Some of art history’s boldest pieces favor those with a unique perspective.

An art show featuring six neurodivergent artists is coming to the Philly area this Friday. The show, LOOK HERE, takes place at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery and highlights the work of artists from Greater Philadelphia with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Each artist is connected with the Center for Creative Works (CCW), a progressive studio that works with neurodivergent artists.

Brandon Spicer-Crawley, “Me, You”, 2019

Brandon Spicer-Crawley, “Me, You”, 2019

“Although it’s an exhibition of six artists working out of the Center for Creative Works, we were not trying to label it as a disability art show,” said Jennifer Gilbert, one of the show’s curators. “This is six contemporary artists working today out of a studio. They just happen to get a bit more support than everybody else.”

Gilbert is a U.K.-based curator, whose work supports artists with disabilities. She curated the show with two CCW artists, Paige Donavan and Mary T. Bevlock.

Instead of having photographs of each artist, Bevlock — who is known for her portraiture work — created images of each artist, which appear alongside the work.

LOOK HERE’s inclusive gallery space. (Courtesy of Sara Griffin)

LOOK HERE’s inclusive gallery space. (Courtesy of Sara Griffin)

“The show is going to be amazing,” said Donavan, whose work spans paintings, drawings and needlepoint. She has showcased at the Outsider Art Fair in New York City and the Crawford Gallery in Ireland. “We chose [these artists] … We put everything together,” she said of her first-ever co-curated show.

The six artists featured in LOOK HERE are Kelly Brown, Cindy Gosselin, Clyde Henry, Tim Quinn, Brandon Spicer-Crawley and Allen Yu. While the artists all work with CCW, the pieces featured are quite varied.

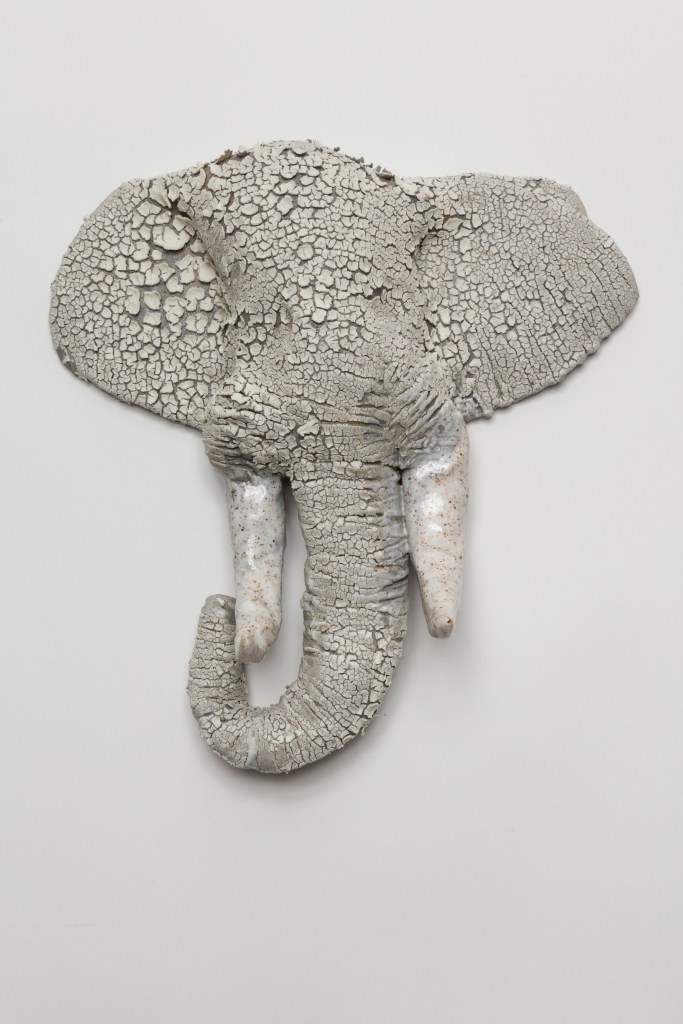

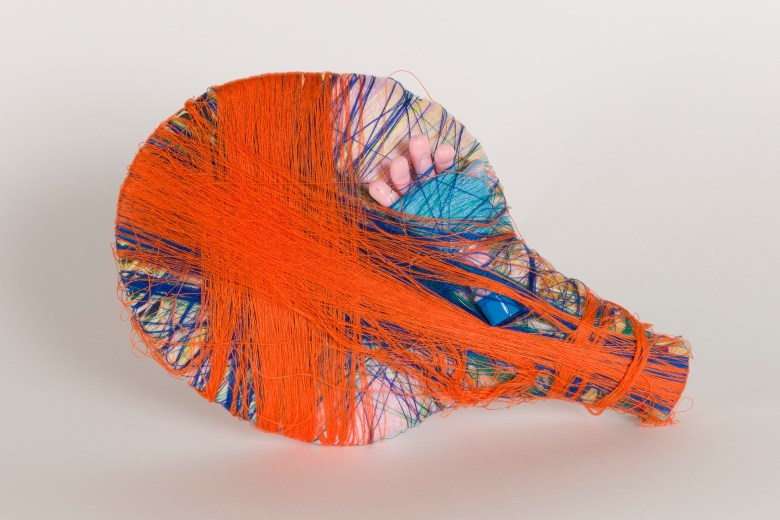

Gosselin makes mixed-media sculptures. She is a blind artist and wraps found objects like Barbie dolls and markers in yarn — creating purely through her sense of touch. Some of her sculptures are quite small, while one is taller than she is. Henry creates textured ceramics, which feature charming and detailed animal heads. His elephants, hung on the wall, are particularly striking. Yu, on the other hand, draws with markers, repeating images he’s attracted to — trains, fast food, animals and candies.

Drawings from artist Allen Yu. (Julia Binswanger/ Billy Penn)

Drawings from artist Allen Yu. (Julia Binswanger/ Billy Penn)

A couple of his pictures feature fast-food burgers and chicken sandwiches from different parts of the world, drawn with care and specificity. Yu is a well-traveled artist. Some of them he’s actually tried. Others he’s done research on. A couple fun ones feature Burger King’s black buns, made from squid ink in South Korea.

“I like to try something different,” Yu said of his approach, emphasizing how much he enjoys the detail-oriented nature of the process. “I like to make art because it’s fun.”

Making galleries more inclusive

The space is designed to be as inclusive as possible to all types of people. Paintings are hung about six inches lower than the average gallery height, so that visitors in wheelchairs don’t have to strain their necks to look up. Sensory backpacks with headphones and fidget objects are available at the gallery entrance.

The beginning of the show also includes braille, easy-read and large-print booklets for anyone who wants them. There are videos about the artists — from which visitors can learn more about their background — with ASL embedded for those with hearing impairments.

Paige Donavan at the Center for Creative Works in Kensington. (Julia Binswanger/Billy Penn)

Paige Donavan at the Center for Creative Works in Kensington. (Julia Binswanger/Billy Penn)

“You’ll notice there’s a couple of benches in the space,” Gilbert said. “Rather than just have a plain, comfortable thing to sit on, we’ve commissioned two of the artists in the show, Brandon and Tim, to do a design which we’ve made into the seating.”

Bevlock and Donavan helped write the labels next to each artwork, so that the language at LOOK HERE is playful and accessible. After all, sometimes gallery labels can feel dense — describing art with words that can only be found in the latter half of the SAT’s vocab section.

Donvan and Bevlock describe Quin’s artwork — which is abstract, colorful and geometrical — as having qualities that remind them of “waterslides” and “candyland.” “We feel his works on the black backgrounds are really ‘punchy,’ ” the label reads, “with a striking appearance, next to the bright rainbow colors he often chooses to use.”

Tim Quinn, “Untitled”, Brooke’s Room, 2016

Tim Quinn, “Untitled”, Brooke’s Room, 2016

In addition, LOOK HERE is inclusive for those who are visually impaired. There are QR codes with audio descriptions, as well as “please touch” installations, where visitors can feel the textures of the artist’s materials.

Brown’s artwork includes layered fabrics that hang in colorful, woven layers. “Don’t you just want to touch these? They’re so tactile and squishy,” the artist label reads.

Well, we do. And, you can. You don’t have to have a disability to want to partake in this aspect of the exhibition.

And the sense of touch isn’t the only one to be included.

“We made a sign with Jennifer and Mary that some people can scratch and sniff,” Donavan said. “When you go to Allen’s work, you sniff some of his burgers.” (Note that the burger smell ended up being “a bit sickly,” according to Gilbert, so they used a chocolate scent to evoke Yu’s ice creams instead.)

Neurodivergent artists with a platform

Gilbert noted that when it comes to artists with intellectual disabilities, sometimes language is not necessarily the strongest way to get across a point or idea.

“For some of these artists, [art] is like a communication tool for them,” Gilbert said. “Their artwork is communicating something that the artist wants to communicate in a way suited to them. And it’s respecting that and respecting that artist, and knowing they are doing the best of their ability. This is their own unique, individualized practice.”

The LOOK HERE show would not be possible without an inclusive art space where the artists can create and collaborate.

For these six artists, that space is CCW, which has studios in Philadelphia and Wynnewood. The studio is dedicated to not only fostering the talents of artists with disabilities, but also helping them gain visibility and credibility.

“We work with artists who receive a particular kind of funding through Medicaid called the consolidated waiver, which supports day programming for those adults,” said Samantha Mitchell, CCW’s exhibitions manager. “We have a really wide range of people who work with us. I think currently, our youngest artists are 21 and our oldest is 85.”

CCW’s working artists come to the studio five days a week, from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. The artists choose the medium and subject that they want to explore artistically.

“We have some people who are weaving, working on textile art,” Mitchell said, describing the scene at CCW. “We have some people who are painting, doing kind of photorealistic paintings. We have some people who are working with ink … So, a lot of different media.”

Gilbert hopes that LOOK HERE will challenge preconceptions of artists with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

“There’s so many misconceptions,” she said. “Some of the main ones that I often hear over in the U.K., and I know I’ve heard it when I’ve been in America as well, is that it just looks like a child has created the artwork. Or, you know, ‘Oh, I could do that myself.’ And it’s like, well, pick up a pen and paper and demonstrate that to me, because I don’t think you could.”

Certainly, CCW’s artists wouldn’t be the first creatives to have the critique leveled at them. Even the greats — Pollock, Basquiat, Duchamp — may seem elementary to the uninformed. In fact, one of Spicer-Crawley’s works — which feature expressive, abstract figures — is painted over a print of Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase.”

Cindy Gosselin, “Untitled”, 2022

Cindy Gosselin, “Untitled”, 2022

Expanding opportunities for artists with disabilities

LOOK HERE opens Sept. 19 and runs through Dec. 13.

In addition, CCW is also putting on another sister show in conjunction called LOOK THERE, which is also curated by Bevlock and Donovan and exhibits one work from all of CCW’s 99 Wynnewood and Philadelphia artists. There’s also a third monthlong exhibition at Atelier Gallery, LOOK EVERYWHERE, curated by Gilbert and opening Oct. 1, that showcases artists from progressive studios across the country.

Gilbert is hoping that the lineup will inspire other galleries in the city to keep artists with intellectual disabilities in mind when they are putting together exhibitions. What’s more, she noted that it isn’t so hard or expensive to add accessible elements to exhibitions, like the sensory backpacks, “please touch” elements and beyond.

“It’s about including them in shows like you would include anybody else,” she said. “So not necessarily having to do a disability art show in your institution, but having a group show and having these people seen on an equal footing alongside some of the greats that are seen in the contemporary art world today.”

Yu is quite ambitious. He said that he hopes people take in his work as both “authentic and iconic,” and would love to see his pieces displayed in galleries around the globe.

“I want my artwork to be sold in Japan or South Korea or London,” he said.

Allen Yu creates a drawing of one of his favorite candies, M&M’s, at CCW. (Julia Binswanger/Billy Penn)

Allen Yu creates a drawing of one of his favorite candies, M&M’s, at CCW. (Julia Binswanger/Billy Penn)

Expanding possibilities for artists with disabilities is certainly achievable. Judith Scott, whose work will be included in LOOK EVERYWHERE, has also had a retrospective in the Brooklyn Museum. Just last December, MoMA featured its first-ever exhibition around a developmentally disabled artist, Marlon Mullen.

Still, cuts to Medicaid could hamper studios with missions like CCW’s.

“There’s a chance that lots of these studios will actually disappear and these people will just go back into their lives, and some of them might not be able to access some of the materials at home, or get some of the support they need to make art,” Gilbert said. “So, it’s a really pivotal moment right now.”

Gilbert’s hoping the shows will help people see the importance of lifting up neurodivergent voices.

“That’s what I really advocate for and push for,” she said. “So that everyone is seen just as an artist in the same way that they should always be seen, and everyone should be hung, displayed, written about, in the same way that any artist should be.”