Wildlife ecologist Chris Kirol has spent time of late surveying what used to be some of the last big tracts of sagebrush left in the Powder River Basin.

The veteran researcher has been looking for native vegetation like sagebrush, and also for the chalk-colored cylindrical droppings that are a telltale sign of where one of the biome’s icons, sage grouse, have been spending their time. On a Friday afternoon survey, Kirol took a call from WyoFile and described the landscape all around him, which had been completely transformed and for the worse.

“It’s almost completely dominated by cheatgrass and Japanese brome,” Kirol said, noting two noxious, nonnative grasses.

“I haven’t found a single sage grouse scat,” he added, “which is expected because there’s about five sagebrush left in this quarter-mile area.”

A researcher releases a sage grouse with a rump-mounted GPS tracker in the Powder River Basin. (Chris Kirol)

A researcher releases a sage grouse with a rump-mounted GPS tracker in the Powder River Basin. (Chris Kirol)

Kirol was walking through a burn scar from the nearly 180,000-acre House Draw Fire. The Johnson County blaze, which ripped through grassland and shrubland in August 2024, eliminated more than 100,000 acres of the “core” sage grouse habitat in the northeast region of Wyoming, where the birds dwell — more than a third of the best habitat in a region where the population was already struggling. There were 20 sage grouse breeding grounds — open areas known as leks — within the House Draw Fire’s perimeter.

“They were large leks,” Kirol said. “We know from years and years of research that this was one of the areas with the highest density of sage grouse left in northeast Wyoming.”

In the first year of post-fire monitoring, there were male sage grouse documented displaying at eight of the 20 leks — which is actually the same as during pre-fire surveys in 2024. But the tallies in the burn scar tumbled.

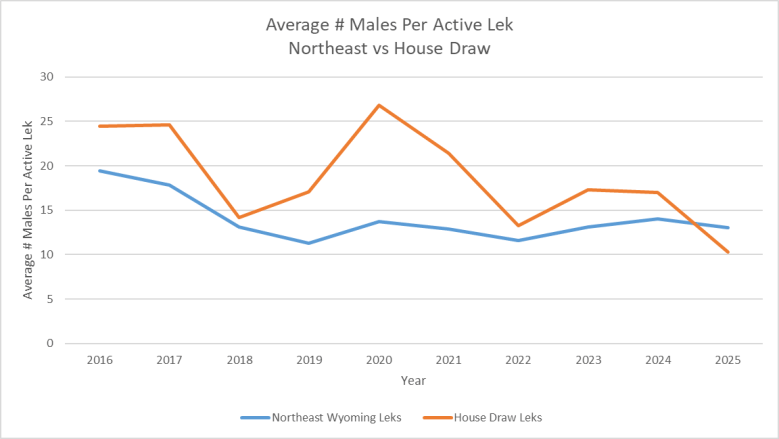

Sage grouse counts in northeast Wyoming, depicted here, have been steadily declining since the turn of the century and are not cycling in tandem with more robust western populations. (Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

Sage grouse counts in northeast Wyoming, depicted here, have been steadily declining since the turn of the century and are not cycling in tandem with more robust western populations. (Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

“Those leks were down 40%,” Wyoming Game and Fish Department sage grouse/sagebrush biologist Nyssa Whitford told WyoFile.

“Those birds took a hit, there’s no question about it,” she said. “If you see the House Draw Fire out there on the ground, you can see why it’s down. It burned hot, it burned fast, and in a lot of pockets there’s not much [sagebrush] left.”

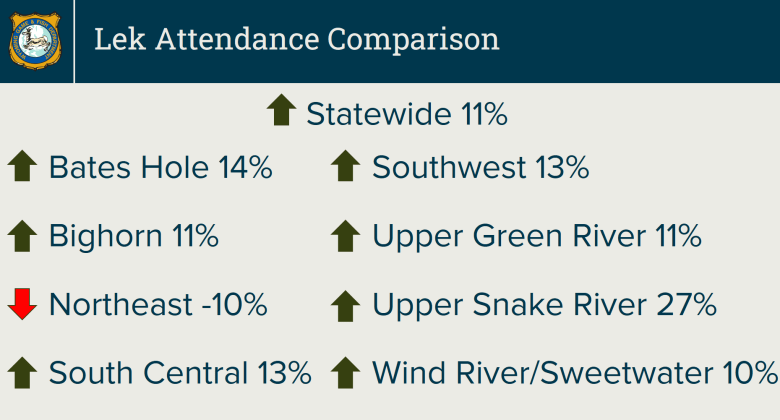

Adverse effects of the House Draw Fire help explain why the counts assessed at the 336 occupied sage grouse leks in northeast Wyoming fell by 10% in 2025 — a year when the naturally cyclic species otherwise did well across the Equality State.

Near the peak

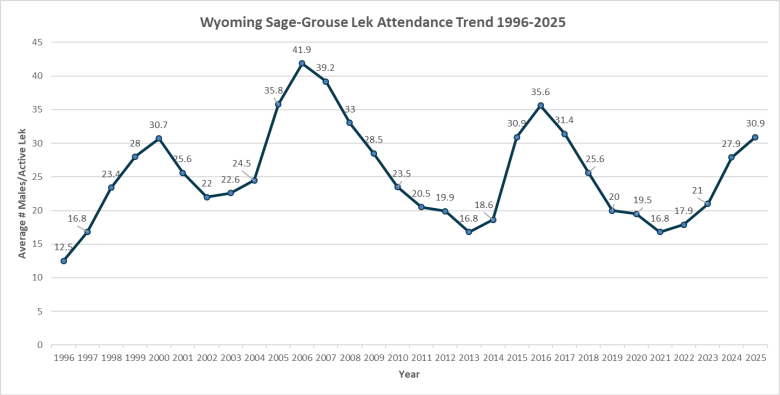

Hundreds of biologists, wardens and volunteers who fanned out across Wyoming’s sagebrush-steppe counted more than 30,000 male sage grouse strutting on 971 of the state’s known, occupied leks in the spring of 2025. That’s an average of 30.9 birds per active lek, which is a 10% increase over the 2024 counts and nearly a doubling of the population since the last low point in 2021.

Those swings are natural and part of basic sage grouse biology. Statewide in Wyoming, it takes about 9.6 years on average to complete a cycle, Whitford said.

“If I look back at the past data, I feel like this year is the peak,” Whitford said. “But we won’t know that until next year.”

(Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

(Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

Lek counts last crested in 2016, when there were 35.6 birds tallied per active lek, according to Game and Fish data. Before that, numbers topped out in 2006 when nearly 42 strutting males were documented on the average lek. If 2025 does go into the record books as the next peak, sage grouse abundance will have fallen nearly 36% since the 2006 peak.

Whitford pointed out that back in 1999, there was a lower peak: 30.7 birds per lek.

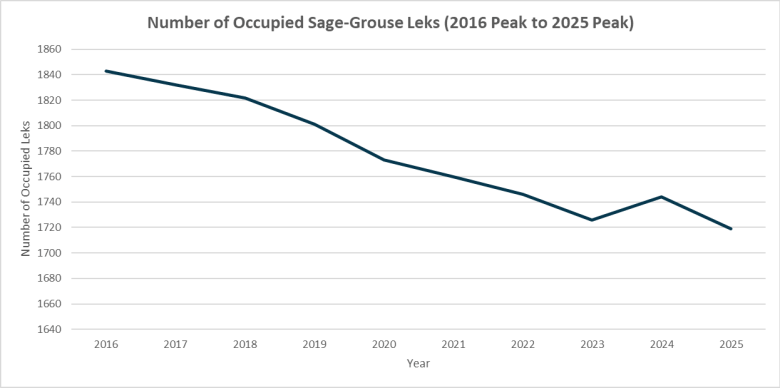

Other metrics suggest the state’s population remains in a long-term decline. The number of occupied leks statewide has fallen about 6.5%, from roughly 1,840 to 1,720, since the 2016 peak, Game and Fish data shows.

(Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

(Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

Sage grouse depend on a biome — sagebrush-steppe — that is disappearing and degrading at a rate of 1.3 million acres per year in western North America. The continued habitat loss explains why sage grouse numbers have fallen by an average of about 3% per year over the past half-century, according to a 2021 U.S. Geological Survey report. The chicken-sized bird’s persistent struggles have led to petitions calling for Endangered Species Act protections for more than three decades, but voluntary state plans have caused the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to avoid a listing, most recently in 2015.

Wyoming holds the biggest and best tracts of sage grouse habitat remaining in the world, and it possesses about 38% of the remaining birds. The 2025 lek counts surged by double-digit percentage points in almost the entire state.

Uniquely struggling

Northeast Wyoming, where counts fell by 10%, was the lone exception. While the House Draw Fire was a factor, the outlier datapoint could also be related to the natural cycle duration, which tends to run shorter in the region, Whitford said.

(Wyoming Game and Fish Deparment)

(Wyoming Game and Fish Deparment)

The number of northeast Wyoming males observed per active lek, 13, was also less than half the statewide average. Population performance in the area has consistently been the worst in Wyoming.

“Northeast Wyoming has always been at the edge of sage grouse range,” Whitford said. “The habitat is just not like the rest of the state. It tends to run a little drier and tends to convert to grassland very easily.”

Wyoming’s conservation plan for its northeastern sage grouse, last updated in 2014, details a long-term decline of the habitat and species. The “patch size” of sagebrush cover in the Powder River Basin decreased by more than 63% in a 40-year period, according to the report, falling from 820 acres to fewer than 300. Overall, sagebrush cover in the watershed also declined 6% as a portion of the landscape, from 41% to 35%.

Leks are being abandoned as the habitat has degraded and disappeared, long-term data show.

Out of 606 documented leks in the northeast region, only 178 — some 29% — were active during the 2024 breeding season, according to Wyoming’s latest statewide sage grouse report.

“Average male lek attendance in northeast Wyoming has decreased significantly over time, decreasing by more than half over the last 30 years,” wrote Game and Fish Wildlife Biologist Erika Peckham, who authored the section of the report.

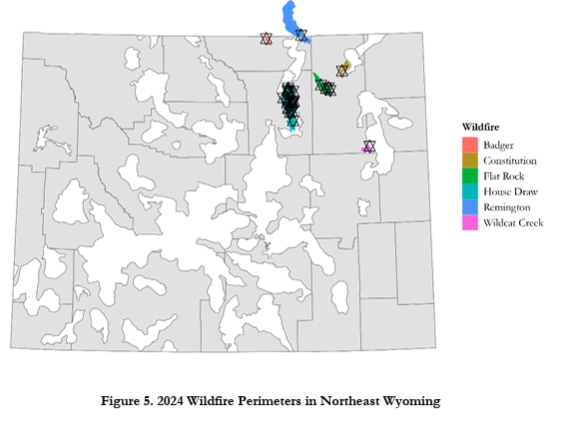

Wildfires burned over more than a third of all the sage grouse core area in northeast Wyoming in 2024. (Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

Wildfires burned over more than a third of all the sage grouse core area in northeast Wyoming in 2024. (Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

Northeastern Wyoming’s 2024 wildfires, especially the House Draw Fire, are all but guaranteed to exacerbate the declines. Although surveyors detected male sage grouse at 40% of the leks in the House Draw Fire scar during the 2025 lek counts, the large interior leks near where all the sagebrush burned up are likely to disappear completely.

“Females nest almost exclusively in sagebrush — 99% of the time,” said Kirol, the Sheridan-based sage grouse biologist. “So if the females aren’t showing up anymore … there’s going to be no [population] recruitment to those leks.”

A sage grouse chick in Powder River Basin coalbed methane country. (Chris Kirol)

A sage grouse chick in Powder River Basin coalbed methane country. (Chris Kirol)

Male grouse might continue to display on their lekking grounds for the rest of their lives, he said, and that might span another five years. But after that, they’ll die out.

“I expect a lot of the leks in the interior will blink out,” Kirol said. “I hope they don’t, but that’s what has been shown in the past.”

The smaller a sage grouse population becomes, the more susceptible it is to extirpation. That’s what recently occurred in North Dakota, where biologists counted zero strutting males for the first time in 2025.

Kirol has serious concerns for the future of northeast Wyoming’s sage grouse. The population, he said, has been in a steady, gradual decline for about two decades.

“The problem with northeast Wyoming is the birds are just constantly losing habitat, and they’re never gaining anything,” Kirol said. “I’m hopeful that we’ll still have birds here in 50 years, but we’re going to get to a point where, if the numbers get too low, then any natural event might wipe them out.”