Not only is the human brain naturally adaptive, but it’s also incredibly energy efficient.

Training a Generative AI model like OpenAI’s GPT-3, for example, is estimated to consume just under 1,300 megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity, as much power as used by 130 U.S. homes. The brain needs a fraction of that and requires no more energy than a common lightbulb to perform a comparable task. Data from the Johns Hopkins research suggests biocomputing could cut down AI energy consumption by “1 million to 10 billion times.”

“The development of large organoids for power-efficient neural networks could help with running complex deep learning models without significantly impacting climate change,” Ben Ward-Cherrier, a computational neuroscience researcher at the University of Bristol, told National Geographic.

How bioprocessers are already being used

It’s no longer an experimental pipedream either: a cottage industry of startups has raced to commercially build what some colloquially call a “living computer.”

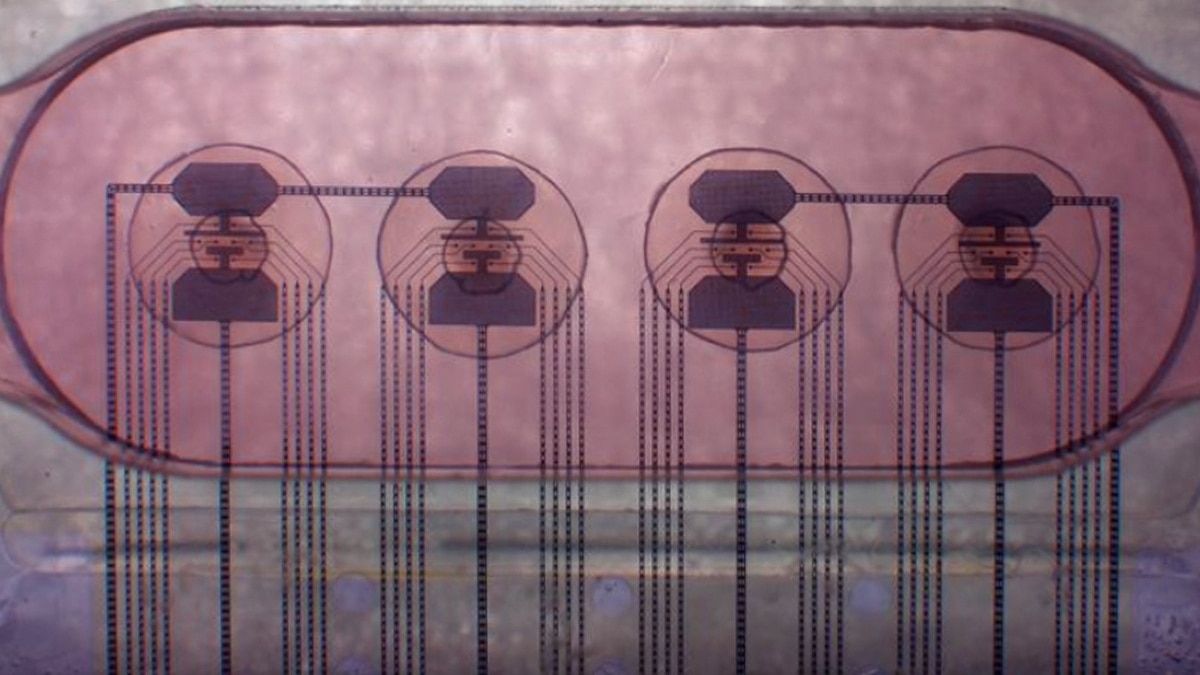

Swiss-based FinalSpark’s Neuroplatform, for example, lets anyone remotely run experiments on a cluster of organoids for $1,000 per month. Its facility incubates thousands of processing units, where each organoid is connected to eight electrodes plugged into a conventional computer. Using FinalSpark’s software, researchers can code programs to electrically stimulate the neurons, monitor their response, and expose them to the feel-good neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin to train them to perform computing tasks.