Kyle Harrison was the headliner in the Rafael Devers trade. While Craig Breslow said the Red Sox might win more games without Devers, to me, the deal was always a move for the future. Jordan Hicks is a pitcher who needs an offseason of work under his belt to be unlocked. James Tibbs got shipped off for Dustin May, which never really made sense to me because Dustin May also felt like a pitcher who needs an offseason of work to be unlocked, but he was on an expiring deal so I guess the Red Sox thought otherwise. Harrison was a highly touted prospect who had already debuted in the majors but never really reached the heights many thought he could. He’s still young and a work in progress, but he also feels like a pitcher who needs an offseason to reach his potential. With an injured list of pitchers as long as a CVS receipt, he didn’t have that luxury before he was called on, and now he’s a key part of a pitching staff in the middle of a playoff hunt. So what do we have in the lefty?

Harrison is difficult to evaluate because he’s bounced around from level to level so often. But he made 24 big league starts in 2024 and threw 124 innings. If a numerologist could explain the significance of the number 24, I would appreciate it. Until then, I’ll use 2024 as a jumping-off point.

Every pitcher should really be considered two pitchers: one against lefties, and one against righties. Of course, the sum of the two parts determines one’s overall ability, but breaking it down by side gives us a better picture.

Advertisement

Against lefties, Harrison has a two-pitch mix that works for him. He pitches backwards, using his curveball early in counts and his four-seam fastball to put hitters away. They hit .260 against him, but that’s in part due to poor batted-ball luck and a small sample size, as opponents loaded lineups with right-handed hitters. His 21.3% K-BB% was a stellar mark, and usually a predictor of future success.

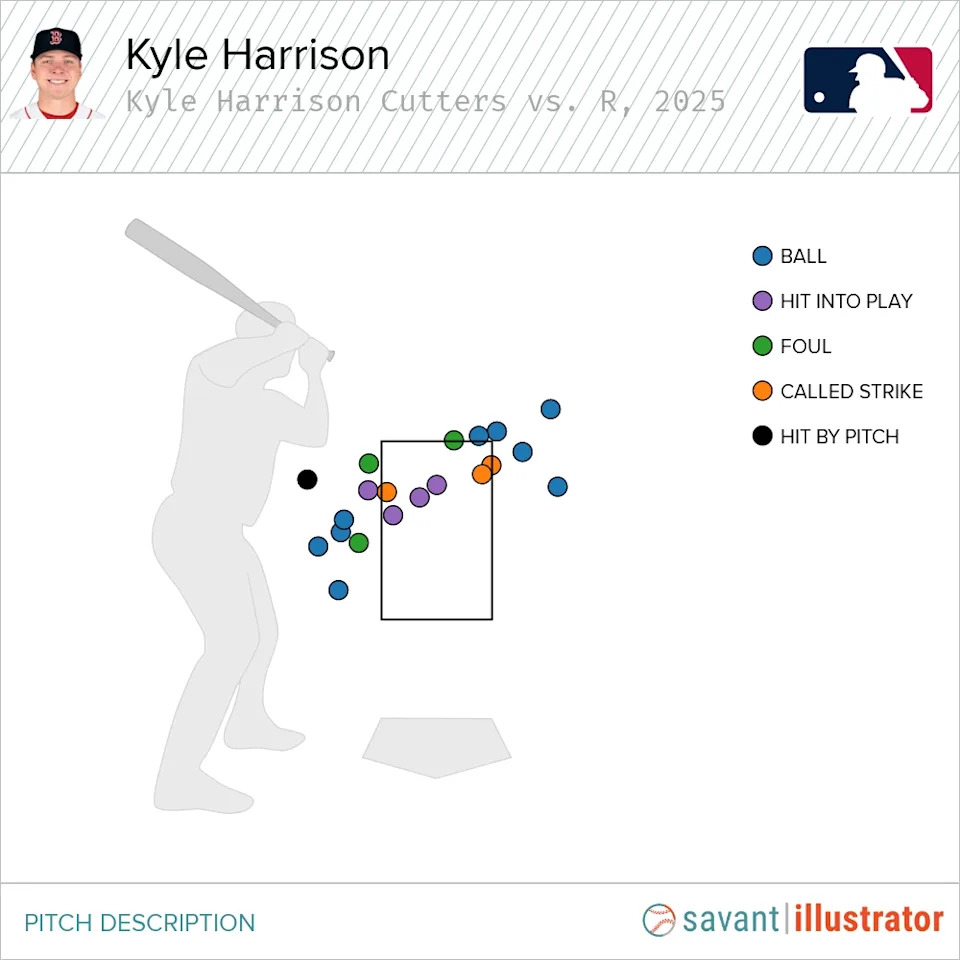

Against righties, his arsenal doesn’t play as well. He tries a similar approach, using a curveball and changeup early and turning to his four-seam with two strikes. That approach required the big, slow curveball that breaks toward right-handed hitters to be in the zone, where it was hit hard. His changeup wasn’t in the zone enough to consistently earn strikes either. To fully unlock Harrison, he needs a pitch to throw to right-handed hitters for strikes.

When the Red Sox acquired Harrison, they sent him to Triple-A to find that pitch. They followed the advice of every internet pitching guru* ever: “just** add a cutter”. It’s never as easy as “just add a cutter***”, though. In his first start against Tampa, Harrison used his cutter, but didn’t command it effectively enough for it to be the strike-getter he wants it to be.

They also altered his changeup grip, opting for the flavor-of-the-month “kick change”, which provides an additional drop at the expense of horizontal movement. They also flipped his game plan, opting for more early fastballs and cutters, using the secondary pitches later in counts. Overall, the plan worked for six innings of one-run baseball in his first start for the Red Sox against the Rays. Still, I can’t help but wonder how repeatable it is. Let’s take a look at how it looked in practice.

Advertisement

*I don’t claim to be a guru, but I did suggest this exact thing for another publication on the night Harrison was acquired.

**It’s never this simple. They let anyone write things on the internet, even me. Who decided I was qualified?

***But… they did almost immediately give him a cutter, so maybe I was on to something and am qualified?

We’ll start with Junior Caminero in the fourth inning.

Here’s a perfect cutter to start the at-bat. It lands perfectly on the high, inside corner of the strike zone. The shape isn’t anything insane, but it has enough horizontal movement towards the batter that it will create called strikes and foul balls. Early in counts, he can throw this up and in, or backdoor for a called strike. Great start.

Advertisement

Here’s a cool idea, but it isn’t executed. He tries to throw a four-seam fastball to the same spot, but misses inside. By throwing another fastball in the same location, he’s betting that Caminero will think it’s another cutter and leave it, thinking it will cut off the plate, taking a called strike when it doesn’t break. As far as misses go, this is a good one because it’s inside rather than over the plate.

He goes back to the cutter, hits his spot again, and Caminero can’t get the barrel to the ball. This is exactly how the cutter should be used. It doesn’t need to generate swings and misses, just early strikes, and weak contact. The issue is he hasn’t found the feel for the pitch just yet. It’s early, but so far, he hasn’t hit the quadrant of the zone he’s aiming for frequently enough.

Harrison only recently turned 24 years old, and he started throwing the pitch in June. It’s hard to learn a pitch on the fly, and he’s incorporating it against major league hitting. The command needs to be better, but with an offseason of work, that could become a reality. If the cutter can become a reliable pitch and allow him to drop his four-seam usage against righties from 60% to about 45%, he should see his walks drop and his strikeouts rise.

Advertisement

Without the cutter, he has a four-seam fastball, slurve, and changeup that he can throw to righties. The four-seam is excellent. Its velocity has been down recently, but I’d expect the Red Sox’s offseason improvement plan for Harrison to include adding velo. Even at 92 mph, its 1.7 height-adjusted vertical approach angle is an outlier, helping the pitch playup. The slurve has never missed bats at a high rate, in part because the shape isn’t one that typically plays to the opposite hand. It’s slow at about 81 mph, and really needs to be located at the back foot to generate whiffs.

Here’s an example of the issue with his slurve. On the previous pitch, Mangum fouled off a slurve that was slightly higher than this one. The second time around, he was able to get around it and double down the line. He’s always used the slurve, but I wonder if a harder breaking ball is the answer.

The changeup has shown flashes, but as I mentioned, it’s new and isn’t a dominant left-handed changeup like you see from Christopher Sanchez or Tarik Skubal. Here’s a good one.

With Harrison’s fastball, a well-spotted changeup should be a solid weapon. Since joining the Red Sox, he’s only thrown it seven times, which makes me think he’s not overly confident in the feel just yet. FanGraphs’ Stuff+ model likes the new shape, but the command isn’t on par with the stuff just yet.

Advertisement

Harrison is a project, but the bones are there. He was the biggest piece of a trade involving a nine-figure player, so it’s easy to expect a lot out of him. With an off-season of work under his belt, I think he can become a reliable part of the rotation for years to come. For the rest of this season, he’s probably best used in small samples.