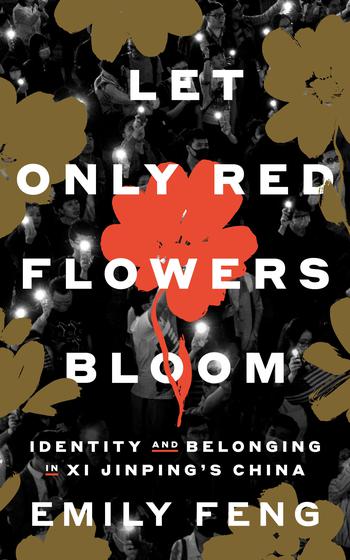

NPR reporter Emily Feng traveled back and forth documenting the stories in “Let Only Red Flowers Bloom: Identity and Belonging in Xi Jinping’s China,” until she was banned by Chinese authorities unhappy with her work. (Pixabay)

Ethnic minorities rooted out and sent to camps. Book sellers “disappeared,” or convicted of crimes against the state. Dissenters targeted and harassed, even in the United States.

This is life for the noncompliant, minorities and civil rights advocates in contemporary China according to “Let Only Red Flowers Bloom: Identity and Belonging in Xi Jinping’s China,” available recently from Penguin Random House.

NPR reporter Emily Feng traveled back and forth documenting the stories in “Red Flowers” until she was banned by Chinese authorities unhappy with her work. Her book takes China from the front page to the reader’s doorstep.

The title is a take on Mao Zedong’s exhortation in 1957 to “let 100 flowers blossom, and a hundred schools of thought contend,” to promote progress in the arts, sciences and “socialist culture.” Instead, the impetus for openness gave way within months to a backlash in which many critics were denounced and punished.

Feng starts her reporting with the story of a young prosecutor in the Chinese legal system, a woman fighting crime in an era in which China overhauled its judicial priorities to emphasize rule of law. The Chinese drew on examples from the West, specifically the U.S. and U.K. judicial systems.

Yang Bin, once a worker in a pesticide factory, found entry-level work in a prosecutor’s office and rose to become one herself. “Yang believed wholeheartedly n maintaining social order through a rigid application of the law, and she attacked her job with an activist’s zeal other bureaucrats found abrasive,” Feng writes.

Eventually Yang, disillusioned, pivots away from remorseless punishment toward justice for civil rights activists. Her advocacy elevates her to public prominence, and the attention of state security.

Yang’s story, like those of other ordinary people in the book, occupy a space between the final stage of communist China’s turn to nascent capitalism and the realignment to rigid social controls under Xi. The head-spinning feint would stand as interesting news on an inside page if not for China’s exaggerated response to resistance or individualism.

“Red Flowers” is populated by the defiant, the unwitting, and in the case of the “scooter thief,” the almost comical. Each of their stories is attended by shadowy security agents, digital surveillance, government pressure, arrests, threats and disappearances.

Emily Feng’s “Let Only Red Flowers Bloom” went on sale March 18, 2025. (Crown Publishing)

Their stories speak, among other themes, to an intolerance for anything beyond a form of nationalism that favors Han ethnicity and Mandarin language and seeks to homogenize the population accordingly.

In addition to human rights, Feng touches on business, religion, free speech and trafficking in women and girls as China reverses its One Child Policy to increase its population.

She also recaps and details China’s reneging on the One Country, Two Systems policy following the British handover of Hong Kong, and the resulting wave of protests, impressively well-orchestrated, that ended with a young generation fleeing the territory.

The story moves to Taiwan, to examine the complicated history there, and to the U.S., where Chinese authorities conspire to discredit and ruin a Chinese dissident artist.

Feng’s 304-page book is gripping, complicated and engaging, but also a thoroughly reported, relentless portrait of authoritarian rule.