For pitchers, it was once like a $100 bill floating from the sky and landing in the palm of their hand. They would get a ball from the catcher, look it over, and there it was: a scuff mark. They didn’t put it there, but they sure knew what to do with it. It was found money, a supercharged sinker.

“We were watching the Ryne Sandberg game the other day,” said Kansas City Royals pitcher Seth Lugo, referring to a replay of a 1984 broadcast from Wrigley Field. “Sinkers in the dirt, foul balls, the umpire gives ’em to the catcher and they’re throwing ’em back to the pitcher. It wasn’t that long ago. No wonder they all had great sinkers – all the balls were scuffed!”

If Lugo gets a ball with a mark on it, he said, he’ll try to use it as long as he can. But the baseball gods almost never bestow such a gift anymore. As soon as a ball touches dirt, it’s tossed out of play before the next pitch.

It’s got to be a rule, right? To root out the trickery that crafty pitchers once mastered?

“No, no, it’s not automatic,” said Marvin Hudson, an MLB umpire since 1998. “If it hits the dirt, catchers will throw it out quicker than I would. If they hand it back to me, I look at it, and if it’s not scuffed, I’ll wipe it off and keep it in my ball bag. But players are a lot different than they were back when I first came in, as far as what type of ball they want. It’s kind of comical, to be honest with you.”

Watch a ballgame today – really watch it – and you’ll be amazed at how often the pitchers, catchers and umpires change the ball. Just how many does it take to get through a game? It’s like trying to guess how many jelly beans are in a jar. You can’t tell on TV, because the ball isn’t always on the screen. And you can’t tell in person unless you commit to looking solely at the ball the entire time.

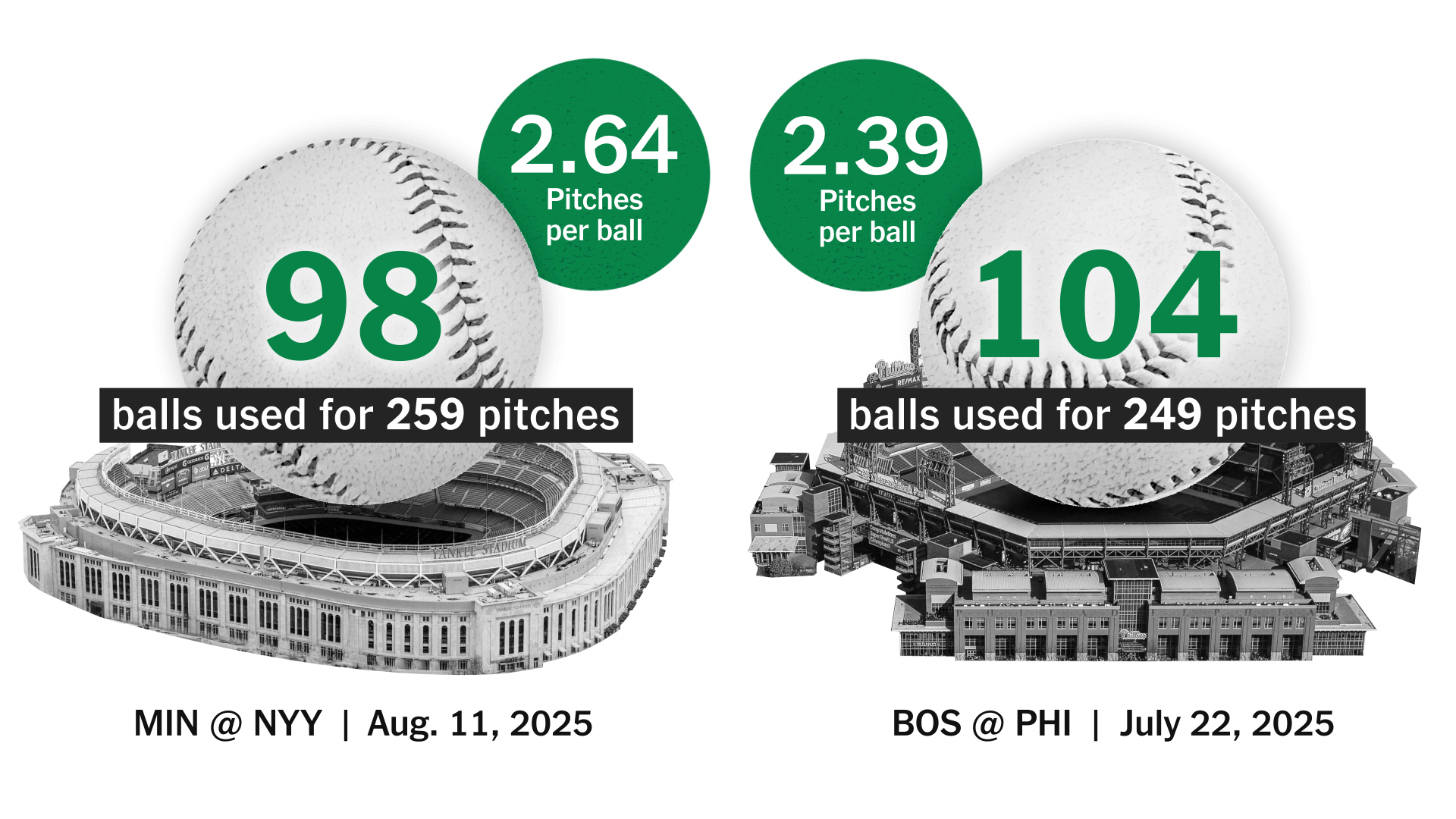

So that’s what I did. Twice this summer — on July 22 in Philadelphia and August 11 in the Bronx — I tracked the fate of every baseball used in the game.

The first lasted only one pitch, by the Phillies’ Cristopher Sánchez, who induced a ground out from Rob Refsnyder of the Boston Red Sox. As the Phillies made the play, plate umpire Edwin Jiménez reached into his ball bag and lobbed another ball to Sánchez.

The infielders tossing the out around the horn might as well have been pallbearers. This one’s useful life was over. Third baseman Otto Kemp tossed the ball to the home dugout, where an MLB authenticator labeled it with a hologram, bound for sale in a kiosk behind section 133 at Citizens Bank Park.

Both of the games were fairly ordinary: The Phillies beat the Red Sox, 4-1, and the Yankees beat the Minnesota Twins, 6-2. They were both night games, outdoors on grass, with no precipitation. Eleven pitchers combined to throw 508 pitches – 249 in Philly, 259 in New York – while using 202 different baseballs.

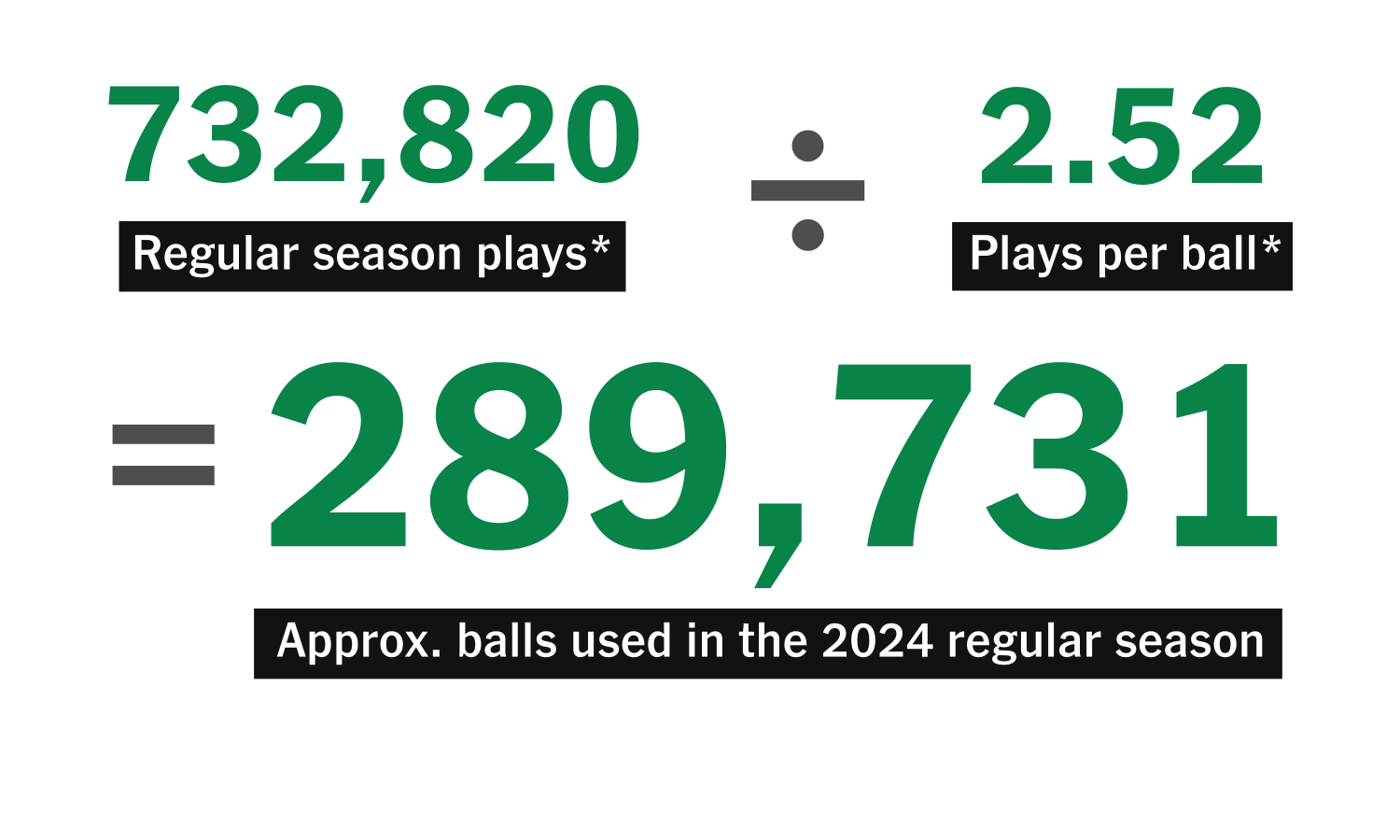

That comes out to 2.51 pitches per ball, right in line with MLB’s official data from the last few seasons: 2.60 in 2023, 2.52 in 2024 and 2.44 this season through August 20th.

Pitchers tend to know this without being told. Ask a pitcher to guess the lifespan of a baseball, and he’ll almost always nail the answer.

“I’d say the average life expectancy is less than three (pitches), slightly above two – and it didn’t used to be like that,” said Boston’s Liam Hendriks, 36, who started his pro career in the Gulf Coast League in 2007.

“We had a couple dozen balls for a GCL game. Any time a ball was in play and it was fielded, you’d use that ball unless you asked for a new one. And if you were a starting pitcher that wasn’t pitching that day, you had to chase down the foul balls.”

Things were similarly loose in the college game. Milwaukee Brewers manager Pat Murphy, who spent 22 years coaching Notre Dame and Arizona State through 2009, said umpires very rarely changed out the balls.

“I’d stick a road apple in there when the guy asked for balls – you did that sometimes, slip in an old BP ball just for fun,” Murphy said. “You knew the budgets were always tight. A big slice on the ball, they’d change it out. Other than that, no way.”

For decades, this is how it was in the major leagues, too. Oversight of the game’s foundational object was not a priority.

“When Don Mincher was our first baseman, if I had a guy up like Bubba Phillips, who was a notorious first-ball hitter, they’d throw the ball around the infield and Minch would come over to the mound and I’d say, ‘Give me the infield ball,’” said Hall of Famer Jim Kaat, who pitched from 1959 to 1983. “I’d give him the game ball and he’d throw it in the dugout. So the first ball I threw was the infield ball with all the grass stains on it.”

Coaches from that era would pass down the dark arts to the next generation. Mel Stottlemyre, a contemporary of Kaat’s, had pitched with Whitey Ford for the Yankees. Ford loved using scratched baseballs – he would apply it himself with a specially designed ring, or have the catcher, Elston Howard, subtly drag the ball across a metal buckle on his shin guards.

“Whitey was a master, and Mel was a master, too,” said David Cone, who pitched on staffs coached by Stottlemyre with the Mets and Yankees. “The trick he taught me was to keep the ball in your hand when you go down and grab the rosin bag, then touch the ball to the ground and you get a little dirt on it. You’d have a little sweat on the ball so the dirt would stick. He could make the ball dance and sink naturally with just a couple of pebbles of dirt.”

Cone, who pitched from 1986 to 2003, learned the perils of this about halfway through his career. One afternoon in 1995, pitching for the Toronto Blue Jays in Oakland, Cone got a ball with a scuff in the perfect spot: the middle of the leather, on the wide opening between the seams of the horseshoe.

He put the scuff on the left side and gripped it like a sinker, knowing the ball’s right side – now heavier than the left – would naturally shift away from the blemish. And it did, much more than he intended.

“It just went vroooom – shot up and hit Mark McGwire right in the helmet,” Cone said. “Sent him to the hospital and knocked him out of the All-Star Game. That’s when I said, ‘Oh s—, I’ve got to be a little more careful here.’ Scared the hell out of me. That’s when I stopped doing a lot of that.”

Cone’s awakening roughly coincided with a shift in attitude about the supply of baseballs for any given game. Until returning from the 1994-95 strike, when teams were eager to repair fan relations, MLB discouraged players from giving balls to fans. Memos posted in clubhouses warned that fans could be injured, but teams were also just stingy with the supply.

“They were counting every baseball and reusing things – and don’t take this in a bad light, but we weren’t pushed to make it a fan-friendly experience,” said Jamie Moyer, who pitched from 1986 to 2012. “Right now it’s fan-friendly. If you can give away all the balls, go ahead, give them all away!”

That’s the illusion, anyway.

Once the game starts, if a staffer down the foul lines tosses a ball into the crowd – or a player does it, as they do at the end of almost every half-inning – it’s OK. And if a player in the dugout snatches a foul ball and holds onto it, nobody’s going to take it from him.

Almost every other ball goes to the MLB authenticator, who sits by a little tabletop in the corner of (or adjacent to) the home dugout. Once each ball is logged and labeled, it is ready to be sold; prices at a recent Phillies game ranged from $39.99 for a ball pitched by the visitors (and not put in play) to $199.99 for an RBI double hit by a Phillie.

Some balls, however, are priceless. Sánchez was at his best on July 22, spinning the third complete game of his career. He was so efficient in the 1-2-3 ninth that he used the same ball for all 10 pitches: two balls, seven strikes and one line out. He kept it as a souvenir to be displayed back home in the Dominican Republic.

“I have a wall where I have all my accomplishments, my complete games, the All-Star Game accolades last year, and a Pitcher of the Month award, too,” Sánchez said through an interpreter. “It’s something that I use to motivate myself.

Many years ago, another Phillies pitcher wrote a children’s book from the perspective of a baseball. Tug McGraw, an impish lefty with a vivid imagination, created a character named “Lumpy” who dreams of the Hall of Fame but frets at his long odds.

“I’m still here in this box, right?” Lumpy says to himself before a game. “Maybe I won’t even get to play. I might end up in the batting cage. I might end up in some ump’s duffel bag as a surprise for his kid. Who knows?”

Little Lumpy – who winds up as a would-be grand slam that twists foul – was right to worry about his chances. Baseballs arrive at the ballpark in cases of 72 boxes, with each box holding a dozen balls. That’s 864 balls in a case. The Phillies estimate that their storage room holds somewhere between 36 and 48 such cases. If it’s four dozen, that means more than 40,000 baseballs waiting to be used.

MLB incorporates pitches (710,124 in ‘24) as well as pickoff attempts, disengagements, and pitch clock violations (combined 22,696 in ’24) in its definition of “plays” for this metric.

To be game-ready, though, the balls must be stored for two weeks, untouched, in a humidor set to 70 degrees at 54 percent relative humidity. Three hours before each game, clubhouse attendants apply a mixture of water and mud to 192 balls (16 dozen), which are then inspected by an MLB gameday compliance monitor. Fourteen dozen approved balls, or 168, must be available for each game.

The mud itself has a charming baseball backstory. It is named for Lena Blackburne, a light-hitting infielder from the 1910s, and still sifted from the same spot. Here’s how The New York Times’ Dan Barry once explained its origin:

While coaching third base for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1938, (Blackburne) heard an umpire complain about the struggle to prepare brand-new balls for use. Blackburne experimented with mud from a Delaware River tributary, not far from his New Jersey home, and found that it de-glossed the ball while mostly maintaining its whiteness.

Pitchers commonly added their own gripping agents – illegally, but effectively – until MLB banned so-called “sticky stuff” in 2021, with umpires checking pitchers’ hands and equipment. A year later, the league mandated humidor storage in every park and formalized the entire ball-preparation process.

After finding that rubbing techniques differed from team to team, the league sent a memo instructing attendants to “apply mud in uniform manner, ensuring the same mud-to-water ratio is applied to each ball” as they knead it into the leather for 30 seconds apiece.

The presence of gameday inspectors – one in the home clubhouse, one in the visiting clubhouse and a rover – was part of MLB’s response to the Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scandal, which The Athletic exposed in 2019. Gone are the days when a starting pitcher could persuade the clubhouse guys to rub the ball to his preferences.

“I’d go back and forth with Edgar,” said Moyer, referring to Edgar Martínez, his Seattle teammate and a hitting savant. “He wanted to see the seams, and the darker ball made it harder for him to see the seams. But I liked the darker ball. So we made a little adaptation: the days I pitched, I got the darker ball. And the days that I didn’t pitch, he got the lighter ball.”

These days, a laminated display in every humidor shows the three types of shades for a ball: light, target and dark. Each ball should fall between target and dark. A batch that’s too dark would never make it into a game.

“MLB follows a solid guideline,” said Tim Schmidt, a Phillies clubhouse attendant since 2022. “If a pitcher says, ‘I want them dark,’ we’re not doing dark. He might want them dark, but what about the pitcher on the other side? It’s got to be fair. So they keep it to a standard. Usually the rejects are pretty obvious.”

Each approved ball cannot be used for any other game; if it sees no action, it can be sold as “game-ready” or sent to the bullpen bag. Batting-practice balls are fresh from the box – pearls, they’re called. Easily thrown, easily seen.

Twice in the games we tracked, a batter hit a ball that touched only grass, not dirt, and was kept in play. Two other times, a catcher dropped the ball while transferring it from his glove to his bare hand; those balls also survived.

But basically, every ball that’s hit or pitched into the dirt will be removed, and every foul ball that doesn’t end up with a fan or a player goes right to the authenticator. And don’t even think about the old trick of the catcher short-hopping the ball to second base after the final warm-up toss.

“If that ball bounces to the ground when they send it down, everybody knows, ‘Hey, here comes a new one,’” umpire Ron Kulpa said. “Everybody’s dialed into that.”

The fresh ball pitchers get each inning might have a bit of dirt on it, though, depending on where it stops when the umpire rolls it out. And, yes, the umps are keenly aware that some fans pay special attention to that with “mound ball” wagers in the stands.

“You try to get it as close to the rubber as you can,” Hudson said. “We’ve had guys that’ll walk it out and just set it on top of the rubber for that inning, just so somebody wins. But it doesn’t go unnoticed. Fans play it. I’ve had friends come to spring training, they’ll sit there and bet amongst themselves about it, trying to see (if we) can get it to the mound. I’m like, ‘You guys gotta get a life!’”

We’ve all seen a pitcher get the umpire’s attention, hold the ball aloft and shake it lightly. It’s the universal signal for a new ball, followed by a soft toss to a bat boy and a fresh delivery from the ump.

Pitchers can reject a ball that doesn’t feel right – or, if it’s really wet, as a means to demand a rain delay. When Kaat played for the Yankees, he said, Lou Piniella would always assume that when a pitcher wanted a new ball, he was looking for high seams to throw a curve. That was helpful intel for Kaat.

“So every now and then I’d ask for a new ball – but I wouldn’t throw a curveball, I’d throw a fastball,” he said. “Just in case they were trying to guess, you know.”

For the Yankees’ Will Warren – who rejected two balls in a row before facing Ryan Fitzgerald in the third inning on Aug. 11 – the placement of the MLB logo stamp matters most.

“A lot of stuff I do, pitch-grip stuff, is based on where the logo is,” Warren said. “So if the printing’s off, I’ll throw that one out because it’s going to mess up what I do.”

Pitchers are more scientific than ever in designing the break and spin for each pitch. It makes sense, in that context, that they’d want the same type of ball every time, even if the rare pre-scuffed ball might enhance movement.

“With the spin rate and the way they’re releasing it, they can create that run,” Moyer said. “I just don’t know that they have the wherewithal to do that.”

Kansas City’s Michael Wacha, a 13-year veteran, said he’d rather know where a pitch is going than trust a scratch to do the work for him. So would the Minnesota Twins’ Joe Ryan, who said he’d rather use balls that are pre-tacked by the manufacturer, like the ones in Japan.

“The biggest problem now is sometimes you’ll get huge seams, sometimes they get tiny seams, sometimes you’ll get super-hard, tight balls, sometimes there are bumpy spots in it. I think when you’re trying to get this consistency that teams are driven on analytically, it’s like – if the baseball is different, that plays a big role.”

MLB has owned a stake in Rawlings, which manufactures the baseballs, since 2018. Home run rates spiked the next season to an all-time high 1.39 per game, leading to the widely held belief that the league had juiced its new product.

Home runs have since dropped to 1.16 per game, the same level as in 2016, and MLB has always denied making any deliberate changes to the properties of the ball. Even so, the league has always acknowledged that slight variations are inevitable with a product made from natural materials.

Those flaws mean that many balls never reach their intended purpose of participating in an actual game. It’s a rigorous process for aspiring major-league baseballs, as it is for the players themselves, and it often depends on luck.

“When you look at a pearl, it looks perfect, it looks great,” Schmidt said. “You rub mud in it and then you can see all the imperfections. They reject the ball because of the leather 99 percent of the time. Sometimes it’ll be too dark, too light, whatever. But most of the time it’s imperfection in the leather.”

Schmidt dabbed more Delaware River mud to his wet fingertips, spread the concoction on his palms and laughed.

“Bad leather,” he said, smiling. “It’s the cow.”