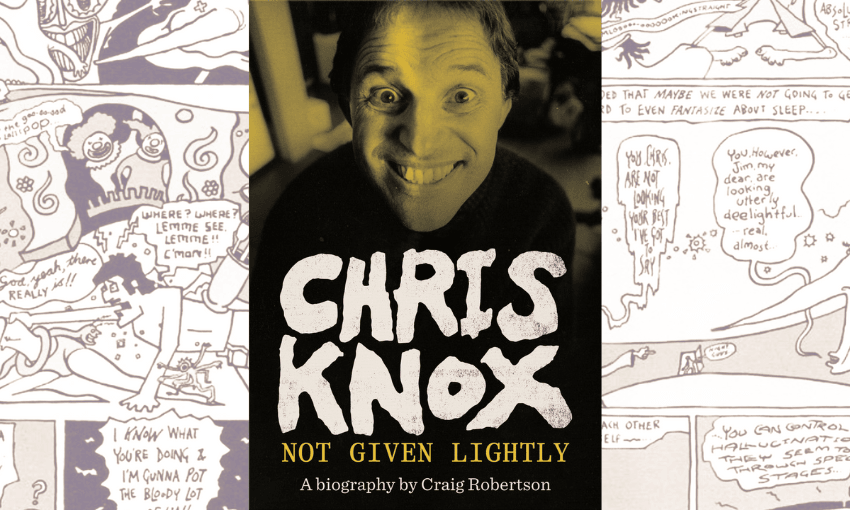

Claire Mabey reads Not Given Lightly, Craig Robertson’s long-awaited biography of iconic, contradictory artist Chris Knox.

Where do artists come from? What makes them? Why do they do it? These are questions central to Craig Robertson’s exhaustive, and at times exhausting, biography of musician, filmmaker, cartoonist, reviewer and TV presenter, Chris Knox.

Like most New Zealanders under 40 I was too young to follow the “Dunedin Sound” in real time. I came to it later, in compilation CDs and anthologies featuring musicians like Martin Phillipps, Hamish Kilgour and Chris Knox. ‘Not Given Lightly’ is a song I played over and over again in my last year of high school, before I went to study at Otago and got to experience the kind of heavy drinking and dingy living described in detail in Robertson’s study of Knox’s coming-of-punk-age.

Avid students of the Flying Nun subculture will be cringing at this amateur association. ‘Not Given Lightly’ was his mainstream hit and Knox was actively, aggressively about counterculture. Nevertheless, it’s that song – re-recorded to be used in an ad for Vogel’s bread in the 2000s – that many will associate with Knox and that lends this biography its name.

Not Given Lightly, the biography, is a fulsome, painstaking account of an art punk: an artist who “rejected mainstream New Zealand attitudes towards work” and made creativity central to life. Robertson (yes, brother of Grant) took 16 years to finish the book – greenlit by Knox just before he had a massive “left hemisphere cerebellar stroke” in 2009. Reading it, I had a dual and contradictory response: at times the book is so laden with minute chronology you feel the full weight of the research; and at other times it’s so breathless I willed it to slow and take a moment to linger on what is an emphatically fascinating, and influential life.

Robertson begins at the beginning: home town, parents, school. Knox grew up in Invercargill of the 1950s: a conservative New Zealand about a decade behind the rest of the world where art and culture was concerned. Knox was good at school – was good with words and with his friends started the Dim View newspaper, a satirical anti-authoritarian rag showing early signs of Knox’s signature aesthetic and anti-authoritarian sensibility. He loved The Beatles (Lennon over McCartney) and hated Bruce Springsteen so much he started writing his own, “better”, lyrics in response. But towards the end of his secondary school education he flailed badly, yet only one line in the book is given to the fact that his academic decline coincided with medication Knox started taking for epilepsy – drugs that gave him brain fog and that he later gave up.

Seizures punctuate Knox’s life. And an enduring interest in bodies: in their flaws and potential to express the grotesque remains part of Knox’s aesthetic to this day. Early in the book, Robertson describes Knox’s awe when Phil Judd temporarily becomes the bassist in Knox’s band The Enemy (which frankly sounded terrible but paved the way for the intermittently ingenious duo, Tall Dwarfs, with Alec Bathgate). Judd’s term was short-lived, however, in part because Knox didn’t like Judd’s process of rehearsing songs over and over again – Knox worried the repetition might bring on a seizure.

At this point I wanted Robertson to pause the freight train of recording detail and take a moment to consider how epilepsy may have shaped Knox’s frenetic art-making – an ethos of expressing, not perfecting. Knox’s approach to art is fast: he wrote fast, he recorded fast, he rarely laboured over a piece (excepting his cartoons, but even these were usually were filed weekly). For Knox, art is determinedly raw, handmade, flawed, monstrous (Matthew Bannister less generously described Knox’s style as “shambling amateurism”). I went back and watched the videos Knox made for Tall Dwarfs songs. They’re brilliant: small domestic films playing with animating inanimate objects, obscuring faces, upending normalities. There is something fascinating, here, about how fear of seizures (a fear that permeated lyrics over the years) and refusal of medicine-induced brain fog might have influenced a particular approach to getting art out of a mind and a body.

One of the revelations in the biography for me was just how much Knox influenced the early days of Flying Nun. That signature sound – like the band is in the room – came from Knox schlepping his four-track around houses to record bands like The Clean, The Chills and The Stones. During recording sessions he would offer direction, unafraid to say when songs might be going on too long, or were actually shit.

Knox was renowned for offering his opinion. His early, drug-and-drink-fuelled years in Dunedin saw him regularly kicked out of pubs like The Cook for belligerent behaviour, and his reputation for being a bully established. Knox strikes me as the kind of New Zealand man walking the line between superiority and inferiority complex: someone who thought he had better taste and superior interests to anyone caught up in mainstream, institutional dross; and someone desperate to make their mark, draw attention, be recognised; someone who greeted people by pinching their arses (a detail that riled me having had my arse pinched one too many times in The Cook in the early 2000s).

Robertson does alight, briefly, on what Knox’s life and relationships tell us about masculinity in Pākehā subcultures of the 70s, 80s and 90s. How excessive drinking (there’s a scene involving Colin Hogg and Knox spewing on, kissing and biting each other) and music were central to Knox’s male relationships. A kind of alternative intensity to, say, the sports enthusiasts – where instead of the rugby pitch, gig stages provided the ground upon which to throw egos about.

Over time, Knox mellows. He has a family and sees children as a way to channel attention away from his own ego. I enjoyed the descriptions of Knox and his partner and fellow artist Barbara Ward’s home in Hakanoa St, Grey Lynn, as a creative site: where their kids could paint on the walls and videos were filmed and new music made and recorded. There was no stopping art from being central to life. By the 90s Knox was earning decent enough money from reviews, columns and cartoons commissioned by mainstream media such as the Listener and NZ Herald that he was no longer eligible for the sickness benefit. Bigger money arrived in 2008 when Heineken used his song ‘It’s Love’ in an ad: $105,000.

The slow but sure embrace of Knox into the mainstream platforms is where I first encountered him away from his music: on the TV show New Artland, which he hosted. This is the New Zealand it’s been energising to be reminded of: a time when state broadcasters sought out and funded shows about artists – from the avant garde to the community based. Knox was a compelling host: at home among artists and participants doing wondrous acts together.

The biography stops in 2009, when the stroke tries to stop Knox. The best writing in the book is in the epilogue, where Robertson is fluid and unhampered by endless detail about who recorded what and when and with what tools. The epilogue paints a striking picture of an artist redefined by an injury that has left him with few of the words he was so deft at wielding; that has forced his daily life into routine; but who is still making art, relentlessly. I couldn’t help but think that in some, background way, Knox’s fascination with bodies, with making art with whatever, however may have prepared him for such a metamorphosis.

Robertson’s biography reveals just how much Aotearoa has changed over a few short decades. Knox was there, raging in the middle of some of those shifts: reacting against the popular culture, growing long hair then cutting it again in the 70s when everyone else had turned long hair into a trend. His artistry is there in the music – Tall Dwarfs made some great songs, some brilliant videos. The comics don’t do much for me but what is vital is the commitment to art, whatever the form that suited the expression Knox needed to put out there.

I had no idea he had contributed to bro’Town, or to Michael King’s Pākehā: A Search for Identity in New Zealand. Knox’s interactions with the new wave of groundbreaking artists and King’s excavations gave him an outlet to explore his growing appreciation of the legacy of colonisation: in 1990 he declined his nomination to receive the Commemoration Medal for Services to New Zealand.

After finishing Not Given Lightly I’m left in something like mourning: not for Knox, but for a media landscape that commissioned him to give (sometimes disastrous) opinions, honest reviews, and to make beautiful television about artists. I feel richer for having read Robertson’s passion project and while I wished at times for less of the weeds and a more panoramic view, the book (and its gorgeous design and strategically placed inserts) is a testament to the kind of self-belief that it takes to lead a creative life.

Chris Knox: Not Given Lightly a biography by Craig Robertson ($60, Auckland University Press) is available to purchase at Unity Books.