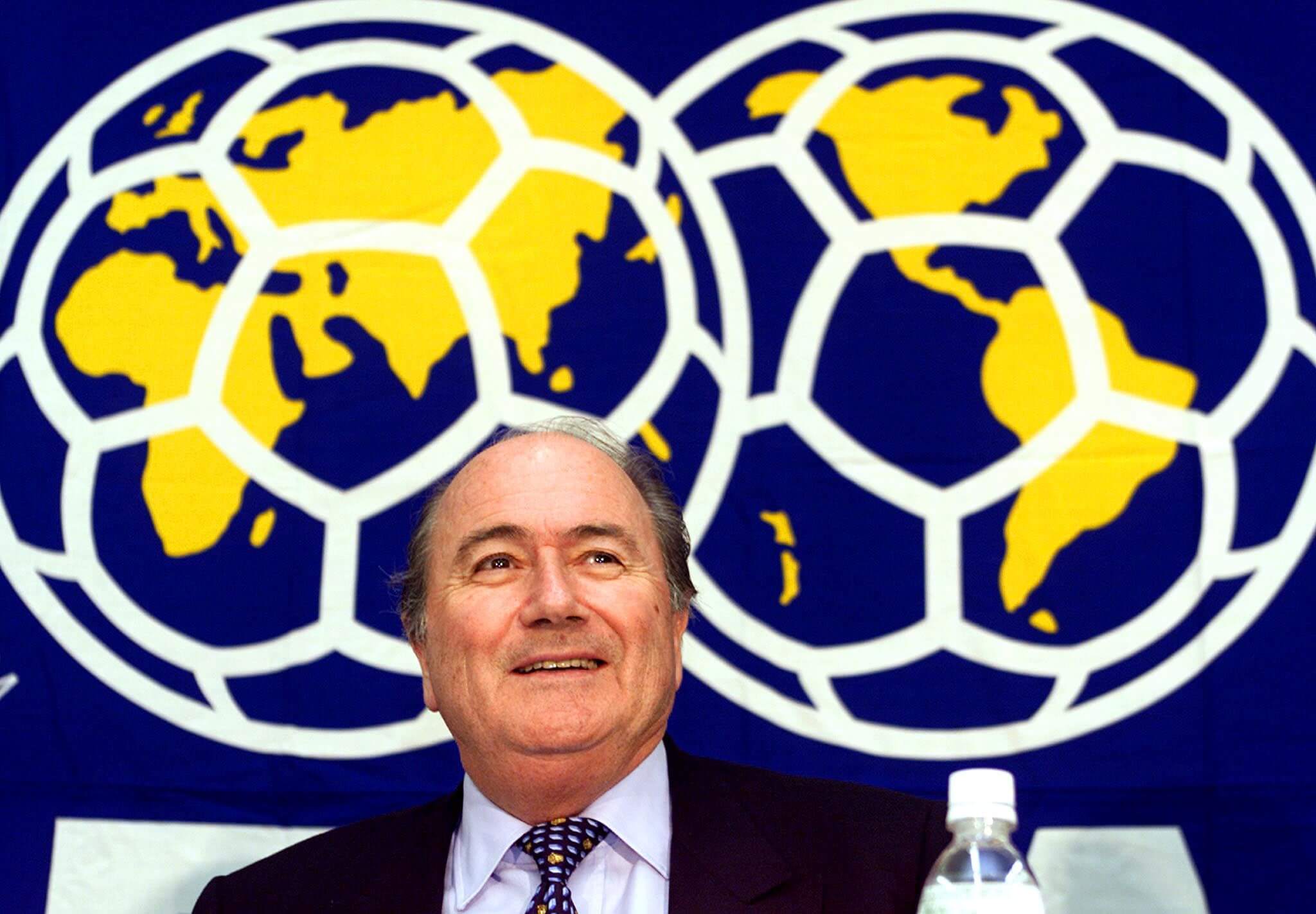

In 2000, World Soccer magazine commemorated the new century by interviewing FIFA president Sepp Blatter. One of the questions forced him to reach for his crystal ball: “What will the next 100 years bring?”

“I cannot look that far ahead,” Blatter replied. “I will go as far as 25 years, however.”

So what did Blatter predict?

“I will forecast no radical changes in that time,” he said.

Oh well.

Maybe Blatter was wise not to bother speculating about the future. After all, even repeating the consensus of the time is far from a surefire way of looking clever in 25 years, because various elements of the sport where there was a broad agreement about the direction of travel have proved misguided. Some of the things that felt sure about the 21st century have not materialised — at least, not yet…

Then FIFA president Sepp Blatter, pictured in November 2000 (Toru Yamanaka/AFP via Getty Images)

The European and South American duopoly will come to an end

In the same interview where Blatter didn’t quite make a prediction about the next 25 years, he said his proudest achievement during his time with FIFA was moving football away from being dominated by Europe and South America. The World Cup’s expansion from 24 to 32 teams for the 1998 tournament in France admitted more teams from other continents.

But the idea that the game’s superpowers are being challenged by outsiders is something of a myth. The nine current favourites to win next year’s World Cup (England, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain and Portugal from Europe, Argentina and Brazil from South America) were also the same nine favourites going into the 2006 edition.

Belgium and Uruguay, smaller countries from the same two continents, are the next most likely sides to triumph, according to the bookmakers. The biggest party poopers recently have been Croatia, another European nation who finished second and third at the World Cups in 2018 and 2022 respectively. But then, they also came third in that 1998 edition, so this wouldn’t have been a huge surprise at the turn of the century.

By now, we really expected things to be more different.

The Olympics’ men’s football tournament is rarely noteworthy, but Nigeria’s triumph in 1996, followed by Cameroon’s four years later, suggested African nations were set to become a serious force. Pele had famously declared a team from that continent would win the World Cup by the start of this century, which was, in fairness, nothing more than repeating the consensus from the time; then England manager Walter Winterbottom said the same in 1962.

Africa did finally get its first semi-finalists in 2022, when Morocco surprised everyone to reach the final four. But 14 of their 26 players were born outside the country; the majority in Western Europe. That doesn’t take anything away from their success, but it’s hardly evidence that Western Europe’s dominance is fading, and it isn’t a replicable template for most other African nations.

Morocco, in 2022, are the only African nation to reach the last four of the World Cup (Buda Mendes/Getty Images)

Granted, 2022 was a successful tournament for Africa, partly as they had such large numbers of supporters in Qatar, and the strength in depth across the continent means they will be the biggest beneficiaries of the World Cup’s expansion to 48 teams for 2026. But Nigeria and Cameroon — and for that matter, Ghana and Ivory Coast — have not become regular contenders as once hoped.

The other semi-finalists from outside Europe and South America were South Korea, on home soil in 2002; partly thanks to some charitable refereeing decisions, it must be said. But they haven’t won more than a single game at any of the five tournaments since. Other ‘outsiders’ who briefly flourished — Australia, Ghana, Japan, Mexico, Senegal — had a good generation of players rather than transforming into one of the elite.

It should be acknowledged that the women’s game is more geographically diverse. Even then, though, the most recent Women’s World Cup in 2023 produced, for the first time, a top three all from Europe.

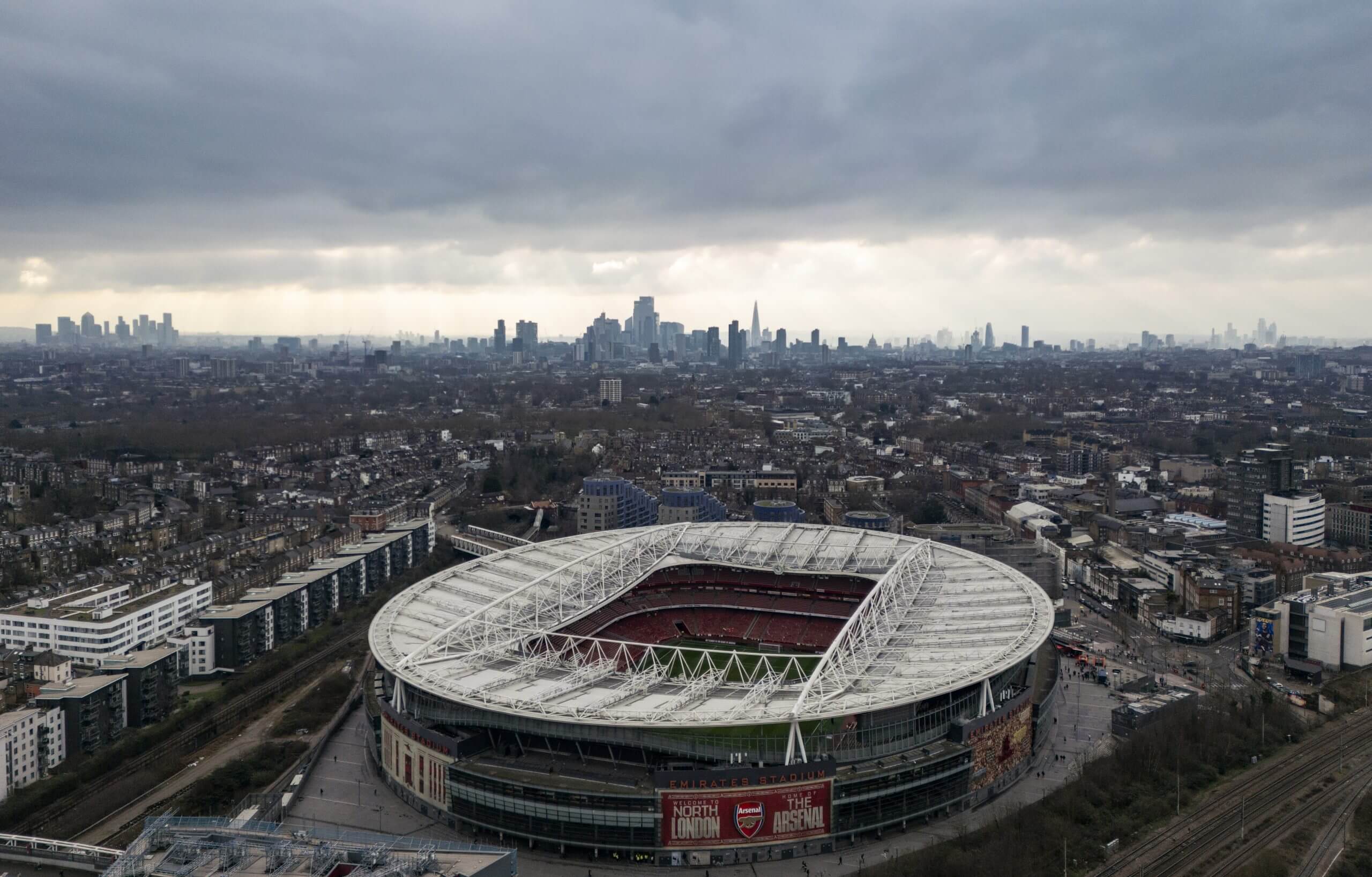

London clubs will move out of the city — and share grounds

This week’s news that Arsenal might play at Wembley while redeveloping the Emirates felt familiar to those who remember suggestions from around the turn of the century that the new Arsenal ground and the new Wembley might be the same project.

In the 1990s, the trend in English football was clubs selling their traditional home and building a modern replacement on the outskirts of town.

In an alternative history of London football, Arsenal have moved north, to Alexandra Palace, and Tottenham are even further into the suburbs in Enfield. Chelsea repeatedly flirted with the Battersea Power Station site, Brentford tried to move to Kingston upon Thames and Wimbledon effectively did go to Milton Keynes. But Wimbledon fans formed a new club who are now back playing at their spiritual home at Plough Lane, and barring Chelsea, the others have — remarkably, in such a congested city — all found land to build new grounds within the boundaries of their rightful patch.

A related suggestion was that more English clubs would groundshare. The idea that England, Arsenal, Tottenham and West Ham United would all move to 60,000-plus capacity new grounds in the space of 13 years felt distinctly unlikely. The common line was that we needed to look to the continent: Juventus and Torino in Turin, and Roma and Lazio in Rome, and Inter and Milan, and Bayern and 1860 in Munich all shared at the time, and it worked for them, so why shouldn’t it work for us?

Arsenal are one of several London clubs who have built new stadia since 2000 (Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

What we didn’t fully appreciate was that, in various ways, it didn’t work for them. And the same hasn’t happened in England. English clubs have retained their identity, their geography and, less glamorously, their financial stability and earning power by owning their own grounds outright (with the exception of West Ham, whose fans are the unhappiest at their team’s new home). Juventus, meanwhile, moved into their new English-style 41,000 capacity stadium in 2011, and don’t share it with Torino.

But let’s not forget that the FA had indicated it was open to Arsenal or Tottenham — or both — playing at Wembley permanently. David Dein, who held lofty positions with both Arsenal and the FA, was seemingly keen, but the club’s then manager Arsene Wenger was strongly against it. Furthermore, Spurs’ chairman at the time Daniel Levy refused to rule out a groundshare with Arsenal when both were planning to build new grounds.

Today, while there have been various groundshare agreements over the years, the 92 clubs that comprise the four tiers of the Premier League and EFL play at 92 different grounds.

More players will retire early from international duty

The explosion in wages towards the end of the 20th century meant players were desperate to squeeze another couple of years out of their club career. They could earn in a single season what had previously taken five. One way to make this viable, it seemed, was by retiring from international duty to focus on your club.

This wasn’t an entirely new concept, of course, but Euro 2000 seemed a prescient example. Alan Shearer and Dennis Bergkamp, two of the most prominent Premier League forwards of the time, stood down from international duty after that tournament. Shearer was only 29, Bergkamp was 31, and both played on, for Newcastle and Arsenal respectively, for another six years. The more money in club football, the more players would prioritise it from a relatively early stage, right?

But maybe wages are now so high throughout a player’s career — and there are more options abroad for one final payday — that this isn’t as relevant today. OK, players still step back from international duty in their mid-thirties, or when they’re no longer a regular, going out on their own terms, and you do get the odd surprise early retirement, but go back to the Ballon d’Or voting from a decade ago, look through the names. Not only have none retired from international football particularly early, but the ones who did give it up — Lionel Messi, Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Toni Kroos — reversed their decision and came back to it anyway.

Football is increasingly focused on the club game, but players — particularly those who have spent much of their career abroad — still have a deep affection for representing their nation.

Cristiano Ronaldo is still playing for Portugal at the age of 40 (Attila Kisbenedek/AFP via Getty Images)

Midfield will be about physical rather than technical play

Well, a mixed bag, this one. But the consensus at the turn of the century was that the game would become increasingly physical in the centre of the pitch. The pretty playmakers, particularly those deep in midfield, would be overpowered by athletic destroyers and box-to-box runners. Arsenal’s Patrick Vieira, an excellent technician but also a huge physical presence, was considered the prototype for future midfielders.

“I haven’t changed,” said Pep Guardiola, then near the end of his playing career as a midfielder for Barcelona, Spain and others, in a 2004 interview with The Times. “My skills haven’t declined. It’s just that football now is different. It’s played at a higher pace, and it’s a lot more physical. The tactics are different, too. To play just in front of the back four now, you have to be a ball-winner, a tackler, like Vieira or Edgar Davids.

“If you can pass too, well, that’s a bonus. But the emphasis, as far as central midfielders are concerned, is all on defensive work.”

Pep Guardiola alongside Marcel Desailly in 2004 (Karim Jaafar/AFP via Getty Images)

Top-level football seems to have become more physical in the past few years, and midfield has, to a certain extent, become about power again, partly due to the emphasis on pressing.

So perhaps a 2025 midfield wouldn’t look entirely shocking by the expectations of 2000, but there was a period in between, when both club and international football were dominated by the Spanish trio of Sergio Busquets, Xavi and Andres Iniesta, whose rise was partly due to Guardiola’s management. The fact that Andrea Pirlo, a converted No 10, and the evergreen Luka Modric have exerted such a dominance on European football this century demonstrates that it certainly hasn’t all been about physicality and defensive qualities.

The United States will produce world-class players

Perhaps the most universal ‘prediction’ towards the end of the 20th century was that the United States men’s team would become a serious footballing force in the 21st century.

Their successful hosting of World Cup 1994, combined with their professional league and their track-record of dominance in other sports, seemed a surefire recipe for serious progress.

If you’d told an average football supporter in 2000 that the U.S. would be the main host nation of World Cup 2026, most would have guessed they’d be a serious contender to win it. If you’d said they’d miss out on World Cup 2018 due to finishing behind Panama in qualification, you’d have been laughed out of town. The precise mechanics now accepted as holding back player development in the States — the pay-to-play model at youth level, the limitations of MLS — were not really considered.

After all, serious progress seemed to have been made as early as World Cup 2002, when the USMNT defeated Portugal and Mexico and reached the quarter-finals, where they lost only 1-0 to eventual runners-up Germany. Soon after, they appeared to have produced their first world-beater. “Freddy Adu, Still Only 13, Already Plays Like a Man” read The New York Times’ headline in 2003. But Adu never played in a World Cup.

Freddy Adu, pictured in 2004 (Robert Laberge/Getty Images)

To this day, no American man has received a single vote in the Ballon d’Or. By way of contrast, recent years have seen footballers from the likes of Georgia, Guinea and Slovenia finish in its top 20. Christian Pulisic isn’t far off that level. After two seasons and 20 Serie A goal contributions for Milan, he may peak perfectly, at age 27, for next year’s World Cup on home soil.

Perhaps most surprising is that even their production of top-class goalkeepers seems to have dried up. This was always the strong suit of the U.S. — the typical explanation was that American kids grew up playing sports where they used their hands, not their feet. Zack Steffen and Matt Turner are decent but haven’t enjoyed the prominence of Brad Friedel or Tim Howard, who both rank in the top 50 players in terms of all-time Premier League appearances.

All major new stadiums would have a closeable roof

When it opened in 1996, Ajax’s Amsterdam ArenA — now named the Johan Cruyff ArenA — featured a fully-retractable roof. It was the first European football stadium with that feature.

Shortly afterwards, also in the Netherlands, Vitesse Arnhem built something similar. And when Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium opened in time for the rugby union World Cup of 1999 — and subsequently hosted domestic cup and play-off finals during Wembley’s reconstruction period — it became the largest football stadium in Europe with a fully-retractable roof. It seemed that would become standard, and Japan took things further with the Sapporo Dome, built for World Cup 2002, which was a permanent indoor arena with a natural grass pitch which slid in from outside for matches.

Yet such features remain novelties today; the cost of installing a full roof is considerable, and most clubs have decided it’s simply not worthwhile. There are some exceptions around Europe, mainly in the north of the continent, where the harsher winter climate lends itself more to indoor sports: Stockholm in Sweden is the only European city with two venues like this. Denmark’s Copenhagen and Saint Petersburg in Russia also have stadia that can be covered. Germany has three where the roof can be closed, in Frankfurt, Dusseldorf and Gelsenkirchen, and there are similar grounds in Lille (France), Bucharest (Romania) and Warsaw (Poland). The most striking addition to the list is the remodelled Bernabeu in Spain’s capital Madrid.

But no stadium in England has a complete either fixed or closable roof; Wembley’s extends only far enough to cover the stands, rather than the pitch. The atmosphere under the roof in Cardiff for big Wales rugby matches remains — in British sport at least — entirely unique.

English football’s newest ground, Everton’s Hill Dickinson Stadium, does not have a full-cover roof (Getty Images)

Pay-per-view will dominate British television coverage of football

Pay-per-view television was all the rage at the turn of the century, and was evidently proving successful in boxing. So, in 1999, English football tentatively dipped its toes into the water. The first pay-per-view game was, somewhat improbably, a second-tier fixture between Oxford United and Sunderland.

“The idea is by no means revolutionary. But the impact on football may well be,” reported the BBC at the time. “If it is proved that viewers are also prepared to pay extra to watch chosen Nationwide League games, then — like it or not — pay-per-view could well become enshrined as part of the national culture, as it is in the United States.”

The Premier League got involved from 2001, launching Premiership Plus — later PremPlus — with one match a week on a pay-per-view basis on Sundays at 2pm. It lasted for six years, and was broadly successful, partly because fans could buy a ‘season ticket’ package up front for all 40 games each season, meaning it literally wasn’t pay-per-view if you were happy to stump up in advance. But competition law meant Sky, which controlled the channel, had to stop buying up all the Premier League’s television packages, and the operation ceased in 2007.

We didn’t hear much more about pay-per-view until the 2020-21 pandemic-affected, behind-closed-doors Premier League campaign, when the television companies attempted to charge fans £15 to watch the ‘additional’ matches that weren’t selected for the usual coverage. Those games attracted an average of 40,000 paying customers, but the scheme prompted an enormous backlash, with some fan groups campaigning to raise money for charity instead. The concept was scrapped.

Premier League chief executive Richard Scudamore, in 2000, announcing BSkyB’s successful retention of TV rights to screen live matches (Peter Jordan/PA Images via Getty Images)

Incidentally, former Milan president, Italian prime minister and media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi once suggested that pay-per-view would become such a fundamental part of football that match-going supporters would be allowed free entry to grounds, in order to generate the atmosphere for paying television viewers. With season-ticket prices rising every year, that feels like a particularly bad prediction.

In general, considering technological developments and the brief experience of every Premier League match being available due to Covid-19, it seems improbable that the ‘traditional’ model of television subscriptions remains in place. Sky still dominates, and the basic structure is still about monthly subscriptions. For now, at least.

Fewer top managers will be former players

At the turn of the century, it was clear football was becoming more sophisticated, more technocratic, more based around sports-science. And therefore, it seemed likely there would be a boom in the number of top-level managers who had no serious playing career. As the legendary Italian coach Arrigo Sacchi famously said, “I never realised that to be a jockey, you had to be a horse first.”

Arsene Wenger was often cited as the model for future managers. It’s worth clarifying that Wenger had a reasonable playing career, including a small contribution to Strasbourg winning the French title in 1979, but he simply didn’t feel like an ex-pro. He felt more like an academic. And when Wenger’s position in the English game was challenged by the arrivals of Jose Mourinho and Rafa Benitez in 2004 — neither of whom had enjoyed a top-flight playing career — it felt like the start of a revolution.

But only five of the current 20 Premier League managers/head coaches — Fabian Hurzeler, Thomas Frank, Daniel Farke, Eddie Howe and Vitor Pereira — didn’t play top-flight football. In contrast, six of them played at international level.

Rafa Benitez and Jose Mourinho didn’t usher in an era of ‘outsider’ head coaches (Odd Andersen/AFP via Getty Images)

And while there are some notable exceptions, most of the managers who have dominated European football in the past decade or so — Guardiola, Antonio Conte, Zinedine Zidane, Didier Deschamps, Carlo Ancelotti, Luis Enrique, Diego Simeone, Roberto Mancini — were highly prominent players, regularly turning out for the world’s best national sides. Even Hansi Flick, whose playing career sometimes goes under the radar, appeared in a European Cup final for Bayern.

People always seem to think the next generation will be different. But younger coaches in charge of Europe’s major clubs today — Xabi Alonso, Mikel Arteta, Enzo Maresca, Igor Tudor, Cristian Chivu, John Heitinga, Ruben Amorim — are all familiar names from their playing days a decade or so ago.

Granted, almost by definition, the ‘outsiders’ take longer to reach the top, such as Maurizio Sarri. But the anticipated shift towards non-players has, a little surprisingly, not occurred.