“Lost Last Poems”

By Shannon Gramse; Cirque Press, 2025; 123 pages; $15.

Shannon Gramse’s “Lost Last Poems” is no ordinary poetry book, and there is neither anything “lost” nor “last” about the poems. Instead, the book is based upon a clever and entertaining conceit.

In “An Annotator’s Forward,” the “annotator” — S.G. — explains that the mysterious manuscript was found on a USB drive by a snowboarding student and that he examined it reluctantly one evening. “Despite the collection’s creaks, I was charmed and wondered about the author.” He finds from “textual evidence” that the poems might be “the work of an Alaskan dad with common Late-Empire concerns.” He wonders if publication might solve the mystery of the poems’ authorship but hopes not. The poems without a poet can simply be a gift.

And then, we’re off and running. The faux annotator presents the alphabetized poems as a Wunderkammer, a catalogue of curiosities. “Diverse personae confound orthodox identity poetics, and an oddly Orientalist counterpoint runs throughout to dispel provincialism. I humbly append annotations on the poems and their sources …”

The 59 alphabetized poems begin with “Approaching King Island” and end with “Zen Erratic” and are followed by 20 pages of scholarly annotations that attempt to explain references in the poems and the historical or cultural material that the unknown author might have drawn from.

Gramse, who teaches writing at the University of Alaska Anchorage and co-founded and co-edited, with Sarah Kirk, the discontinued literary journal “Ice-Floe: International Poetry of the Far North,” has not only had fun with his fictional project but proved himself, with this first book-length poetry collection, a poet of the first rank. Before its publication, “Lost Last Poems” won the Andy Hope Literary Award, given by Cirque Press for its artistry.

The assembled poems, organized by title instead of theme, place or another traditional organizing principle, leap through time and space, connecting in unusual, startling and ultimately resonant ways. Many of them relate to Alaska and its exploration history, others to Vietnamese history and contemporary life. Gramse himself has spent time studying and teaching in Vietnam. Their forms are narrative, lyrical, dramatic and experimental, a rich mix.

In “Bering’s Hoard,” the voice of a crewmember on the St. Peter “conjures” an inventory of the nine sea chests brought aboard by Vitus Bering and then describes the melancholy Master, the landing and hasty retreat from Alaska, the shipwreck on the way back to Russia, and the hoards — that word again — of bold foxes that tormented the ill and dying men. “When the Master perished, we buried him nearby, clubs and axes in hand to keep the fox swarm at bay. Herds of sea cows slipped along slowly just offshore. In that same way, I died.” This poem fills two pages with solid blocks of lyrical text.

For that poem, the annotator references two real scholarly histories of Bering’s 1741 voyage to Alaska and notes that Bering did in fact bring nine chests aboard the ship and that no records exist of their contents. He also explains that the ancestors of the many foxes on Bering Island had been carried there on sea ice and were indeed a “scourge.” He then goes on to quote a long passage about the foxes from Georg Steller’s journal, as published in a 1925 book.

Another “historic” poem, “When Stalin Met Roosevelt in Fairbanks to Negotiate the End of WWII,” has “Soso” rising in the night from his lodging at Ladd Field to walk to a perimeter fence where he looked and listened as “kids were swimming in the river in front of their parents’ tents, in the light flickering curlicues on the water.”

In this case, the annotator explains that a Fairbanks meeting never happened, despite Roosevelt’s efforts to arrange one. Instead, he, Stalin and Churchill met in Tehran in 1943. Soso was Stalin’s childhood nickname, and Ladd Field, now part of Eielson Air Force Base, played a critical role in the Lend-Lease program that transferred aircraft to the Soviet Union during the war.

Poets often include notes to explain what might be obscure references in their poems, but the annotations here are more fun for what they imply about the annotator and his quest. He doesn’t always know what to make of a reference. “This poem seems to reference … “ At other times, he corrects errors. Sometimes he locates — and includes — photographs that authenticate images used in poems.

In one of the many poems with Vietnamese origins, “Last Day on Con Son,” the narrator and his friend, two Americans, are guided around the island to various sites including a cemetery where, at one grave, “shelves had been built … to hold the steady flow of combs, mirrors, white flowers of all kinds, paper purses with paper lipstick and a pretty paper brush.”The annotation for this one explains that the island, formerly a notorious prison island, is being redeveloped as a tropical vacation destination, and that the woman in the grave, executed in 1952 by the French as a teenager, is a national hero. A photo of her, Vo Thi Sau, is included.

Other poems lie closer to home for Alaskans, including “The Call,” in which the narrator and his daughter climb a mountain on Father’s Day, and “Edict,” in which the narrator lies in a tent beside an alpine lake, “listening to pebbles slide down the surrounding slopes,” waiting for something terrible to happen.

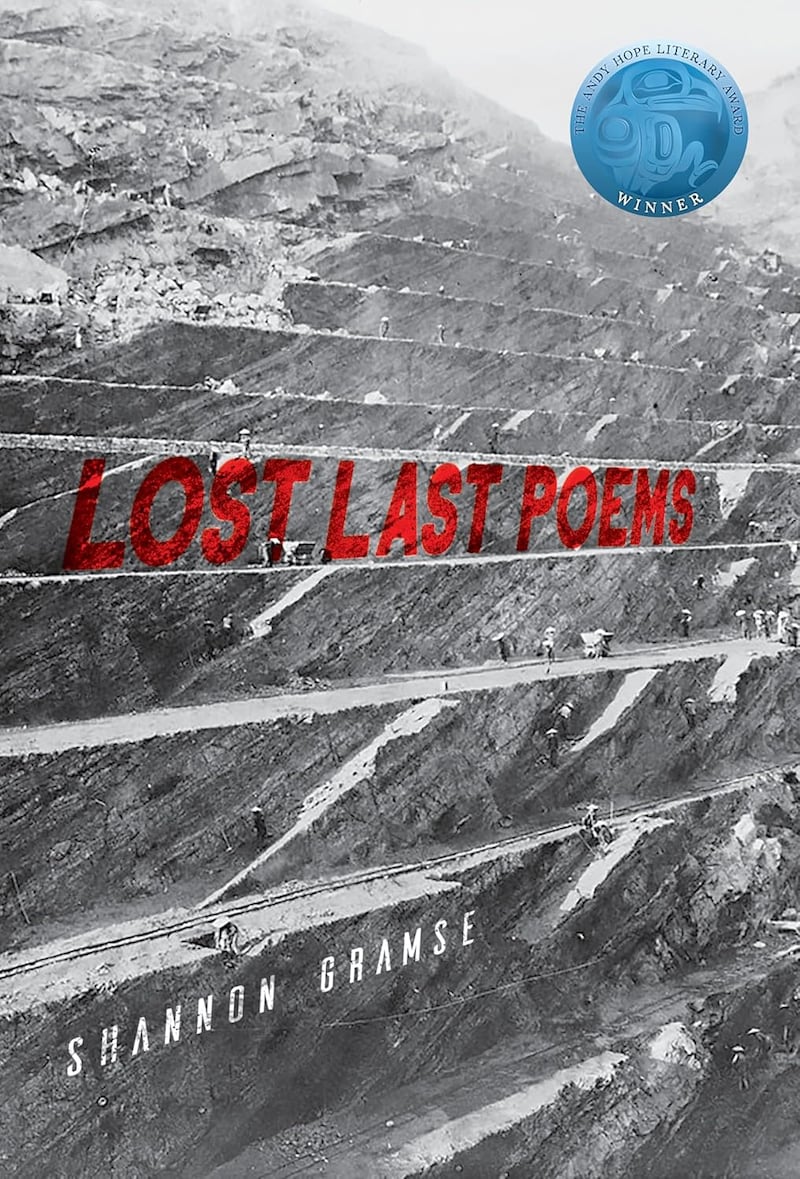

The black and white cover photos present another mystery for readers. The front photo is of a gigantic Vietnamese coal mine in the 1920s, with tiny laborers scattered across various ledges. The back cover is a photo of an oil rig in Katalla, Alaska, in 1922, with reflective water in front and snow-covered mountains behind. What is the relationship, to one another and to the poems? Readers, who may have noted the annotator’s introductory reference to “Late-Empire concerns,” will need to decide for themselves.

A gift, indeed — these poems presented to us by Shannon Gramse, a person of tremendous poetic, intellectual, humorous and empathetic reach. “Lost Last Poems” deserves to be found among the best of contemporary poetry.

[Review: Tom Sexton’s last poetry collection is a treasure]

[From fan fiction to fantasy books, Eagle River author Kellie Doherty thrives on world building]

[Book review: Anchorage man tells his story of redemption in memoir]