in getting the additional records it requested.

In an emailed statement, Max Huntsman, L.A. County’s Inspector General who is tasked with promoting transparency and constitutional policing within the Sheriff’s Department, said the department’s custodian of records failed to appear in response to the commission’s subpoena, “which mirrored conduct from the Villanueva administration and was deeply troubling as such a failure to appear is not justified by the assertion of privileges as to some items subpoenaed.”

Huntsman added that the Sheriff’s Department “has always been strongly resistant to oversight.”

“I do not think it is likely that will change any time soon,” Huntsman said.

Commission chair is dismissed

Amid the commission’s efforts to enforce the subpoenas, the outgoing chair, Bonner, told his colleagues at their last meeting that Supervisor Kathryn Barger dismissed him “without so much as a phone call.”

In a letter dated April 18, County Executive Officer Edward Yen stated that Bonner’s term had expired.

“If you are interested in being considered for reappointment to the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission, please submit your resume within one week…” the letter states.

In an emailed statement, Barger said she appreciated Bonner’s service and contributions to the commission.

“I’m committed to broadening the diversity of voices and expertise represented on the Commission and believe it is important to provide others with the opportunity to serve,” she said. “My decision reflects my desire to continue cultivating public trust in the oversight process by introducing new perspectives that support the Commission’s vital work.”

At its most recent meeting, the commission said it still plans to take legal action demanding that the Sheriff’s Department supply in closed session the records it requested in the three cases.

“There are photos taken shortly after the arrest by Sheriff’s Department deputies that show that he was pretty severely beaten in the face,” Bonner, a retired U.S. District Court judge, told LAist in April. “The photos, by the way, are quite bloody. And his mother, who has appeared before us, has asked the commission a number of times — as the body that’s been given oversight over the Sheriff’s Department — to find out why there was no internal investigation.”

The commission, Bonner said, thinks it can receive and review the confidential reports in closed session.

“The Office of the County Counsel has fully supported the COC, as an advisory body to the Board, in its efforts to seek the information it needs to play a powerful oversight role on behalf of L.A. County citizens,” L.A. County Counsel said in a statement. “This includes assisting with a declaratory relief action that will hopefully bring judicial clarity to the commission’s ability to obtain the information it seeks and also drafting an ordinance to allow the COC to meet in closed session.”

Bonner said he believes the commission will eventually get the Perez records.

L.A. County residents, he said, gave the commission this oversight power when voters overwhelmingly passed Measure R in 2020, empowering the body with the authority to directly subpoena the department.

“This power is meaningless unless we can actually get access and review things like use of force reports and death review reports,” Bonner said.

During public comment at the oversight commission’s May 20 meeting, Vanessa Perez thanked commissioners for trying to move forward with the subpoenas.

“The people voted for this commission to have subpoena power so it could get to the bottom of cases like Joseph[‘s] and make sure deputies are held accountable for their actions,” Perez said. “I encourage you all to do whatever is necessary to get this information.”