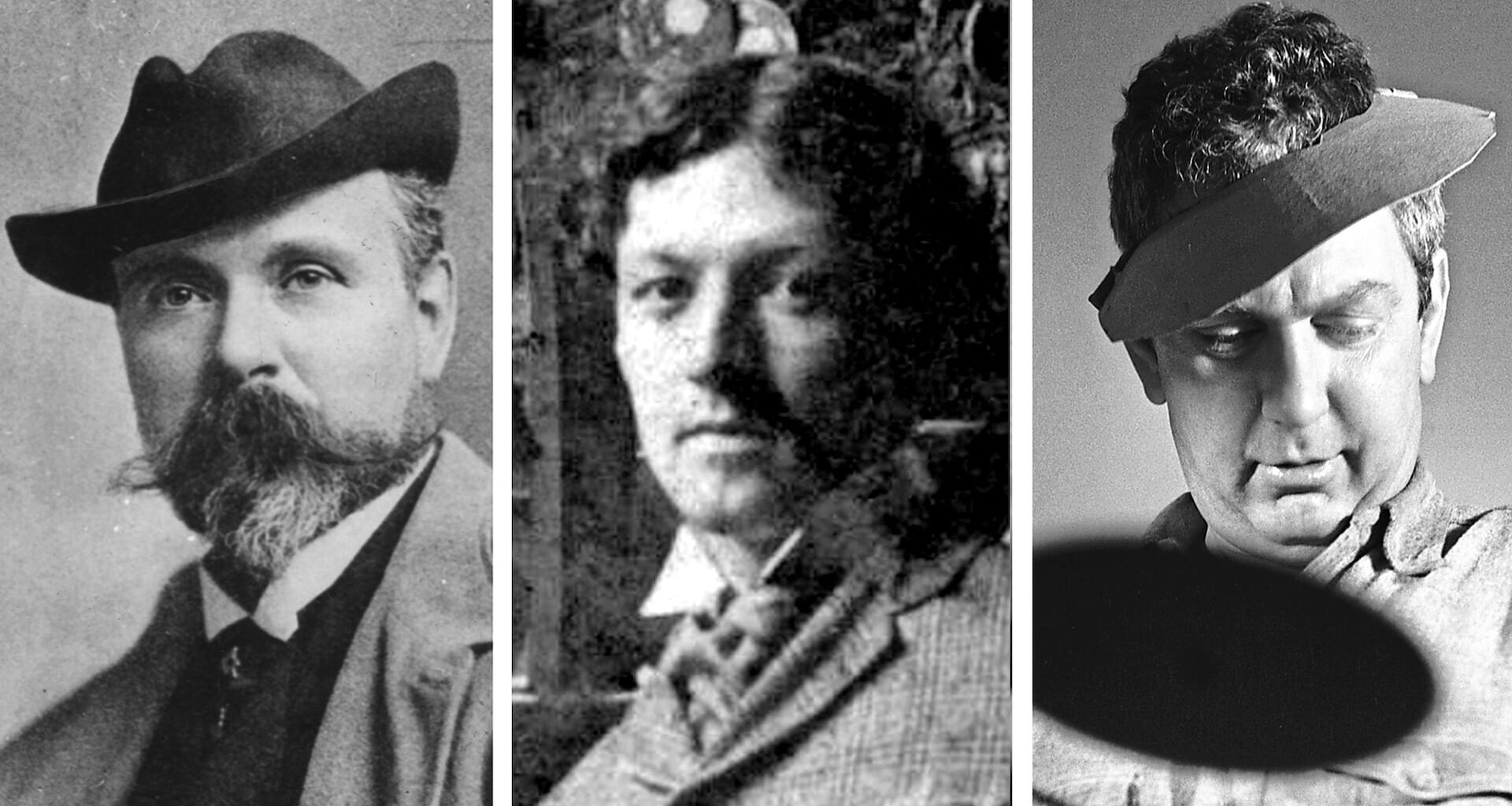

For more than quarter century, Greta Greenberger ended her tours of Philadelphia City Hall at the tower, just below the bronze buckled shoes of William Penn (1892), the shady colossus that Alexander Milne Calder sculpted.

From there, she’d point up the Parkway to Logan Square, where on hot days children sneak into The Fountain of Three Rivers (1924), created by Calder’s son, Alexander Stirling Calder, to honor the Schuylkill, the Delaware, and the Wissahickon.

She’d finish her lesson at the Philadelphia Art Museum, where an unearthly, white mobile, Ghost (1964), designed by the third generation of Alexander Calders, Sandy, sways ever so slightly in the Great Stair Hall.

“Sometimes, I’d refer to this as ‘The Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost,’” she says. “It tells such a wonderful story.”

That story will be easier to tell now, with the opening of Calder Gardens at 21st Street and the Ben Franklin Parkway. The Gardens, focused on the work of the youngest Calder, known as Sandy, brings another opportunity to celebrate the family dynasty’s in Philadelphia: three sculptors named Alexander Calder who have shaped the look of the city and beyond.

“The Calder family is incredibly important to Philadelphia,” said Anna O. Marley, the former chief curator at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), where so many Calders studied. “They tell us so much about what it means to be an artist in the United States and how an American artistic identify was created in Philadelphia.”

And their work here offers “a pocket history of art,” in the view of Kathleen A. Foster, the Art Museum’s senior curator of American art.

“Between the three of them, you really go from the academic realism of the grandfather through kind of shift into Art Deco and modernism in the `20s with Stirling Calder, and then all the way into modern forms, completely abstract shapes and bright colors.”

‘One of the greatest’

The Philadelphia that Alexander Milne Calder, a Scottish stonecutter’s son from Aberdeen, first saw in 1868 was sorely in need of a makeover. The sprawling metropolis was known for building big things like ships and rail engines and a wealth of small manufacturers that earned it the nickname “Workshop of the World.”

“It’s clear that there is no future for a city that is just increasingly based on its industrial might, on the dirt-producing, noise-producing, the squalor,“ says David Brownlee, emeritus professor of the history of art at the University of Pennsylvania.

The boundaries of Fairmount Park had just been established the year before and plans would soon begin for a giant celebration of the country’s 100th birthday, the 1876 Centennial, which would show the world the city’s cultural achievements. The Benjamin Franklin Parkway was unfolding, a broad boulevard lined by art and leading to what Brownlee calls “one of the greatest monumental ensembles of sculpture ever created.”

That would be City Hall, the émigré Calder’s workplace for 22 years as he presided over the creation of more than 250 sculptures from his first floor office in the building’s southwest corner — and the towering figure of the colony’s founder.

Calder had worked at the Royal Academy in Edinburgh and on the Albert Memorial in London before sailing to America. He stopped in New York, but chose Philadelphia, armed with a letter of introduction to the city’s most eminent sculptor, Joseph A. Bailly, and to the scion of a monument business, William Struthers. Calder was 22.

He registered that year at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the nation’s first art school and museum, and studied “antiques,” drawing from plaster casts of classic sculptures. It was not long before Calder won a prized commission over one of his instructors, to sculpt the likeness of Major Gen. George G. Meade atop his horse, Baldy. Meade, who’d defeated Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg, later designed many of the paths and drives of Fairmount Park. His statue stands now behind the Please Touch Museum on Lansdowne Drive.

When Greenberger gives tours of City Hall — though retired, she still volunteers one day a week — she likes to start in the north portico, where one can sample his expansive vision. Look up to the south, and there are Africans, surrounded by tobacco leaves, a lion. To the east, people from China, Japan, India, and an Asian elephant. West are the Native Americans and pioneers, and a bear. And north is Europe, people from Germany, England, France, maple leaves, and cattle. (She isn’t sure why cattle.)

Calder started on the Penn sculpture in 1886. The iconic figure, now visible from miles away, was the fourth version of the colony’s founder that the sculptor created. Calder’s models were one-tenth the size of the 37-foot high statue. His goal, according to an article at the time in The Inquirer, was to create “William Penn as he is known to Philadelphians; not a theoretical one or a fine English gentleman.”

Four teams of horses drew massive plaster sections of the statue up Broad Street to the Tacony Iron & Metal Works. It wasn’t until Thanksgiving 1894 that the head was lifted onto the statue atop the tower, completing Calder’s colossus.

He was not happy with the result.

For most of the day, William Penn’s face is shadowed. That was not the artist’s intent. Calder had wanted Penn facing south, where the sun would light his youthful face and the intricate detail of his garb would be visible for all to admire.

But members of the Public Buildings Commission wanted Penn facing northeast, toward Penn Treaty Park, the site of the 1683 peace agreement with the Lenni-Lenape.

In a letter quoted in the Dec. 14, 1894 Inquirer, Calder wrote “I think that you will agree that is very disappointing from every point of view.”

While Calder lived in a number of homes around the city — a home at 2020 Bainbridge St. and a studio at 337 Broad. When he registered at PAFA, the address listed was 1903 N. Park Ave., now on Temple’s campus. Decades later, his granddaughter, Margaret Calder Hayes, would remember the North Philadelphia house as “gloomy” — four floors with Empire furniture, a long dark hallway leading to a parlor where children were not welcome unaccompanied.

Calder had met his wife, the Glasgow-born Margaret Milne soon after his arrival in Philadelphia and married her after a brief courtship.

Three of their sons would study at PAFA and become artists — Ralph Milne Calder, and Norman Day Calder, and Alexander Stirling Calder, but it was “Stirling,” the eldest who left the biggest mark on Philadelphia.

‘An idealist, somewhat withdrawn’

In a remembrance kept in the PAFA archives, Alexander Stirling Calder describes art as a fallback. Ever since he was 6 and saw the great Edwin Booth play Hamlet, Stirling Calder wanted to be an actor. But he was too shy. In 1885, he enrolled in art classes at the academy’s new building at Broad and Cherry, and years later recalled the first criticism of his teacher, the artist Thomas Eakins: “Attack all of your difficulties at once.” Eakins urged sculptors to paint, painters to sculpt, and to dissect cadavers to learn anatomy.

After studying at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he returned home and won a commission to immortalize Samuel Gross with a statue that first stood on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (It’s since been moved to the Center City campus of Thomas Jefferson University). At 25, he married a fellow PAFA student, Nanette Lederer, a painter.

To the critic Malcolm Cowley, Stirling Calder was “an idealist, somewhat withdrawn, wholly impractical, creating symbolic figures while brooding on the cruelty of nature.”

Foster says that looking at the allegorical figures in Logan Square’s Swann Fountain, you can see how Stirling inherited his father’s traditions.

“But the figures have a kind of sleek, modern simplicity to them,” she said. “They’re more stylized. So by the 1920s the Swann Fountain represents a kind of moving from the academic past into a more expressive and abstract style.”

The fence came off the Swann Fountain on a hot July day in 1924. The next evening, 10,000 revelers danced to tangos from a police band. Not everyone was pleased — some wondering if the average Philadelphian would grasp the significance of all that Calder had created.

“The meaning of works of art is just as mysterious as life itself. It can be explained in many ways by people of different philosophies. …,” he was quoted in the Evening Bulletin as saying. “There are lots of things in life we do not understand; art is no exception.”

In his autobiography, Sandy Calder included a photograph of the sprawling mansion in Philadelphia where he says he was born. He called the place Lawnton. In 1898 when Calder was born, Lawnton was a neighborhood in East Oak Lane, served by the Reading Line and lined with grand homes where the wealthy went to escape the summer heat.

It’s unlikely Calder was born there. David Brownlee has dug into the mystery of the third and most famous Calder’s birthplace. While his family doctor lived in Lawnton, and it is possible that his mother delivered her son nearby, more likely, he was born near the edge of the growing city, at 1203 East Washington Lane in Germantown. City records showed that Stirling Calder rented that country place, while the family still owned a home on North Park Avenue.

In Margaret Calder Hayes’ memoir, she described how Sandy, two years younger, went to school in Buster Brown suits his mother had sewn and by 8 had built a Noah’s Ark of animals. He enrolled in Germantown Academy, when it was still in the city, but left at age 9 before moving to Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y.

“We love to claim him, but he only went to school here as a child,” Foster said of the youngest Calder’s time in Philadelphia.

Yet in some ways, he’s the essence of the city he was born in: practical, playful, unpretentious, no pushover.

He worked as a fireman on a steamer bound for San Francisco, spent a year keeping time in a Washington state logging camp. Trained as an mechanical engineer, he moved to New York City at age 25 to paint.

He is known as a 20th century modernist, the artist who put sculpture in motion.

After visiting Calder’s Paris studio in 1931 and marveling at his sculptures that relied on little motors, Marcel Duchamp coined the word “mobiles” for these kinetic marvels.

Parisians took to him, while they scoffed at other American artists. Cowley, in an introduction to Hayes’ Three Alexander Calders had a theory:

”Of course his work in itself, continually inventive, playful, and enchanting, was his ticket of admission.” But Sandy and his wife Louisa, “a beauty,” Cowley wrote, entertained generously and simply. Calder was in the tradition of the Noble Savage, “who disregards social conventions and judges everything by his instinctive standards.”

“A big child,” as his friend the playwright Arthur Miller once put it.

Sandy Calder created Ghost in 1964 for a retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York City, that included 400 examples of his mobiles, stabiles, toys, jewelry, carvings, tapestries, etc. The Art Museum bought the 34-foot-long showpiece a year later and brought it to the city of his birth.

“It’s a colossal example of the mobile and it’s majestic,” Foster said. “When it moves, it’s just breathtaking, because it, it almost moves like a giant dinosaur or something. In other words, it’s got long spines and fins, and it moves very slowly and grandly in the air currents in the Great Stair Hall. … It’s delightful.”

“When every baby has a mobile hanging over their crib, you don’t think about Calder as being the genesis of this. I think he would be delighted to know that … because he was such a child at heart. He managed to keep that imagination.”

Now, Philadelphia will be home to an institution that celebrates that imagination. It’s a fitting homecoming for an artist whose life and legacy was so shaped by his family, who in turn both shaped and were shaped by Philadelphia.

Tú Huynh was working at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., when he told a job applicant to look for him under the giant Calder mobile that hangs in the East Building.

That was in 1997. The applicant, Kaleo Bird, landed the job — and later, his heart. Three years later they moved as a couple to Philadelphia, where she started grad school. Soon they married.

In 2008, when their son was born, they didn’t take long to decide on a first name:

He’s now 17, a senior at Penn Charter School.

“I have yet to meet anyone my age who knows who the whole Calder family was, which is a shame because I feel they’ve had such an impact here, particularly with City Hall,” said the teen. “So many people think Ben Franklin is atop City Hall and don’t know anything about these beautiful sculpture.”

His father now runs the Art in City Hall program.

“I tell people that the true art of City Hall belongs to Alexander Milne Calder,” says Tú Huynh. “This was his Sistine Chapel. There are over 250 sculptures, leafs, busts all over this building. And that’s an homage to his ideal of what this city, state and country is supposed to be about. And he doesn’t sugarcoat anything. There are enslaved Africans, Indigenous populations, Europeans. It tells you the folks who’ve contributed to this extraordinary country.”

Calder Huynh says he feels the weight of his name — in a way that the two generations named after Alexander Milne Calder must have felt.

He paints, draws in charcoal, creates his own comic books — exploring themes with super heroes and Westerns, always with an eye on his father’s works that line the walls of their home.

“Naming me after them is such a big thing to put on someone. For me, it is a weight that Alexander Sandy Calder must have felt. A weight to achieve and create something that differs from what his family members had created, which is kind of cool. … Put something in this world that hasn’t been done yet.”

“The Magic of Calder Gardens” is produced with support from Lisa D. Kabnick and John H. McFadden. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.

To support The Inquirer’s High-Impact Journalism Fund, visit Inquirer.com/giving