September 29, 2025• Physics 18, 164

Experiments at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider give the first hints of a critical point in the hot quark–gluon “soup” that is thought to have pervaded the infant Universe.

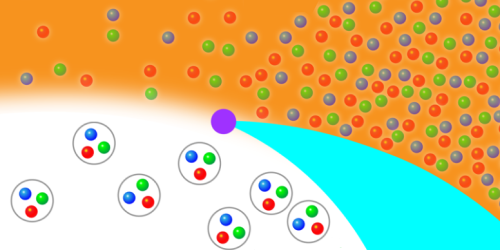

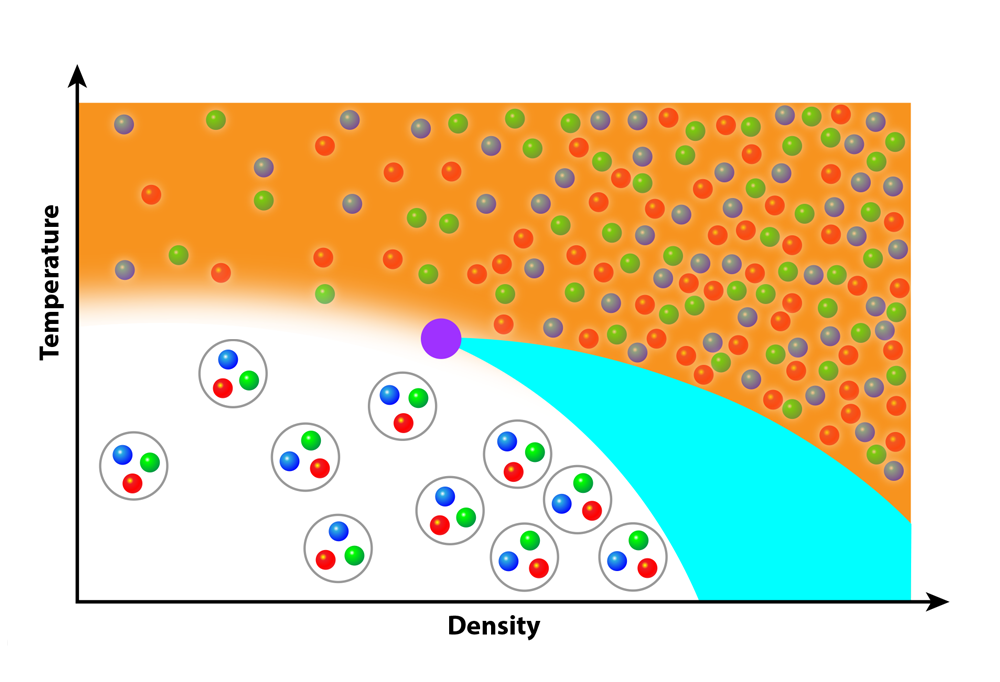

Figure 1: This schematic of the quantum chromodynamics phase diagram depicts how increasing the temperature can change a gas of bound quark particles (called hadrons) into a liquid-like quark–gluon plasma (shown as an orange “soup”). Heavy-ion collision experiments in the relevant energy range have detected hints of a critical point (purple dot), which would mark the edge of a first-order phase transition (blue arc) that extends up from the high-density, low-temperature region of the diagram.

Figure 1: This schematic of the quantum chromodynamics phase diagram depicts how increasing the temperature can change a gas of bound quark particles (called hadrons) into a liquid-like quark–gluon plasma (shown as an orange “soup”). Heavy-ion collision experiments in the relevant energy range have detected hints of a critical point (purple dot), which would mark the edge of a first-order phase transition (blue arc) that extends up from the high-density, low-temperature region of the diagram.×

The strongest force of nature—the one holding nuclear matter together—is described by the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD). The fundamental particles of QCD are quarks and gluons, which are normally bound within composite particles called hadrons—the most well-known of which are protons and neutrons. Only at extreme temperatures around 1012 K (a million times hotter than the core of the Sun) can quarks and gluons become deconfined, leading to a new phase of matter called the quark–gluon plasma. At vanishing densities, the transition between confined hadrons and the quark–gluon plasma is known to be ill-defined—happening across a wide range of temperatures rather than at a specific temperature. But theory predicts that at large densities and moderately high temperatures, a critical point exists, where the “fuzziness” disappears and a clear distinction can be made between the gas-like hadrons and the liquid-like quark–gluon mix [1–3]. New data from the STAR experiment at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York show what appears to be the first hints of this critical point (Fig. 1) [4]. If confirmed, such a landmark detection would provide an anchoring point from which further explorations of the quark–gluon plasma could venture, potentially offering insights into astrophysical phenomena like supernovae or binary neutron-star mergers.

The most familiar critical point is that of water. Under atmospheric pressure, water has three phases—solid, liquid, and vapor—which are separated by first-order phase transitions. However, if one heats and squeezes water to high-enough temperatures and pressures, it is no longer possible to easily distinguish the liquid and gas phases—such melding of phases is called a crossover. The critical point marks the boundary between this crossover and the first-order phase transition at lower temperature and pressure.

Critical points were first identified over 200 years ago by physicist Charles Cagniard de la Tour, and their striking properties have fascinated physicists ever since. Near a critical point, particles become correlated with their distant neighbors, causing large fluctuations in observable properties. For example, a droplet of water turns white at its critical point (so-called critical opalescence) because the long-range correlated particles cause photons to scatter more often in the material. The modern theoretical understanding of critical points was established by Kenneth Wilson, who was awarded the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physics for his theory of critical phenomena in connection with phase transitions.

The QCD critical point is especially interesting because—if observed—it would be the first critical point in a fundamental force of nature. What’s more, the observation of a sharp, nonambiguous transition between confined hadrons and deconfined quarks and gluons would help explain why quarks and gluons are never observed in isolation. This “confinement” puzzle is one of the Millennium Prize Problems selected by the Clay Mathematics Institute.

Measuring the QCD critical point has been challenging. For water and other condensed-matter systems, one can simply tune the parameters to reach a specific point in the phase diagram. But that’s not possible for quark–gluon matter. Instead, researchers must smash together heavy ions in colliders, creating short-lived, highly dense concentrations of matter that traverse the phase diagram as they expand and cool. By varying the beam energies, one can explore different regions of the phase diagram: Higher beam energies correspond to lower baryon densities, while lower beam energies probe higher baryon densities.

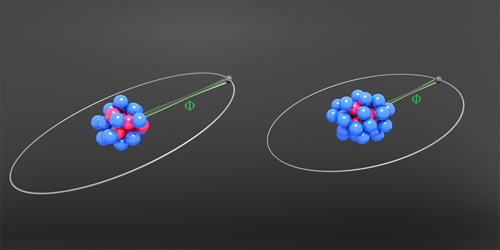

The STAR experiment is designed to sort through the debris from collisions at RHIC. In particular, the experiment’s detectors record the number of protons and the number of antiprotons that come out from each collision event. The net-proton yield, which is the difference between the proton and antiproton numbers, varies from event to event. The STAR Collaboration measures the net-proton distribution, whose “shape,” like that of other statistical distributions, is described by its mean, variance, and other so-called moments. The higher moments—in particular the fourth moment, or kurtosis—are sensitive to the growth of the correlation length at the critical point and are expected to show nonmonotonic behavior near a critical point [5].

In its hunt for the critical point, the STAR experiment performed a beam-energy scan to obtain data across a wide range of densities and then calculated the net-proton moments at each beam energy [4]. From the QCD equation of state (which describes the relationship between pressure and density), the moments are expected to remain constant or to monotonically decrease with increasing density. But if a critical point is present, the kurtosis could exhibit nonmonotonic behavior, including dips or peaks depending on the trajectory of the system in the phase diagram. The new STAR measurements revealed such a dip in the ratio of the fourth- to second-order moments (C4/C2) near a collision energy of 19.6 GeV. The size of the dip relative to experimental noise corresponds to a significance between 2 and 5 sigma (where 5 sigma would signify a detection) [6].

The dip in the kurtosis is qualitatively consistent with expectations of critical phenomena. If indeed the QCD critical point has been observed, the location of the point (below 20 GeV) would imply that that a first-order phase transition (like that between water and steam) occurs at high densities, which might be relevant to supernovae, binary neutron-star mergers, and other astrophysical phenomena.

However, it’s important to note that a dip is not a unique signature of the critical point: Dynamical effects such as baryon-number conservation [7] or nonequilibrium dynamics [8] can produce similar behavior. The observed minimum may also be sensitive to “freeze-out,” which is the reduction in particle interactions as the system expands and the particles end up too far from each other. The location of the freeze-out condition in the phase diagram can affect the appearance of the dip [9].

Although the new STAR experimental data are extremely exciting, their interpretation will require further theoretical and experimental progress. The incorporation of critical fluctuations into dynamical models such as relativistic viscous hydrodynamics is an ongoing effort [10]. The STAR Collaboration is still analyzing data from the Beam Energy Scan program, including fixed-target measurements at lower collision energies (3.0–7.7 GeV), which will probe even higher baryon densities. These future experimental results, combined with novel theoretical modeling, will be crucial for determining whether the observed nonmonotonic behavior indeed signals the presence of the QCD critical point.

ReferencesM. Stephanov et al., “Signatures of the tricritical point in QCD,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4816 (1998).V. A. Dexheimer and S. Schramm, “Novel approach to modeling hybrid stars,” Phys. Rev. C 81, 045201 (2010).M. Hippert et al., “Bayesian location of the QCD critical point from a holographic perspective,” Phys. Rev. D 110, 094006 (2024).B. E. Aboona et al. (STAR Collaboration), “Precision measurement of net-proton-number fluctuations in Au + Au collisions at RHIC,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 142301 (2025).M. A. Stephanov, “Non-Gaussian fluctuations near the QCD critical point,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 032301 (2009).V. Vovchenko et al., “Proton number cumulants and correlation functions in Au-Au collisions at sNN= 7.7–200 GeV from hydrodynamics,” Phys. Rev. C 105, 014904 (2022).P. Braun-Munzinger et al., “Relativistic nuclear collisions: Establishing a non-critical baseline for fluctuation measurements,” Nucl. Phys. A 1008, 122141 (2021).T. Dore et al., “Critical lensing and kurtosis near a critical point in the QCD phase diagram in and out of equilibrium,” Phys. Rev. D 106, 094024 (2022).D. Mroczek et al., “Quartic cumulant of baryon number in the presence of a QCD critical point,” Phys. Rev. C 103, 034901 (2021).X. An et al., “The BEST framework for the search for the QCD critical point and the chiral magnetic effect,” Nucl. Phys. A 1017, 122343 (2022).About the Author

Jacquelyn Noronha-Hostler is an associate professor in the Department of Physics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She earned her PhD from Goethe University in Germany. Her work explores the interface between the nearly perfect fluid obtained in heavy-ion collisions and the densest matter of the Universe found in the core of neutron stars. She received the 2018 Department of Energy Early Career Award and is an Alfred P. Sloan fellow. She was elected to the American Physical Society’s Division of Nuclear Physics Executive Committee and is in the leadership of both the MUSES and SURGE Collaborations.

Subject AreasRelated Articles Atomic and Molecular PhysicsSearching for a New ForceJune 10, 2025

Atomic and Molecular PhysicsSearching for a New ForceJune 10, 2025

A hypothetical fifth force could be detected by its effect on the optical transition frequencies of an element’s different isotopes. Read More »

Particles and FieldsPeering into ProtonsMay 22, 2025

Particles and FieldsPeering into ProtonsMay 22, 2025

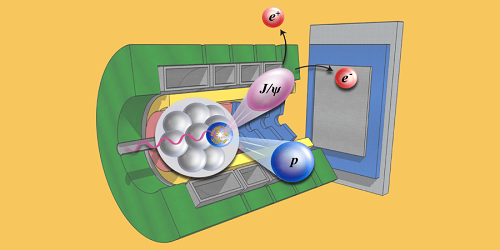

The internal structure of protons bound in nuclei has been probed by studying short-lived particles created when high-energy photons strike nuclei. Read More »