Listen to the episode on:

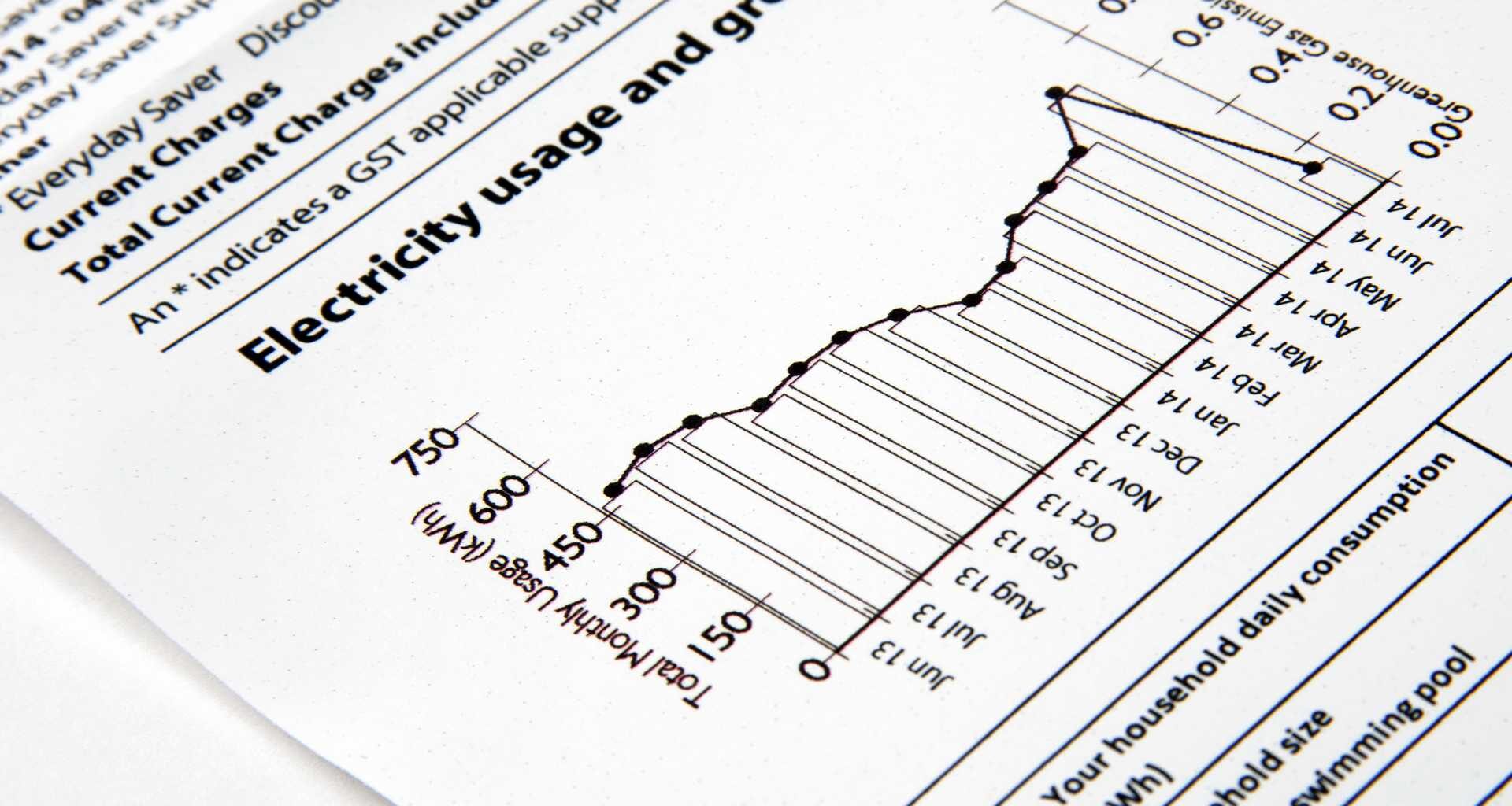

Eggs were the symbol of inflation in the last election. Now, as electricity bills spike, they are becoming a symbol for consumer frustration in 2026.

Americans are feeling the squeeze. Bills are up nearly 30% since 2021, outpacing inflation and straining household budgets. Eighty million Americans are struggling to pay, four in five feel powerless, and politicians are scrambling for someone to blame. On Truth Social, Trump points at renewables. On TikTok and Bluesky, users rage about data centers. Utilities blame extreme weather. Governors blame corporate utilities.

So who’s actually guilty? According to Charles Hua, the CEO of PowerLines, the real story is far more complicated: billions in spending for transmission and distribution systems without enough careful planning or oversight.

In this episode, we explore how rising bills are creating a political storm, how affordability is reshaping state campaigns, and what it would take to cut rates by 20% through smarter regulation and an emphasis on unlocking current grid capacity.

Credits: Co-hosted by Stephen Lacey, Jigar Shah, and Katherine Hamilton. Produced and edited by Stephen Lacey. Original music and engineering by Sean Marquand.

With resilience now a leading driver of grid investments, Latitude Media and The Ad Hoc Group are hosting the Power Resilience Forum in Houston, Texas on January 21-23, 2026 . Utilities, regulators, innovators, and investors will all be in the room — talking about how to keep the grid running in this new era of heatwaves, wildfires, and storms.

Want your clean energy brand to stand out in a crowded market? Work with Latitude Studios, our in-house agency that provides content creation and marketing services for brands at the frontier of the energy transition.

Transcript

Stephen Lacey: Man, Charles, I’m seeing you everywhere. You’re on a media blitz right now.

Charles Hua: Yeah. Well, electricity prices are the hottest topic in town. It started this year as largely just an energy story, but it’s become also a consumer and economic story, and now increasingly we’re seeing become a political story.

Stephen Lacey: Is electricity the new price of eggs, guys?

Jigar Shah: I don’t know. I guess you could make an omelet with an induction stove.

Katherine Hamilton: I do.

Stephen Lacey: Look, when they bring the electricity regulation nerds out on TV, on the morning shows, you know something is breaking through, right?

Charles Hua: They let anybody on these days.

Stephen Lacey: From Latitude Media, this is Open Circuit. This week, the price of eggs played a big role in America’s last election. Could the price of electricity determine the next? Utility bills are rising fast. They’re outpacing inflation, creating an affordability crisis, and they’re souring consumer sentiment. Everyone’s looking for someone to blame right now, renewables, data centers, climate disasters, Trump policies, but what is actually driving prices higher? Then, governors are desperate to land new data centers and factories, but voters are furious about skyrocketing bills. How will affordability shape American politics? And finally, if we wanted to cut bills by, say, 20% by the end of the decade, what would it actually take? A conversation with Charles Hua, PowerLines, is coming right up.

Hey, everybody. Welcome. I’m Stephen Lacey. I’m the executive editor of Latitude Media. As always, I’m joined by Katherine Hamilton and Jigar Shah. Katherine is the chair of 38 North Solutions. You were in Cornell last week. You were talking about bucking up the students at the engineering and business school. Did you succeed in your mission?

Katherine Hamilton: Well, it was awesome. First of all, I love Ithaca. It’s the best town. If it weren’t so hard to get to, I’d probably be there all the time. But it was wonderful. And it was actually at the Atkinson Center, which is a center that brings together all of the schools, so engineering and ag. And all of the different components of the university can work together in this center, and it means that people are super creative and interested. I really enjoyed it.

Stephen Lacey: Do you get a sense that students are freaked out by the current policy environment, or are they still feeling optimistic? What is the vibe check there?

Katherine Hamilton: I feel like the professors are more so because the funding being pulled away from universities. I think students are still really hopeful. And it was actually as inspiring for me as it could possibly be for them because they’re still moving ahead.

Stephen Lacey: Jigar’s with us. He is not lost in a casino roaming around. You made it out of RE+. Jigar’s a clean energy investor, of course. He’s the former director of DOE’s loan programs office. And I was asking you about what the mood was at RE+ sort of before the show really ramped up, but now that it’s over, has your assessment changed at all?

Jigar Shah: No. I think people came out of RE+ with a real fighting spirit. I think they recognize that the industry is being targeted, unfairly, of course, but they also recognize that, as we’re going to discuss with Charles, that rates have gone way up, and so their stuff is more cost-effective than ever because their price to compare has gone up. So they’re giving consumers hope and solutions. I think there were 5,000 more people at this year’s RE+ than last year’s, and so I think that that bodes well, I think, for the industry.

Stephen Lacey: Yeah. And I’ve seen a lot of coverage to that effect, that people were surprised at how optimistic a lot of folks at the conference were. Many of the reporters who swooped in expected to see an industry that was down and did not see that.

So Charles Hua is joining us. You might know him from his appearances all over the podcast world and morning TV shows. He is the executive director and founder of PowerLines, which is an organization that is working to modernize the arcane utility regulatory system and make it more transparent. Charles, how are you? Welcome.

Charles Hua: Doing well.

Stephen Lacey: What made you wake up one day and decide that utility regulation is the mountain you wanted to climb?

Charles Hua: I don’t know if it’s sort of an aha moment so much as, let’s call it, a bunch of scars, notably, that as I kept on digging into the public utility commissions and realized that these 200 people, they oversee at this point more than $200 billion a year in utility spending, that’s a lot of power concentrated in a fairly small group of folks for something as important as energy and electricity. Yet even in the energy space, not that many people can name their home state’s public utilities commissioners.

And from our point of view, we felt like there needed to be a more concerted effort organized specifically around making sure that the utility regulatory system of the present actually fulfills its purpose as initially constructed, which is to advance the public interest, to keep rates just and reasonable to protect and serve consumers. And I think we set that framework up over a hundred years ago; we are a far cry from that reality right now. And so there is an urgency behind this push to modernize a regulatory system, particularly at a moment where electricity demand is rising again and at a moment where the affordability crisis is becoming more and more severe.

Stephen Lacey: Somebody needs to create that deck of cards with the faces of utility regulators on them or something.

Jigar Shah: I don’t like it. I don’t like it. Although, I do name-check my regulators regularly on the podcast. They don’t appreciate it, but they’re still friends.

Charles Hua: Look, if we had baseball cards for regulators, I’m not sure what the batting average would be, but I’ll let folks opine on their own.

Jigar Shah: Well, it’d be terrible in Maryland. I think rates have gone up way faster in Maryland right now.

Who do we blame for rising prices?

Stephen Lacey: Well, so every moment of change needs a translator to take a messy complex system and explain why it matters to us, and that moment is right now. As we’ve said, electricity prices are rising incredibly fast. They’re spiking with all this swirl of forces around them. You’ve got this surge in data centers, an increase in extreme weather, the dominance of renewables, and an administration with a radically new approach to energy and to trade. And people just feel really bad about the economy right now, and so everyone is looking for someone to blame, and often placing blame based on their partisan priors. So we’re going to walk through the factors that are or are not contributing to electricity price increases, and more importantly, we’re going to look at how this is shaping politics and policy.

Katherine, to you right now as a scene-setter, how do you read the importance of the energy affordability story at the moment?

Katherine Hamilton: Oh, it’s absolutely crucial. I think it’s going to be a driving force in all the decisions that are going to be made in the next couple of years on state and local levels. And I would just say that data centers, I know we can’t get through an episode without saying data centers, but those are contributing to it, and that’s becoming a real pressure point.

What is interesting to me is that two weeks ago when we launched Common Charge to address affordability and reliability, so many people, from residential customers, to state governments, to PUCs, to small businesses, reached out, and their comments were, “How do we address affordability?” And it really feels like that is the big issue right now, and there’re going to be a lot of approaches to it, but I think it is absolutely front and center.

Stephen Lacey: Yeah. Jigar, you and I had a one-on-one conversation about this a few weeks ago, and so I know how important the affordability story is to your framework. And we’ve been talking about this for a long time, but tell me about where you think we are. Are we at crisis level right now?

Jigar Shah: We’ve been at crisis levels for a long time. The fact that people are paying attention now is useful, but I just want to make sure that people understand that we’ve been at crisis levels. Just a couple of anecdotes, right? This week, the electricity crisis in California and the Western power pool are 4 cents a kilowatt-hour. Southern California Edison charges 35 cents a kilowatt-hour and has a 10% rate increase going into effect next week. That means that for the first time ever, the generation cost of their bill is less than 10% of their bill.

The rest of it is grift, of whatever you want to call it, right? You can call it, people just didn’t take all of our warnings seriously for 15 years. You could call it, people wanted to run the grid exactly the way their grandfather did for so long that they just didn’t want to implement new technologies. You could call it a conspiracy against Richard Kauffman in New York who tried to put all this stuff in place with the REV back in 2012 and got ran out of town. You can call it whatever you want to call it. But since 2022, one of every six households in the United States now is late on at least one energy bill. That is a travesty in the wealthiest country in the world. And the fact that everyone is like, “We’re just doing hardening. We’re just relabeling stuff that we got wrong as wildfire expenses,” whatever crap that people are telling themselves, all I see is blatant incompetence.

Stephen Lacey: Blatant incompetence, grift, conspiracy. Charles, what’s your reaction? You’ve been tracking the numbers behind this story. Lay out the figures that you think tell the story best.

Charles Hua: Well, I’ll start with this figure, which is that four in five Americans feel powerless over these costs. I think there’s a couple reasons why that is. First, it changes so much month to month, unlike almost any other regular consumer expense that people pay. Second, there’s very little visibility and transparency into how all of it works. Again, unlike any other product, you don’t really know how much you’re paying for the product as you’re using it, and so that creates this feeling of frustration from folks where they see their bills spike. And we’re seeing this now blow up on TikTok, on Reddit, on Nextdoor, on Facebook groups, on social media. Even the Daily Mail is talking about electricity prices because people are really concerned. They feel overwhelmed, as Jigar pointed out.

Depending on how you define it, we define it as 80 million Americans that are struggling to pay their utility bills. That means that they’re trading off critical expenses like food education, health care, child care, just to keep their lights on, because obviously if you don’t pay your utility bills, you’ll get shut off from the system. So for a lot of folks that are struggling to make ends meet, which is the reality right now, they can’t shoulder an additional set of rate increases, but that’s exactly what’s happening right now.

So the other staggering statistic is that in the first half of 2025, we found that utility rate increase requests totaled $29 billion, which set a record for any year, and that’s just the first half of ’25. It was almost two and a half times the figure during the same two quarters of 2024. So if there’s no end in sight to this issue of rising utility bills, then we really need to ask ourselves whether the current utility regulatory system as presently constructed will be viable five years from now, if not even sooner.

Katherine Hamilton: And it feels like, Charles, that a lot of the answers to this that are being proposed are really addressing absolutely the wrong problems and won’t get us the results we need.

Stephen Lacey: Do you have some examples, Katherine, of where you think that the answers are misplaced?

Katherine Hamilton: Yeah, for example, some of the demand side programs that are being pulled back in California because of budget reasons, that’s not going to help. Some of the even federal programs that have been cut that are causing massive job losses in the same states that are increasing their rates, all of that is just going to continue to put upward pressure on prices.

Stephen Lacey: So we’re going to talk about solutions. I think we’re going to devote a significant part of this conversation to talk about what are the right solutions right now, but first I want to go to the blame game. So if you go over to Bluesky, you might see liberals attacking big tech companies for their AI data centers, or President Trump’s attacks on renewables. If you go over to Truth Social, you’ll see Trump attacking the Green New Scam. If you go to X, you might see Chris Wright sparring with Elon Musk over solar. So I want to walk through some of the factors and then circle around what is actually causing these price increases.

Firstly, let’s just talk about the role of renewables generally. The administration’s reflexively going after them, of course. What is their role?

Charles Hua: Look, I think a lot of the discourse has missed the fundamental reality, which is that the bulk of what’s driven up utility bills and electricity prices over the last, call it, five years is not really tied to generation so much as our grid infrastructure, the transmission and distribution infrastructure. In particular, in 2023, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab had this great study on retail electricity prices showing that distribution capital spend accounted for 44% of all utility capital spending, and that’s something that’s entirely under the jurisdiction of state public utility commissions. But we have very little transparency and visibility into the distribution system, so it’s not at all clear whether all of that spend has produced positive consumer outcomes.

I would be remiss not to mention some other factors, including the increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events, in the West, obviously wildfires playing a key role, in the Southeast and New England, storms, hurricanes, other extreme weather events that have really taken a toll on the grid and other energy infrastructure there, but also volatile fuel prices, and that’s largely driven by volatile gas prices, particularly following Russia-Ukraine was a key contributor to increases in both wholesale electricity prices and ultimately the utility bills that folks had to pay. So I think we need to have an honest conversation about what’s actually driving up bills so that any policy solutions that are put forth are meaningfully addressing the causes of bill increases.

And I should be clear, on a going-forward basis, everything that I just described in terms of why bills have gone up over the last five years, there might be a different set of reasons why bills go up in the next five years. There’s an unprecedented level of new power plant construction that’s currently being proposed by a bunch of utilities. I think from our point of view, there’s insufficient consideration of more efficient, quick, cheaper solutions that unlock electrons out of our existing grid more efficiently and cost-effectively. So what we’ve learned from the last five years may not be fully predictive of what will happen in the next five years, but the point being that the common through-line through all of this is that consumers don’t have a strong enough voice in the utility regulatory system.

Katherine Hamilton: And, Charles, doesn’t this all also lead to the fact that the utilities are given absolutely the wrong incentives? The incentives that they have now do not lead them to have outcomes for consumers that are in the public interest.

Charles Hua: That’s right. So the way that I describe it is there’s capital I incentives and lowercase I incentives. So for a utility on average, if you’re an investor on utility, what you’re responding to is what’s in your rate base, largely a function of capital spend; what your return on equity is; and I would say there’s now a third variable, which is AI hype, which is how muscular your press release can be in terms of being able to demonstrate that you’re meeting new demand. And that third piece I think is important because it introduces a wild card, sort of some level of irrationality into this, which we’ve had investors reach out, for instance, I think because there’s some valid concerns about whether we’re actually facing a bubble when it comes to things like utility stocks.

But then the lowercase I incentives I think really do matter. These are things like if a utility wants a social license to operate as a monopoly, it can’t just blow through rates indefinitely. There has to be some kind of ceiling, whether there’s a implicit or explicit ceiling. And it’s also a function of what questions regulators are asking. Are they doing their homework? Are they rolling up their sleeves? Are they willing to ask the tough questions about how utilities are spending an increasingly narrow set of dollars that can be wasted on gold-plating type projects? We need to be more disciplined about how we’re investing scarce capital in this moment where bills are going up so much, and I think that hopefully if we elevate the affordability concerns, then that’ll force and sharpen our collective decision-making in this space.

Jigar Shah: Yeah, they’re clearly not asking the right questions, right? That’s how we got into the mess that we’re in, and we’re not even close to getting out of the mess that we’re in, right? I just think that when you think about where we are right now just on the most simple things, like pull transformers, how long have we had smart breaker panels from Span.IO and Schneider Electric and all these other people, and folks are saying, “Oh, you need to add an electric vehicle? Well, instead of actually giving you a smart solution that costs $3,000, we’d like to rate base something that costs $12,000 and upgrade your pull transformer”? I think PG&E alone is going to rate base $7.5 billion in pull transformer upgrades over the next four years. When do you start saying to people that it is criminal for you not to use technology that’s 10 years old?

Stephen Lacey: So we have long talked about the misaligned incentives in utilities, again earn a rate of return based on how much infrastructure they build, and then that is what they’re pushed toward; they want to build more stuff. I guess the question I have is about… If most of these cost increases are coming because of investments in T&D infrastructure, how much of this is because utilities under-invested for decades and they’re catching up, and how much of it is new investment to accommodate some of these new challenges, whether it be accommodating electric vehicles, new industrial loads, or extreme weather? How do we separate those two things?

Charles Hua: Look, I think some of this, we don’t actually know for precise certainty exactly that quantitative breakdown because there’s just not enough data transparency into the distribution system and how exactly we have spent all that capital in terms of what’s a grid modernization project versus what’s a quote-unquote gold-plating project.

What I do think is important to call out here is that when it comes to things like grid planning, we do a terrible job across the bulk power system and the distribution system as it relates to our grid infrastructure, so whether it’s in integrated resource plans, we don’t sufficiently consider distributed energy resources or demand side solutions in IRPs, or whether it’s the fact that the majority of states don’t have any kind of distribution system planning process in place, not to mention, obviously, with transmission planning, we are way behind where we need to be in terms of inter-regional transmission planning, let alone even just implementing FERC Order 1920 well with regional transmission planning. So across the board, just from a planning standpoint, that’s creating a lot of challenges.

And the planning piece is really important because take something like a IRP, an integrated resource plan, some of the key inputs that flow into, call it, the end metric of cents per kilowatt-hour in terms of residential consumer impacts, are things like load forecasts, things like cost assumptions, and even just whether there’s probabilistic considerations at play. So I think there’s real questions around whether load forecasts are significantly inflated, and if a PUC doesn’t properly scrutinize that, as we’re seeing in PJM when the utility load forecasts are just stacked on top of each other, that creates some fairly staggering statistics that don’t necessarily pass the sniff test. In PJM, folks are saying that 30 out of 32 gigawatts, roughly 94%, of new load by the end of the decade is only data centers. I think that’s potentially highly suspect, and a lot of that flows from what PUCs across that network are or aren’t doing around scrutinizing utility IRP load forecasts.

And on the cost assumptions piece, one thing that’s important to note here is that we are in a highly volatile set of market conditions here where the utilities cost assumptions for, say, a new combined cycle gas turbine at the start of the IRP process may be significantly different from at the end of the IRP process. We’re seeing in some IRPs, for instance, estimates of $1,500 a kilowatt when that by now has significantly increased, and maybe a year from now it’ll be different. And so there are also questions about whether our regulatory system is nimble enough to be able to properly factor in these rapidly changing market conditions that ultimately impact consumer bills.

Katherine Hamilton: And, Charles, it feels like a lot of the modeling tools that utilities use have been outdated for years and they don’t take into consideration the customer side as a resource at all and they’re really pegged toward, “Let’s build another gas plant,” because that’s the capital expansion that they believe that they need based on their DSM, not the DSM potential, but the load growth that they see. But it also strikes me that the regulatory bodies are so underfunded and need staff and need to be able to hire their own consultants so that they can check the work of the utilities. Because right now a lot of what happens, the utility presents in their IRP all of their data that are basically in black boxes, and the regulatory body does not even have the resources to be able to check the work. So giving regulatory agencies some sort of additional support, additional resource, I feel like that’s one of the things we really have to focus on.

Charles Hua: I agree, and this is a smart investment for states. Every state’s in a different spot as it relates to both how they fund PUCs, whether it’s a fee on customers’ bills, or whether it’s through the state budget, and also just for the latter, how much budget they have, but I think this is really important.

Just to give you an example, in North Carolina, the ratio of… So the annual revenues of Duke is approximately 29 billion, and the annual budget for the North Carolina PUC is around 10 million. And of course, that’s not apples-to-apples comparison, but just as a sense of scale, that’s about a 3000-to-1 ratio in terms of the PUC’s capacity and the body that they’re supposed to regulate. Not to mention that these PUCs, they don’t just regulate the investor-owned electric utilities; they also regulate gas, telecommunications, water, and other utilities. So they’ve got their plates full. They’ve had their plates full even before this load growth and affordability environment, even before the proliferation of distributed generation resources. And so now in this moment, when you stack on top all of those, plus the pressures that they’re facing from their governors who appoint them or from the electorate that elects them, it creates this really messy storm where folks frankly feel overwhelmed, and I think that’s why we’re seeing a lot of the negative consequences of a under-invested-in regulatory system.

Jigar Shah: My sense is the frame is off though, Charles. Having spent so much time with all these regulators the last four years, I don’t think we’re ever going to educate them into Nirvana. So the big challenge that we have is that the solutions to the problems that we’re facing right now are not acceptable to all of the parties around the table. When you think about building a new natural gas plant, what that means is that you’re putting more electrons through the bulk power systems, through transmission lines, into distribution grids to meet peak demand. That is what that means. The same thing’s true if you build a new nuclear plant or a large geothermal facility, or for that matter, a lot of large wind and solar projects that have to be transported places.

The entire concept behind the REV was that you look at a distribution circuit and you say, “These 50 hours are the problem. How about we shift the load of the 50 hours,” which is what we did in the BQDM substation upgrade pilot back in 2012, “and how about we do that at scale?” We still are fighting that battle. If you talk to people at the local level in Maryland or in California, which has wholesale rejected this concept completely, it is not acceptable to choose that answer. It is not politically acceptable. The governors don’t understand it. Certainly the Truth Social post from Trump and the Twitter post from Chris Wright don’t allow it. And so what are you to do as a regulator? It doesn’t matter how much education you receive, the solutions to the problem are never increasing the capacity utilization of the existing transmission and distribution grid we’ve already paid for. That is not an acceptable answer. We can pilot it, “100%, let’s do a pilot,” but you are not allowed for that to be the mainstream way that you actually manage the grid. And so until that culture shift occurs, I don’t see how any of this gets better.

Katherine Hamilton: So, Jigar, you’re saying that PUCs will never change, but part of what PowerLines is trying to do, based on what I’ve read, Charles, and listened to you on all these podcasts, is you’re trying to get people involved and engaged and doing just that, in educating and in engaging with PUCs. So a big question I have is, is that working, and how is it working? Are you seeing some of what we’re talking about starting to get embedded into PUCs through better engagement?

Charles Hua: One of the manifestations, I think, of just how consumers are engaged is the fact that we are seeing an unprecedented level of engagement on this issue from governors, congressional offices, mayors, state legislators. Across the board, elected officials and political candidates are feeling some kind of pressure to be talking about this. So just to put some concrete examples, at the gubernatorial level, we’re seeing anybody from Republicans like Governor Cox in Utah call for a rejection of a 30% proposed rate increase in Utah, got it down to 4.5%; we’re seeing folks like Governor Shapiro in Pennsylvania sue PJM and impose market reforms; we’re seeing folks like Governor Healey talk about the need to have a more consumer-centric approach at the PUC. Across Democrats, Republicans, and independents, we’re seeing more and more engagement. At the congressional level, folks like Congressman Riley in New York, they’re actually intervening in rate cases, which is something that isn’t quite common.

But the reason why this is happening is because folks are hearing from their constituents, from members of the public, from residential energy consumers that this is something that’s a concern to them. And I think the question is, as this becomes more and more of a political issue, how can that be channeled in terms of that public visibility into a productive force for reforms? I think it’s important to call out that in 40 states, approximately, governors are the ones that are appointing PUC commissioners, and in 10 states they’re elected.

And historically, a lot of governors don’t put that much thought into their PUC appointments. They have to make hundreds of appointments to various offices and roles. I’ve heard governors admit that they were presented with sort of a couple finalists and they picked who sounded the best during the final round interview. Now, I’m not saying that’s true for every single governor, but I think having more of a thoughtful, intentional approach to who, from a personnel standpoint, a governor puts forth onto these commissions in terms of a more consumer-oriented regulator is critical, and I think it forces better decision-making by elevating affordability as an issue.

Just to talk about this a little bit more, the way that we sense what’s happening is that governors historically have viewed economic development as their primary responsibility, ribbon cuttings, jobs, investment. They haven’t necessarily viewed electricity affordability as something in that vein because it hasn’t necessarily been that salient or public or visible of an issue. But the problem there is that that’s led a lot of policymakers, including governors, to view economic development and affordability as trade-offs, which is, “Okay, if we’re going to power new data centers or manufacturing, we’re just going to have to accept that the only way to do that is by building new power plants that drive up bills.”

I think the opportunity set here is if we can get governors and other electeds to consider economic development and affordability in tandem and in parallel as tier one concerns, then the only path forward to achieving both is by getting more out of our existing grid by unlocking more electrons out of the grid infrastructure that we’ve built through all of the things that you all have certainly talked about for years around distributed energy resources, energy efficiency, grid-enhancing technologies, virtual power plants, and any other assortment of solutions that can unlock more juice now at a more cost-effective rate than building new infrastructure.

Jigar Shah: But I don’t understand how what you’re suggesting will work, Charles. You and I both know who those regulators are. I know who the regulators in Massachusetts are. They’re amazing. Same thing’s true in Maryland. And same thing’s true in New York. They have no permission structure whatsoever to approve the technologies that you just suggested. Look at Rory in New York. There is not a person that has talked more about grid-enhancing technologies and VPPs than Rory without doing anything about it. And it’s not because he’s the chair of the Public Service Commission. And it’s not that he’s against it. NYSERDA is not against it. They’re the ones who did the REV in 2012, but they clearly don’t have permission from the governor. And then when you talk to the governor of New York, she’s never going to become an expert in all of these issues that you just rattled off. So at some point, she just wants one of her political advisors to say, “Yeah, it’s acceptable to run a grid using those technologies.” And those political advisors are saying, “We’re not experts in electricity either.”

So the question is, where does that permission structure come in? And what I would postulate to you is in the past, it came from environmental groups, but those environmental groups are busy trying to shut down coal plants. They’re not promoting the technologies that you just talked about. They’re still saying, “How do we shut down coal plants and not build new gas plants?” They’re not for stuff. They’re against stuff. And so I think we’re just in a place where we think that the safe route is to educate public service commissioners. And I love the public service commissioners that I’ve met. I think they’re amazing, they’re trying their best, but I think that we look past the fact that they don’t have permission to do what you’re suggesting.

Charles Hua: Oh, I totally agree. And I think that what I would suggest is really needed in this moment is a very strong consumer voice. And I don’t just mean members of the public. I mean small businesses, I mean large commercial customers, I mean the data centers, I mean industrial plants. All of those customers have a key voice, and they all also want things like grid-enhancing technologies. I would argue that they’re not leveraging their voice as customers forcefully enough to push for some of those.

The other thing that I would say is I totally agree, I don’t think this is something that any one stakeholder in the regulatory system can unilaterally fix. In some instances, we actually may need new legislative action from state legislators, if anything, to create a political permission structure for PUCs to act more boldly. And the challenges there have been that state legislators historically haven’t felt particularly incentivized to stick their necks out and introduce and pass meaningful utility regulatory reform legislation, but we’re in a new reality, which is a load growth and affordability-constrained environment where state legislators are also starting to pay attention to this in ways that they haven’t before. And Congress has a role to play, too, because the lack of effective state-federal structures that synergistically make sure that the system actually works across our various silos has created a lot of problems. And I think increasing congressional engagement to smooth things out at the RTO levels, for instance, can be quite helpful.

Stephen Lacey: Yeah, so where else are we seeing blame, and is it warranted?

Katherine Hamilton: Yeah, so Heatmap did a really interesting poll across the US that found that Americans look beyond national politics, so this is regardless of what part of the political spectrum they’re on, they say that rising energy demand, their local utility and state government are all to blame for rising energy prices. So that’s what they’re looking at. They also say that they blame extreme weather and the oil and gas industry for rising prices. I find this very interesting because it doesn’t matter what side of the political spectrum they’re on, they’re all looking at a lot of the same things we’re talking about right here.

Charles Hua: Yeah. I think one of the interesting things about the Heatmap poll is that the one thing that both the most people agreed on and had the most bipartisan consensus was that people didn’t feel like their state government did enough to tackle this issue of rising utility bills. I think folks are actually quite sophisticated. They may not be able to name their public utilities commission, but they understand that their elected officials have something to do with this. They just don’t necessarily know who to point their attention to. I think from our point of view, they need to point their attention to governors, state legislators, mayors, Congress, everybody, because everybody does have an important role to play, and having some level of responsibility illuminated across those different stakeholders is key.

That also resonated with some of the results that we found in our poll, which did find that for every single question that we asked, the difference between Democrats and Republicans did not exceed more than three percentage points, which is the fact that people just feel like they’re not being looked out for in terms of their consumer interests by the utility regulatory system and they want action. And so part of what we’re trying to do with PowerLines here is to create a vehicle by which those folks can actually meaningfully channel all of that frustration into a productive outlet, and the off-takers of that energy, be it the political candidates, be it the sitting policymakers, actually have a substantive affordability-centered, utility regulatory action plan going forward.

Jigar Shah: The one other area, which we talked about last week but just to reiterate here, is that it is only a matter of time before the blame is going to squarely sit on the utilities’ shoulders, and the politicians will put it on their shoulders. And when that happens, this game becomes way more complicated. So part of the thing that I worry about is that the utilities are continuing to think they’re going to skate right now, and as soon as all of the blame is being put on their shoulders, I think this entire thing becomes exponentially more difficult to solve.

The politics of electricity prices intensify

Stephen Lacey: All right, so let’s take Jigar’s point and talk about how utilities may face consequences and where this is going to influence politics. I made a comment earlier about the price of eggs deciding the last presidential election, and it was kind of true, right? Eggs were seen as a stand-in for inflation across the economy. And we saw this little boost of optimism when Trump was first elected, but consumer sentiment today is worse than ever, according to some of the leading surveys, and suddenly it’s electricity, not eggs, that is the thing that people are focused on.

So we’ve established the nuances to what’s driving prices. Let’s talk about how this is going to affect decision-making. And to Jigar’s point that he just made, let’s start with utilities. I actually thought your point last week, Jigar, was something that I really agree with, which is that Trump and other politicians are going to lay blame squarely on utilities, and goodness knows what Trump will actually do when he focuses his attention on them. But, Charles, how do you think utilities will shoulder some of this blame, and what do you think the consequences will be?

Charles Hua: Look, I think some of this is really unpredictable. I think to Jigar’s point, there is a high degree of variance here in terms of the possible path forward. I think in general, the sort of blame game has been more along party lines or on generation resources and less on specific actors, although even that’s changing, like in the New Jersey governor’s race. I think that’s perhaps the earliest and deepest preview of what the politics of this could look like, where the general consensus among the Republican challenger is that it’s largely an anti-incumbent issue where the incumbents in power didn’t do anything while they were in power. And the Democrats in that race are blaming PJM, which in a way is a different incumbent in power. So in this moment of economic populism and concern about pocketbook issues, I think the general concern would be against incumbents. So when you’re a monopoly utility, I think you’re in a very potentially vulnerable situation if you don’t figure out a way to quickly tackle this affordability challenge seriously.

And we’ve talked about some of the solutions that are available right now at folks’ disposal when it comes to the specific technologies, but I would put a plug-in for other meaningful reforms, including things around transparency. It goes back to the fact that four in five Americans feel powerless over these costs, in part because there’s so little transparency and accessibility into how any of this works. And so when you’re one of those Americans that feels concerned, but you have no idea who to even call, or that there are three or five public utility commissioners in your state that actually set those final electricity rates, then I think that creates a greater risk and a wild card where the politicization of this becomes unproductive.

Where we come at this from is that we need more visibility and public engagement and engagement from governors and elected officials so that there’s a heightened degree of discipline in all of these decisions going forward, and we’re not wasting limited consumer dollars on investments that don’t actually benefit the interests of consumers.

Katherine Hamilton: Whether or not you want it to be political, there are two gubernatorial races this year. It’s an off year, except for New Jersey and the Commonwealth of Virginia, where I live. And you mentioned New Jersey, and Mikie Sherrill is running as the Democrat, Jack Ciattarelli is running as the Republican. And what is the utility doing? The utility that just completed a 17% rate hike, PSE&G, is blaming PJM. And so the utility has been asked, it’s been very much front and center, is this rate increase… As it should be. It’s a huge deal for the people in New Jersey, and now it’s become quite political. And in Virginia there have been a lot of discussions also about energy, where Abigail Spanberger is the Democrat now. It’s a Republican governor now, and they’re not allowed to run again. So the shift is more about an open field for whether it’s a Democrat or Republican, and the incumbency would be a Republican, so maybe people are looking at that a little differently.

But Axios had a roundtable where they brought people together, and energy costs have become this huge policy issue. Even the Virginia Department of Energy director said… He’s been involved in 10 election cycles in 15 years, and he said, “This is the first time I’ve seen energy as part of the conversation at all during election season,” which is something we’ve been trying to get people to talk about, and now they’re talking about it very negatively. And I know in Culpeper, where I live, all of the signs are anti-data center. And I will tell you the data center issue is completely linked in everybody’s mind to rates going up.

Charles Hua: And I’d be remiss not to mention that there’s a third election this year, the Georgia Public Service Commission election. It’s the only statewide election in Georgia where they had a primary and voter turnout was 3%. People don’t know that these public service commissions exist, and that’s a state where utility bills have increased 33% over the last two years.

And so this is a pretty unique moment in 2025 where the three prominent statewide races, New Jersey, Virginia, Georgia, the top issue is electricity prices. And I think as we’re seeing more and more signaling that this will become a top political issue in the 2026 midterm elections, I think folks of all political stripes are going to be paying very close attention to what happens this year to inform how they view the political stakes in 2026 as it relates to this issue of electricity prices. And I think part of why this issue is so salient is that it hasn’t been as tapped as a political issue relative to other things like healthcare or student tuition or childcare and things like that. So I think this makes for a very interesting political storm to come if we don’t figure out how to make this system work for consumers.

Jigar Shah: Right. But the way this always works is… I get the transparency argument, but the way this always works is people want to contract for America. They want to know exactly what are the top five things that you can do to reduce electricity rates. They don’t want to read all the filings themselves and be actually educated on WhatsApp or on Nextdoor or whatever. They want someone in a position of authority to say, “Here’s my five-point plan for how I’m going to get rates down,” and they want that memorized and they want that repeated every single time that person gets on stage. And I think that that, to me, is the part that’s missing right now.

Stephen Lacey: Yeah. So, Charles, who is best equipped to come up with that messaging right now? Certainly GOP members of Congress are very worried that the loss of healthcare and the tax cuts for the wealthy through the Big Beautiful Bill are not playing well across the country and will certainly hurt them. They’re not doing town halls. They’re trying to rebrand the bill. I’m just curious who you think right now is best equipped to put together that clear, cohesive plan, given the politics going into the midterms.

Charles Hua: Well, to be honest, I don’t think anybody actually right now has that plan. And if you look across blue states, red states, purple states, we get asked often, “Is there a model for a PUC or a state that’s doing all of this well,” and the answer is no. There is no single state that’s doing this well.

And I think what that means is that in this moment… First off, we would say that every state needs a utility affordability action plan that’s grounded in the policy substance, which we’ve gotten a little bit into and can certainly dig more into that topic. But on the political side, I think what we would like to see… Insofar as to Katherine’s point, this is becoming a political issue whether anybody wants that or not, and we can debate the merits of whether politicizing this issue is a net positive or negative, but the reality is that the voters view this as a truly non-partisan, or bipartisan issue, whatever you want to call it. There is fundamental agreement across all Americans that people don’t want higher utility bills. Perhaps that’s common sense, but what I think that means is that the opportunity is for Democrats, independents, and Republicans across the board to have more thoughtful approaches on this topic. And you can queue up the Spider-Man meme of everybody pointing their fingers at each other and blaming somebody else but themselves, but the reality is that we need to actually look inwards across the board and figure out what is actually driving up bills.

And to the earlier discussion that we had in this segment, it’s not really what is in the national media so much as the boring, less sexy pieces around our grid infrastructure, around extreme weather events, and if we can figure out a way to make sure that politicians of all political stripes actually have meaningful policy action that’s embedded in what should be pretty bipartisan solutions around getting more out of our existing grid, then that’s a path forward where this can actually create a winning political structure across blue, red, and purple states to tackle this issue around rising electric prices.

Katherine Hamilton: It would be awesome if this were bipartisan. I would just note that, first of all, you have this great database on PowerLine’s website of all of the rate increase requests or approvals, and I would just note that there are seven states, Arizona, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, that are also on the list of the top 15 states with the most clean energy jobs lost during the current administration, that all of any Republican state, any Republican member of Congress or the Senate voted for. So at some point, there will have to be a reckoning on where were the jobs lost, the jobs were supporting cheap, clean, quickly-to-develop energy resources, and also the rates are going up.

Stephen Lacey: Yeah. I totally agree with your premise, Charles, but we all know that that is not the state of politics today, and a lot of the messaging is going to come straight from the top. We have a president who is very eager and masterful at deflecting blame. We have a ton of groups on the left now squarely blaming the president for rising electricity prices. The nuance is going to be completely lost in this conversation. And so I think what happens with the president will trickle on downward to how parties position themselves around this. It’s just going to be extraordinarily partisan.

Charles Hua: Well, I think, just to add onto that, I don’t disagree with that, but I do think that the grid piece is fairly bipartisan in general as it relates to, in particular, say, the distribution system. Perhaps it’s bipartisan because nobody’s paying attention to it, which I think we need to preserve that sacred sort of space where that doesn’t become, from a partisan standpoint, politicized, the distribution grid at least. Fair enough, but that’s what I mean is that that piece of infrastructure, we do currently have a moment where we can achieve bipartisan consensus on that if we play our cards right. That’s how I see it.

Jigar Shah: I don’t know that I agree. I think the basic fact pattern around where we are today is not understood by anybody that I talk to. If you think about how much ink is spilled on renewable portfolio standards or solar and wind or natural gas when none of it matters, the bottom line, all of it is four cents a kilowatt-hour, all of it. You look at our generation costs, it’s the same as it was in 2010. We have had deflationary cost-drivers in generation. So all of it is not worth talking about. It’s all on transmission and distribution. And then when you talk about transmission and distribution, and you think about what those solutions look like, it’s all permission structures.

When you think about going to the VPP liftoff report or the grid-enhancing technologies liftoff report or all the things that we wrote down, 75 case studies, all those other things, and you go to any single state in the country… California is at the top of the list. They just eviscerated their budget for the DG program, and on top of that, it is not possible for behind-the-meter batteries to get compensated. The CPUC is going to war with people with batteries and saying, “We’re going to solve it with dynamic pricing.” Who the hell wants dynamic pricing when you just said that people don’t know what they’re paying for electricity day to day? Now we’re going to make it more dynamic? Yeah, that sounds like a great idea, Sherlock, over in California. But then you talk to people in Indiana where almost every single county is banning solar and wind, they’re trying to build a huge natural gas facility, and all of their rate increases are coming from distribution and transmission and not a single person in Indiana is actually even talking about it.

So what I worry about right now is that the culture wars are going to focus only on natural gas versus renewables. And when you say that, “I hope that distribution systems don’t get partisan,” it’s most certainly going to get partisan, because the way this is going to go is that people are going to say, “Do you want the big-bag utility that you hate controlling your thermostat, do you want them controlling your water heater?” That’s exactly where this is going to go. And so that makes the permission structure even worse. As soon as it becomes politicized, I don’t see how a public service commission actually deploys those technologies at scale.

So we’re in this weird spot right now where we all know exactly how to get more out of the transmission and distribution grid we already paid for. It’s called batteries and demand flexibility. We have been talking about it for 15 goddamn years on the Energy Gang podcast, and now on Open Circuit, and it’s still not clear to me that that is an acceptable answer to all the parties around the table.

Charles Hua: Well, and I think just to respond to that real quick, the reason why we haven’t done any of the things that we’ve been talking about for decades is because our incentive structure in our regulatory system hasn’t created the incentives for that. And I think in order for us to have a significant 180 from that reality, we do need people to take a step back, take stock of the regulatory system, figure out what’s working about it, what’s not working, and figure out what needs to be reformed. And I do think that the affordability conditions that we’re in create the political permission structure for some of those reforms in the absence of utilities in the current regulatory system feeling like they have the capital I incentives to adopt grid-enhancing technologies and other solutions that we’ve talked about.

How could we cut electricity prices 20% by 2030?

Stephen Lacey: Well, that brings us nicely into the last part of the conversation, which is, what’s in our plans here? So we’ve touched on a few of the solutions around regulatory reform, but Jigar, you posed a question to us when we were talking about the format for this show and you said, “Let’s imagine you’re a governor and you promised to voters, ‘I’m going to cut your bill by 20% by 2030. What should be in our plan?’” Maybe since you posed that question, Jigar, you can start. What’s in your plan?

Jigar Shah: I think that it all comes down to minimizing the investment of physical upgrades to transmission distribution. Some of it has to be done because it’s just maintenance CapEx, right? Some stuff is just old and it has to be replaced. Got it. But we have so many studies that show that we can absorb 3.5% load growth every single year for a long time without upgrading significantly our transmission distribution.

But the only way that that works is you have to upgrade the service level agreement between the utilities and the customer, so you say to the data center, “You want to connect? Great. But that means you have to be flexible for 150 hours a year. And whether you make that flexibility because you add batteries to your site, or you just agreed not to run for 150 hours a year, that’s on you.” The same thing’s true with people who put in electric vehicles. “You want to put an electric vehicle in? Great. We actually are going to give you a much cheaper rate, or we’re going to basically only let you charge for these 20 hours a day, and these other four hours, we get to curtail you.” And I just think that we are in this moment right now where you have unprecedented load growth.

So for the first time in a long time, the denominator of the number of kilowatt-hours that we’re selling is going up, which is what we’ve been praying for for 20 years. And now, as the cost structure becomes normalized because we start deploying all these technologies that, God forbid, we’ve been working on for 20 years, then we actually have the ability to get more out of the system that we’ve already paid for. So that’s pull transformers. We can’t keep upgrading those. We got to use flexibility at the subpanel. We got to make sure that all of these connected devices that everyone’s buying right now has an ability to be useful in this moment in the system. We have to have transparent ways for people who have behind-the-meter batteries to get paid. It’s shocking to me that the people at the front of the pack right now are Holy Cross rural co-op and Rocky Mountain Power, that no one else seems to have a transparent way. I’ve had a battery here in Maryland for eight years. I still can’t figure out how to get paid for this battery to help PEPCO.

And so when you think about just how far behind we are at just letting people who have already independently decided that battery is their technology of choice for their backup generation to get paid to help their neighbors, that is a confounding conversation across the country. It is not transparent at all. And we recently raised over a billion dollars in venture capital led by Andreessen Horowitz into our sector, into a new crop of companies who are doing nothing but selling this solution nationwide. And they don’t have permission in most places to sell their solution. That, to me, has to be the center and the locus of our efforts.

Stephen Lacey: What’s Katherine Hamilton’s action plan?

Katherine Hamilton: Well, Common Charge is a group that we just launched, has sort of five core principles that we think get to this affordability, also reliability [inaudible 00:57:19]-

Stephen Lacey: Oh, you have the official list. You’ve got a real-

Katherine Hamilton: Official list.

Stephen Lacey:… well-thought-out official list.

Katherine Hamilton: Number one, open and fair markets, everybody participates; number two, equitable access, public benefit, hello, and participation; number three, proper valuation, compensation, Jigar, and cost transparency; number four, rate payer autonomy and choice; and number five, innovation, system transformation, and collaboration. So we already have these five principles laid out, and then you can look at any policies and figure out, do they stack up? Are they things that we need to bring in? And historically, energy efficiency, what the heck, y’all? We should be doing this everywhere. They’re consistently the cheapest alternatives as getting energy efficiency out, 2 to $4 in benefits for every dollar spent, 790 billion saved since 1990. So I feel like energy efficiency is going to be huge.

The other piece, I know, Jigar, you were talking about New York state, well, there is something that’s very interesting that’s happened. And I would love to hear Charles’s views on performance-based rate-making, because certainly in Hawaii and Connecticut, they’ve been sort of leading the charge on this and coming up with kind of carrots to utilities to be compensated based on performance. But New York State did something different. They have something called a negative revenue adjustment that they just approved that basically fines the utilities if they don’t perform and don’t compensate customers fairly. And that’s pretty interesting. And what that means is that they’re not only measured on what they’ve traditionally been measured on, but also on the ability to get customers the public benefits that essentially they’re tasked to do; they just are not always compensated for, or incentivized for. So I think that one’s a really interesting case too. There are lots of other different types of policies that we could talk about, but I’m very interested in, Charles, in your views on performance-based rate-making.

Charles Hua: I think the thing about performance-based regulation is that it is highly complicated, technical, complex, and frankly, labor-intensive. And that’s why we haven’t seen more PUCs really take that up over a sustained period of time. The average public utility commissioner only serves in their role for about four years, and with the examples that you mentioned, some of those have been fairly intensive efforts from individual commissioners who have had the motivation to lead those efforts. And it’s not clear that on a sustained basis, just the level of PUC staff capacity is sufficient to make sure that you’re setting the right metrics that are not easily gameable, that actually are reasonably ambitious and move the needle in terms of performance.

And that’s what I mean by lowercase I incentives in this moment where all regulation is incentive regulation. And to the extent that a given regulatory body is not fully squeezing its juice in terms of the authority that it has legally to push different stakeholders to their fullest ends in terms of an affordability mandate or charge, then I think what I would say is that, at minimum, every regulatory body needs to be a lot more hyper-focused on affordability-centered solutions as the core outcome, and not economic development first and affordability second.

Stephen Lacey: And so are there any other pieces of your action plan that you think would actually materially cut rates, like 20% by 2030 that Jigar mentioned?

Charles Hua: Yeah, and just to put some other numbers on the table, Tyler Norris in the Duke paper showed that our grid utilization rate is fairly low. It’s around 50 to 55% depending on the market. And what that means is that if we can get that number up to 60, 65, 70 by getting more out of our current grid, we can put significant downward pressure on electricity rates, and therefore utility bills. I would also put out there that there’s that statistic roughly 10% of our system costs are to service only 1% of the hours; the notion that we need to take a serious look at peak demand, and we’re freaking out about load growth and rising electricity demand, but we need to be very, very serious about what we’re doing to put downward pressure on growth to that peak demand metric. And any number of the solutions that we talked about today can help with that.

But we talked about some other things within integrated resource planning. Most states have an IRP process, but they’re not doing best-practice IRP planning, including things like better load forecast parameters, better cost assumption frameworks, and actually illuminating a probabilistic scenario. So if you’re a regulator and you look at a line, a singular line for load forecasts going into the 2030s, you take that as gospel, when in reality you ought to be asking, “What is the 5%, 95%… What is that confidence interval that actually shows the range of options and how it impacts bills?” That’s not a question, for instance, that I’m seeing enough regulators ask, when they ought to be figuring out how the different scenarios will lead to different outcomes, particularly in a highly volatile, global, macroeconomic environment.

But to get at your question on an affordability action plan, I would reiterate that every state needs an affordability action plan, and ideally the governor is working in tandem with the state legislature and the PUC to make sure that there’s actual coordination across traditionally siloed buckets in terms of who has stakes in the regulatory system. So for some of the incentive restructuring questions that we’ve been talking about, Katherine and Jigar, that needs to be, in some instances, something that the PUC leads, in other instances, something that the state legislature needs to create a new framework around. But it has to be all coordinated. And we need to make sure that we’re also holding the political officials accountable, too, because there’s maybe two circles, a Venn diagram, of what’s good from a political standpoint and what’s good from an actual policy standpoint around tackling this issue, and the intersection is very, very robust. It’s all of the things that we talked about. But we are largely seeing things that are more on the band-aid side of the equation in terms of what’s low-hanging fruit, political brownie points, and we can’t get away with that if we’re actually to address this issue in a meaningful way.

In order for us to get there, though, I do think that as everyday consumers, people need to make their voices heard to those different stakeholders, in addition to the large commercial and industrial customers and even the data centers to be able to say, “Look, as a collective consumer class, we want downward pressure on electricity prices.” And rather than spend all this time fighting between customer classes, I think and we think that making sure that the size of the overall pie doesn’t just balloon beyond reproach is a better use of our collective energy and time than trying to fight shares within that pie, because the potential risk for massive increases in rates is just so profound in this moment that we can’t afford to do anything but work together across these different stakeholders and make sure that the system is working as a whole for consumers of all stripes.

Stephen Lacey: Well, it has been incredibly frustrating to see how the regulatory apparatus has been unable to catch up to some of these solutions, but you’re doing really amazing work to try to change that, Charles. And I do remain pretty optimistic that this is a crucial moment for making DERs and grid-enhancing technologies a real painkiller, Jigar used that phrase, turning them from vitamin pills to painkillers, which is a common phrase in the tech industry. And I definitely agree that as we make that transition, that we are going to see significant change, at least I remain optimistic that that will happen. And I know you’re really on the front lines working on this stuff, and I really hope it continues to bring impact that we can measure.

Charles Hua: Well, and I want to close with an anecdote, which is our team had a retreat in New Orleans, and we had an Uber driver who, he was a restaurant manager, his wife was a school teacher, and he grew up in New Orleans. And he shared with us that he had to move out of New Orleans, and the number one reason was because of utility bills, because they changed too much month to month and because they were too high, which is a pretty remarkable and damning statement of our current condition. But it’s actually, from my point of view, a pretty optimistic story in that he had asked us, “Can you explain what a fuel adjustment charge is?” And I think it’s actually pretty revealing that right now consumers are very much earnestly trying to figure out what’s going on and asking questions and trying to engage. They may not have all the answers. And we had asked him, “Do you know what the Louisiana Public Service Commission is,” and he said no, but with that shining a light on these bodies that have so much influence and power, that’s what we need in this moment is to truly empower the consumer voice so that folks can feel like they are represented in and can influence the outcomes that ultimately impact them as consumers.

And so I think we need to take a close look at why we set up the utility regulatory system in the first place, which is to take advantage of this incredible invention and commercialization of electricity as a fundamental good that powers our modern economy and day-to-day lives, and put back in the center of our system the consumers. And I think what gives me hope and optimism in this moment is that there has not been a better time in decades for that consumer voice to shine than in the current moment. We just need to make sure that it results in productive outcomes to put downward pressure on rates and utility bills going forward.

Stephen Lacey: And every good story starts with an observation from an Uber driver. Charles Hua is the founder and executive director of PowerLines. Thanks again.

Charles Hua: Thanks for having me.

Stephen Lacey: You can read the Utility Bills Are Rising report from PowerLines. We’ll link it in the show notes, and we’ll also have some of our other stories at Latitude Media linked there. As always, you can find lots of our coverage related to the conversations here at latitudemedia.com, along with our newsletters. Katherine Hamilton and Jigar Shah are my co-hosts. Katherine, thank you.

Katherine Hamilton: Thanks. Have a great rest of the week.

Stephen Lacey: Jigar, good to see you.

Jigar Shah: Always.

Stephen Lacey: And do us all a favor. You’re doing a real personal favor to all of us to go to the app where you listen to this show and give us a review and rating. And if something grabs your attention, give us a shout-out on LinkedIn or wherever you express your opinions.

Open Circuit is produced by Latitude Media. The show is edited and produced by me. Sean Marquand is our technical director, and Bailey is our senior podcast editor. And we will catch you next time. Thanks for being here.