New fossil and genetic evidence shows that woolly and Columbian mammoths were not just distant cousins roaming separate parts of Ice Age North America — they were interbreeding for tens of thousands of years, creating hybrid lineages that adapted to shifting climates across the continent. The findings, published in the journal Biology Letters, suggest that hybridization played a far greater role in mammoth evolution — and possibly their survival — than previously thought.

Unexpected Encounters Across Ice Age Landscapes

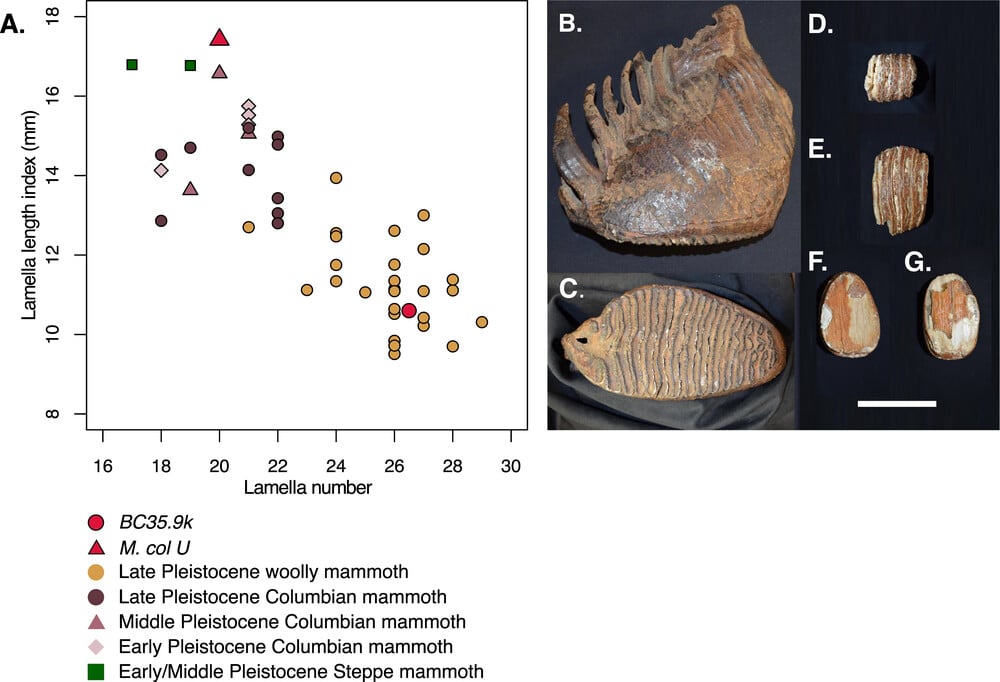

Two mammoth molars unearthed in British Columbia, Canada, are rewriting what we thought we knew about mammoth evolution. Once believed to have lived largely separate lives—woolly mammoths in the colder north and Columbian mammoths in the temperate south—the species appear to have overlapped and interbred repeatedly over a span of at least 40,000 years.

DNA analysis revealed that one mammoth tooth dating back 36,000 years contained 21% Columbian mammoth DNA, while a younger tooth from 25,000 years ago showed an even stronger 35% Columbian heritage. These findings suggest long-standing gene flow between the species, reshaping the evolutionary map of North American megafauna.

Hybrids That Broke The Evolutionary Rules

The traditional view of evolution—of distinct species slowly diverging along neatly branching family trees—is being challenged by these hybrids. According to Professor Adrian Lister of the Natural History Museum, the study supports a growing body of evidence that hybridization can drive evolutionary innovation rather than disrupt it.

The hybrids didn’t just survive—they thrived. Despite carrying mixed genetic heritage, their teeth remained morphologically similar to the high-crowned, ridged molars of woolly mammoths, adapted for grazing on cold, grassy tundras. This suggests that natural selection preserved the physical traits best suited for survival in harsh Ice Age environments, regardless of genetic blending.

Tracing Hybrid Origins Through Deep Time

This research builds on a breakthrough from 2021, when scientists pulled 1.2-million-year-old DNA from a steppe mammoth tooth found in Siberia. That ancient lineage seems to have mixed with early woolly mammoths, eventually giving rise to the Columbian mammoth in North America — a species that may have inherited up to half of its DNA from woollies.

Now, things are coming full circle. New data shows the gene flow didn’t just go one way — Columbian mammoths were also passing DNA back to woolly mammoths. In fact, sex chromosome analysis hints that most of those pairings were between male Columbian mammoths and female woollie.

They Survived When Others Didn’t

This long-running hybridization may have helped mammoths weather the volatile climate swings of the Pleistocene. Hybrids showed higher genetic diversity, often a marker of adaptive potential. It may not have saved them from ultimate extinction, but it likely prolonged their survival during a period of dramatic glacial advances and retreats.

As Lister points out, “Understanding how species can mitigate environmental change is very important at the moment. By looking back at how mammoths coped, we might better predict how modern animals—like elephants—will adapt to today’s accelerating climate change.”

A Tooth Just Flipped Modern Conservation on Its Head

This discovery isn’t just about mammoths — it could help save animals alive today. Take the case of the Scottish wildcat, a species now critically endangered due to interbreeding with domestic cats. Studying how extinct hybrids like these mammoths responded to genetic mixing could offer valuable insights into how we manage vulnerable species facing similar challenges.

What’s remarkable is that this entire evolutionary story was reconstructed from just two fossilized teeth. Not a full skeleton, not a well-preserved carcass — simply two molars. Yet from those fragments, scientists were able to piece together tens of thousands of years of interspecies interaction and adaptation. That’s the power of ancient DNA: a single sample can open up entirely new perspectives on how life evolved — and how it might continue to survive.