Microsoft wants to cool processors with microchannels in the silicon chips much more efficiently than before. The company has trialed microfluidics for its own servers in several test runs: Together with an unnamed manufacturing partner, Microsoft is etching channels into the top of the chips. Coolant flows through these channels, which would otherwise run through copper plates (cold plates) above a processor or accelerator.

Coolant directly in the chip bypasses various heat transfers: between the chip and coldplate and between the coldplate and water. Unfortunately, Microsoft only mentions relative improvements in one article: Heat dissipation is said to be three times better compared to previous water cooling. “The maximum temperature rise of the silicon inside a GPU” is said to be reduced by 65 per cent.

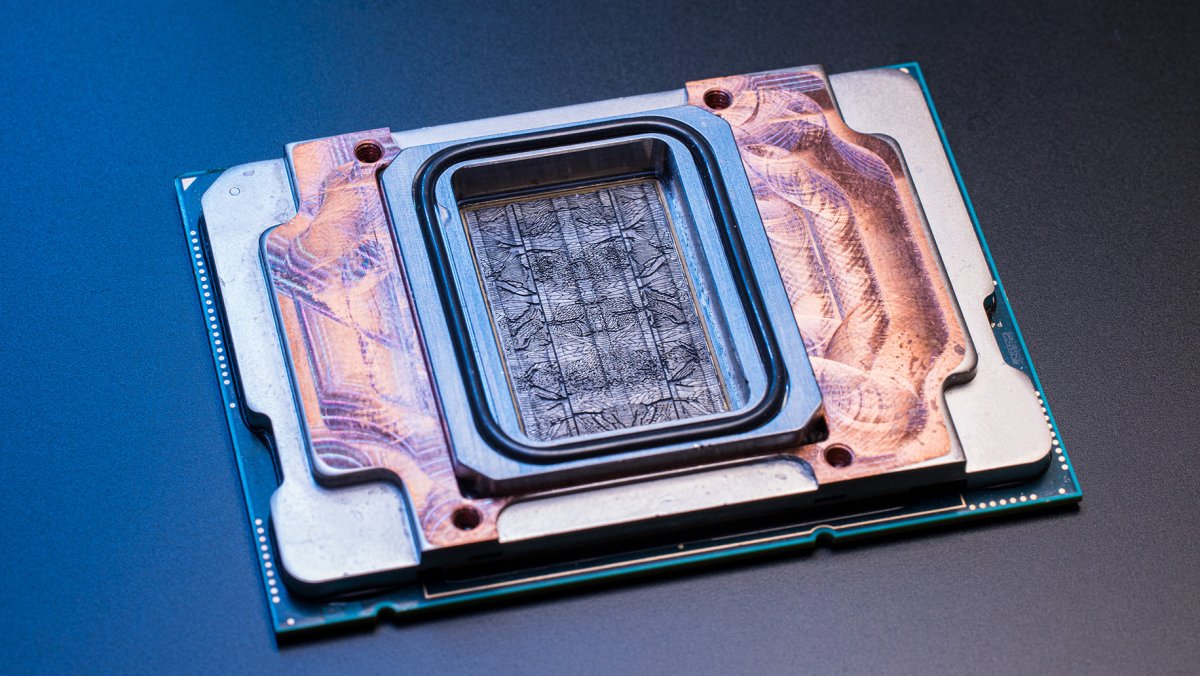

The current microfluidic iteration is said to be inspired by plant leaves: instead of etching a uniform gate into chips, Microsoft is focusing on asymmetrical channels. The arrangement is intended to cool hotspots such as computing cores even better. The finest channels are about as wide as a hair.

Microcranal structures in the test chip.

(Image: Microsoft / Dan DeLong)

Old concept

Meanwhile, manufacturers have been researching cooling channels in chips for decades. IBM, for example, published its first research work in 2006. Until now, however, it has struggled with implementation: cooling systems must be fundamentally redesigned; above all, they must have direct contact with the chip, but be thoroughly sealed around it. Microchannels must not be blocked by impurities. Chip contract manufacturers such as TSMC must also adapt their production.

The topic is now coming up again because the energy density of AI accelerators in particular is increasing rapidly. Nvidia’s Blackwell GPUs, for example, already exceed 1000 watts; the 2000 and 3000 watt marks are likely to fall in the upcoming years.

A test board with a customised cooler for the microchannels.

(Image: Microsoft / Dan DeLong)

Microsoft is aiming for series production

So far, these are only prototypes. Next, Microsoft wants to investigate whether and how microfluidics can be integrated into its own chips on a large scale. The focus is on ARM processors from the Cobalt family and AI accelerators from the Maia family, which TSMC manufactures for Microsoft. Ideally, partners could also convert their own chips, such as Nvidia. However, it is likely to be at least a few years before this happens.

In the long term, microchannels could facilitate cooling in stacked processors, Microsoft also writes. Heat generation is one of the biggest problems with stacked chips. With previous cooling systems, the waste heat from the lowest chips must first pass through the upper layers before it can be dissipated. Microchannels in the chip could make it possible to cool several chip layers in parallel, IBM mused back in 2008, although the implementation would be even more complicated than with normal processors.

(mma)

Don’t miss any news – follow us on

Facebook,

LinkedIn or

Mastodon.

This article was originally published in

It was translated with technical assistance and editorially reviewed before publication.

Dieser Link ist leider nicht mehr gültig.

Links zu verschenkten Artikeln werden ungültig,

wenn diese älter als 7 Tage sind oder zu oft aufgerufen wurden.

Sie benötigen ein heise+ Paket, um diesen Artikel zu lesen. Jetzt eine Woche unverbindlich testen – ohne Verpflichtung!