In response to President Trump’s “tariff war,” Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum’s economic team recently presented a draft decree that would apply 1,400 new tariffs of up to 50 percent on purchases from China. These drastic measures reflect the intense pressure on Mexico to meet US demands of limiting the role of China in Mexico’s foreign trade. The US remains the largest market for Mexican goods, and exclusion would have severe consequences for Mexico’s economy.

The Trump tariffs are the latest iteration in America’s “security-shoring” strategy, which subordinates trade relations to US national security interests. The Biden administration initially defined this strategy with three pillars: investment in strategic sectors; alignment with allied countries; competition with China in technological areas such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and quantum technologies. Through security-shoring, the US has attempted to pressure trade partners to limit ties to China, placing third countries in a difficult position. Mexico must navigate complex relationships with its two most important trading partners, the two largest economies in the world. This formulation is what I refer to as “new triangular relations” between Mexico, the US, and China.

The Mexican position is unique. Mexico has long maintained a deep political and economic relationship with the United States, holding stronger bilateral ties to the US than other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The past twenty years have also seen a growing presence of Chinese imports and foreign direct investment (FDI), which are now essential for the functioning of the Mexican economy. These two trade relationships are closely linked: Chinese imports serve as essential inputs to the production of Mexican goods, the majority of which are then exported to the US.

These new triangular relations have emerged from the recent process of “globalization with Chinese characteristics,” which has forged global interconnectivity through Chinese-funded infrastructure projects, such as those in the Belt and Road Initiative, alongside the establishment of new institutions that provide an alternative to trade and capital liberalization. With the US-China confrontation coming to a head, Mexico must now develop a trade strategy that recognizes its triangular relationships within a chaotic and moving geopolitical arrangement. The absence of a clear trade policy could harm companies specialized in foreign trade and undermine the basis of Mexico’s export-oriented economic model.

Development and trade in Mexico

In 1988, former President Salinas de Gotari implemented a rapid and far-reaching export-oriented industrialization strategy to control inflation, limit the fiscal deficit, and boost foreign trade. Across the domestic economy, however, export-oriented industrialization has had disappointing results—low GDP growth, stagnant investment rates relative to GDP, and reduced real minimum wages compared to the early 1980s. The Mexican export model was based around a small group of foreign and Mexican firms with minimal forward and backward linkages. Historical export incentives—such as exemption from tariffs, income tax and value added tax—became disincentives over time, as massive incentives were created to import parts and components. Unlike the experience of East Asian countries, export-oriented industrialization failed to incorporate exporting companies into the national productive apparatus, proving a lack of “territorial endogeneity.” Until recently, export processes in Mexico had specialized in low value-added processes and products, under the notion of “temporary imports for export.”)Global Manufacturing Export Value Added (VAEMG)(<)/a(>): a. accounts for 2.4 million jobs (or just 4 percent of the economically active population) and the CGVAA for 24.09 percent; the automotive segment barely accounts for 4.71 percent and the auto parts 19.39 percent in 2021, b. CGVAA’s VAEMG is higher than manufacturing, but particularly in its automotive segment, 39.76 percent in 2021 (and 33.48 percent in 2003); for its main supplier, the auto parts segment, the coefficient was just 17.14 percent in 2021 (and 10.26 percent in 2003).” class=”footnote” id=”footnote-6″ href=”#footnote-list-6″>6 The gap between productivity gains and real wages (the “Fordist equation”) widened, producing social tension and instability. Today, the Mexican economy faces multiple structural problems: low growth, limited fiscal capacity (specially in revenue generation), very low levels of investment in science and technology, a weak domestic supply structure for exports, and low real wages. These conditions stem from the country’s industrial organization, in which manufactured processes and products depend heavily on imported parts and components.

“Globalization with Chinese characteristics”—prevalent since 2013—has reformulated this economic model, heightening interconnectivity and infrastructure as the central axis of Mexico’s international cooperation strategy. This new globalization can be contrasted with the postwar Bretton Woods settlement, in which the global economy was based on the liberalization of capital, goods and services and benefits streamed to higher echelons of society. The Chinese proposal, unlike its Western counterpart, has sought to improve the quality of life of the global South, promoting infrastructure projects that benefit greater swaths of the population. This model draws from China’s own experience of recent decade and represents a direct and explicit alternative to the US-led global project, laying the foundations for the direct confrontation of these two visions.

US-China competition in the twenty-first century places third countries in a challenging position. Third countries don’t just face a trade war, as it is often simplified in public discourse, but a much deeper and structural dispute. For third countries in Latin America, doing without either China or the US is not a viable option at present. The concept of the new triangular relationship is also distinct from debates around a new Cold War. Aside from the Cold War era space race, the current systemic competition between the United States and China is incomparable. China’s science and technology budget is approaching 2.5 percent of its GDP—an absolute amount comparable to that of the United States.

The US Congress’s US-China Economic and Security Commission (2024) has highlighted concerns around China’s technological advances, particularly in advanced semiconductors, energy, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, quantum technology, biotechnology, and advanced batteries. China already has multiple advantages in several sectors, even before the DeepSeek breakthroughs were made public. Recent studies by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (2024) have noted that Chinese companies currently lead in fifty-seven out of sixty-four “core technologies” in 2020-2024, while from 2003–2007 US companies led in sixty out of sixty-four technologies, and China just three. These advancements in Chinese technology over a short period of time have been framed as a central concern of US national security, thus serving the justification for a new global trade strategy focused around “security-shoring.”

Security-shoring

In 2023, Janet Yellen, then Secretary of the Treasury stated categorically that US strategy towards China would prioritize national security, presenting a new paradigm of security-shoring. Issues such partner development, free trade, multilateralism and even reciprocity have since been subordinated to the goal of national security. The Biden administration framed its China strategy under the slogan “invest, align, compete,” through the notion of “managed competition.” Massive investments aimed at confronting China’s rise, accounting for 15 percent of US GDP in 2022, make up the core of this strategy.

Unlike Trump’s first government, which sought a bilateral solution between the United States and China, the current Trump administration has attempted to force third countries into this dynamic most aggressively through the imposition of tariffs, referencing national security in a slew of orders around the US relationship to Canada, Colombia, Panama, and Mexico. Competition is concentrated in technologically strategic sectors, with the goal of preserving US leadership in innovation. Until now, the United States has concentrated its security-shoring strategy on high-tech semiconductors, limiting Chinese FDI, exports, and FDI to China. In other sectors, including artificial intelligence, electric transportation and healthcare, the United States is not a technological leader.

Security-shoring is closely linked to new triangular relations for third countries. In the case of Mexico, security-shoring has transformed the economic terrain. The US has tried to pressure Mexico to restrict Chinese investments in Mexico and announced massive 25 percent tariffs on all Mexican imports except for products covered under the USMCA. But even the future of the USMCA, which Trump signed in 2020 remains an open question. Tariffs openly contradict the treaty, and its review is scheduled for 2026. Trump’s threats around the US trade difference, as well as the issues of fentanyl and water access, are likely to emerge in tense negotiations.

Mexico’s foreign trade with China and the US (2000–2024)

We can see Mexico’s new triangular relations through an examination of foreign trade. From 2010 to 2022, foreign trade in goods and services accounted for 72.42 percent of Mexico’s GDP. This is a significant jump from earlier periods, reflecting the depth of Mexico’s export-centric economy: from 1980 to 1988 foreign trade accounted for just 28.38 percent of GDP, and it accounted for under 10 percent until the early 1980s. Mexico’s export orientation and dependence on foreign trade is also significantly higher than the rest of LAC, where regionally, foreign trade accounted for 48.06 percent of GDP during the same period). Mexico’s foreign trade dependence is also higher than China (where foreign trade accounted for 41.46 percent of GDP), and the United States (where foreign trade accounted for 27.86 percent of percent).

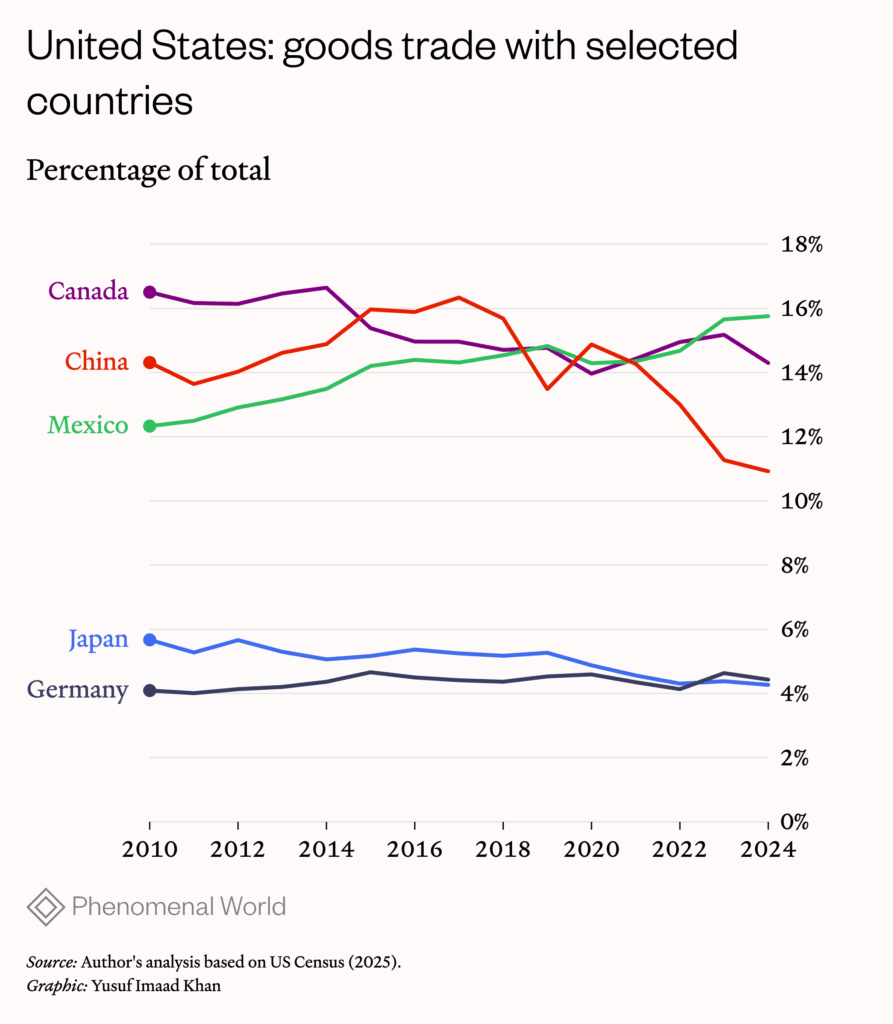

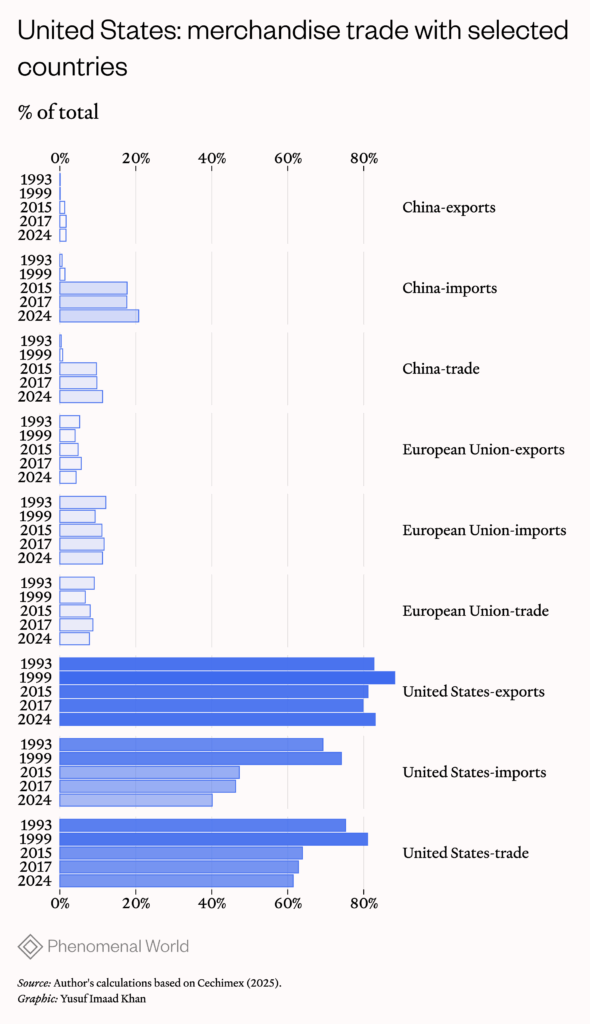

Foreign trade is clearly a fundamental aspect of the contemporary Mexican economy, which is now exposed to profound changes in the international order. As a result of a growing “trade war” and the attempted decoupling between the US and China, China’s share of US trade fell from its peak in 2017 (at 16.34 percent and the US’s top trading partner) to 10.92 percent in 2024, when China became the US’s third largest trading partner after Mexico and Canada. Imports from China fell from 21.59 percent of total US imports in 2017 to 13.43 percent in 2024. Accompanying this shift, Mexico became the top US trading partner in 2023, consolidating its presence in 2024 with respect to Canada and China (Figure 1). Mexican tariffs on total US imports have been increasing from 1.23 percent on the amount of imports in 2008 to 2.34 percent in 2024. In 2024 Mexico paid a tariff of 0.25 percent on its total exports to the United States; the tariff was 10.66 percent for China. Trump’s tariffs—a 25 percent tariff on steel, aluminum and autos—is 100 times higher than what Mexico paid for its exports to the US in 2024. The US threat has tried to prevent third countries like Mexico from becoming a “back door” for Chinese imports.

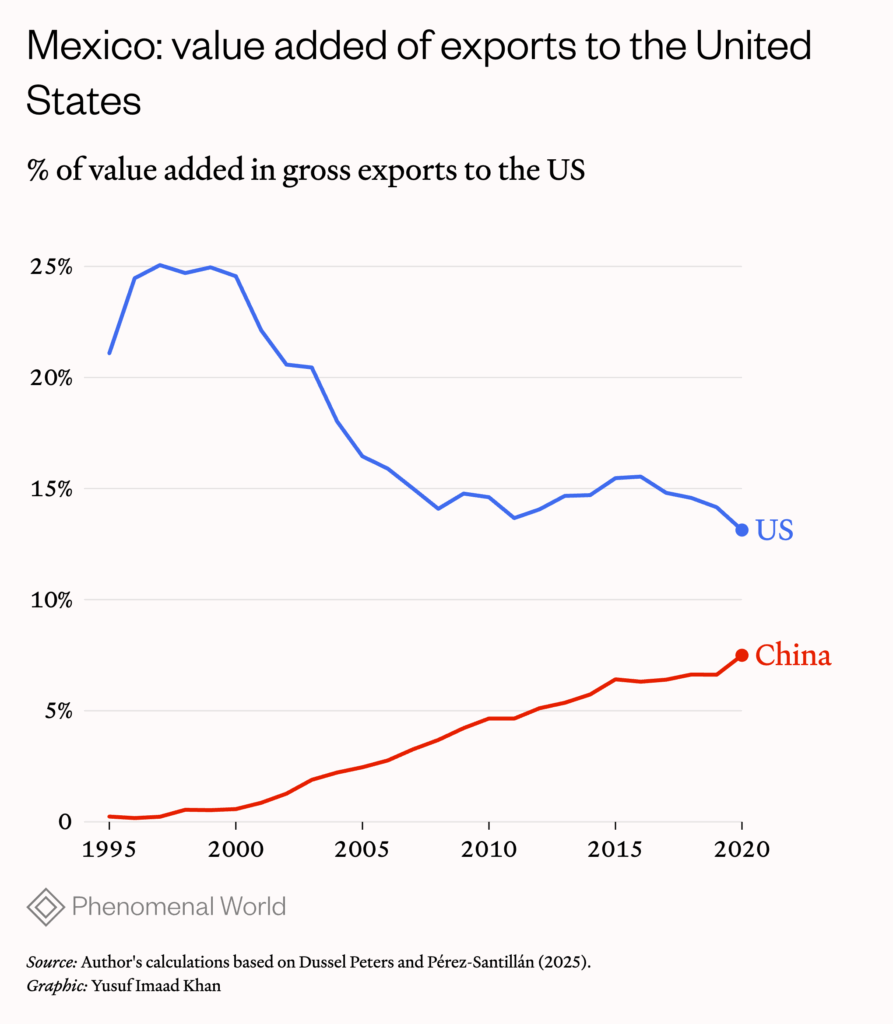

This rapid and profound process of trade disintegration between the world’s two major trading powers bears profound consequences at the firm, regional, and national level. Recent studies based on input-output matrices have shown that the domestic value added in LAC exports to the United States has been declining steadily since 1995, from 73.3 percent in 1995 to 68.77 percent in 2020. The differences between countries are notable: while Brazil reached 82.3 percent domestic value added in its exports to the United States in 2020, Mexico only added 64.3 percent domestic value added. On the other hand, Chinese value added in Mexican exports to the United States has increased steadily to reach 7.5 percent in 2020, though 70 percent of Mexico’s imports to the US are manufactured by US firms. China’s value added in Mexico’s exports to the US make up 21.2 percent of foreign value added, a higher percentage than in Costa Rica (10 percent), Brazil (13 percent), and Colombia (13.3 percent). The US is still the largest source of LAC’s foreign value added, but its share has fallen from 59.1 percent in 1995 to 35.8 percent in 2020.

Exports from LAC to the US: Percentage of domestic added value (1995–2020)

ArgentinaBrasilChileColombiaCosta Rica199589.887.984.788.579.1199689.68884.188.478.519978986.983.688.478.6199889.686.982.689.178.3199990.28583.39278.8200090.784.681.587.778.5200191.282.979.686.779200289.983.679.586.779.3200389.384.278.28779.1200487.18479.187.578.2200587.28577.388.476.920068785.57988.675.2200786.18678.588.676.1200885.385.475.588.276.1200987.48779.390.779.1201087.386.48091.379.6201186.985.677.790.979201287.184.878.591.179.320138783.778.391.280.6201488.784.379.888.181201588.8838287.383.2201687.284.383.686.883.6201787.184.483.287.582.3201886.582.481.687.181.1201986.582.181.786.782.2202088.482.382.288.181.8Source: Authors’ own elaboration (Dussel Peters and Pérez-Santillán 2025)

The complex structure of the external value added in Mexican exports to the United States has created a new industrial export organization from Mexico, oriented towards the United States and with a growing Chinese value added. Moreover, direct US imports from China have been increasingly substituted by imports from Mexico, which in turn incorporate Chinese inputs.

Even in the face of Chinese trade growth, the United States continues to be Mexico’s main trading partner. In 2024, 83.06 percent of Mexican exports went to the US, the highest share in the twenty-first century. At the same time, Mexico received an all-time high share of imports from China (20.76 percent). By 2024, these new triangular relations consolidated in the highest concentration in exports to the United States and imports from China.

Nonetheless, Mexico has a drastic trade deficit with China, its largest relative to any other country, with an import/export ratio of 13 to 1 in 2024. Mexico also has a significant surplus with the US, with an import/export ratio of 0.49 for the same year. A process characterized by massive imports of inputs from China, assembly in Mexico, and the subsequent export of final goods to the US explains these trade dynamics.

The table below presents the five main items imported by Mexico from China in 2024, which accounted for 75.05 percent of total imports from China that year. In addition to the interesting composition of Chinese imports–-significantly concentrated in electronics, auto parts and, increasingly, in the automotive sector—we can see competition between Chinese and US imports to Mexico. Across these three sectors, imports from the US were by far the most relevant historically in Mexico. In 1995, for example, Mexican imports in electronics and auto parts from the United States represented 79.2 percent and 35.5 percent of total Mexican imports in these areas. Chinese participation, alongside imports from the European Union and Asia, was secondary. We now see a drastic shift in the present. In 2024, for example, Chinese imports accounted for 33.6 percent of Mexico’s total electronic imports in 2024. These imports have been growing significantly since the beginning of the twenty-first century and have displaced U.S. imports since 2006 (which accounted for only 21.7 percent).

Similar competition trends can also be seen in auto parts. In 2024, for the first time, Mexican imports from China in this sector were higher than those from the United States. Throughout the automotive supply chain, transnational companies source parts and components from their own plants or from third-party companies established in different countries, at times making it difficult to establish trade relations.

Mexico: imports from the US and China (1995–2024)

Imports from China

19952000201020172018Electronics0.811.9630.1735.5035.82Auto parts0.381.6423.6822.6924.11Automotive0.060.233.337.408.99Special classifications0.170.0016.5020.7619.19Plastics0.540.975.899.059.03Total0.721.5415.1317.6417.99Based on major imports from China in 2025, percentage of total imports in each sector. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on data from Cechimex (2025)

Imports from the US

19952000201020172018Electronics79.201.9626.7424.7723.39Auto parts61.6376.5540.1438.4637.27Automotive80.0972.1858.8748.3748.62Special classifications67.760.0026.8735.0636.57Plastics89.7089.1474.6866.8465.51Total74.4970.3248.2546.3846.58Based on major imports from the US in 2025, percentage of total imports in each sector. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on data from Cechimex (2025)

Towards a non-exclusive triangulation

Over the course of the year, US trade negotiations with all trading partners will impart enormous economic repercussions for Mexico. The processes of temporary imports for export in Mexico will undergo important changes, though at the moment it’s unclear if these impacts will be positive or negative for the country in the short and medium term. The specific conditions of this new triangular relationship will vary depending on the third country, across issues of investment, infrastructure, tourism, and services. Certainly this new triangular relationship will result in diverse configurations, in which the US and China alternate in significance. For Mexico, the US-China tariff war has disrupted decades-long processes of commercial specialization, generating profound uncertainty for thousands of foreign and Mexican companies embedded in the country’s model of industrial organization. This new triangular relationship is not the result of security-shoring—the growing presence of China in Mexico’s foreign trade can be traced back to the beginning of this century, with foreign companies established in Mexico, and particularly U.S. companies, as the main actors importing from China.

Nonetheless, security-shoring since the Biden administration—and intensified under Trump—has reshaped the terrain. The accusation that Mexico is a “back door” for Chinese value added misunderstands the country’s industrial organization. Transnational companies established in Mexico that import massive quantities of parts and components for their exports to the United States. Surely some of these processes could be reversed, although these intra- and inter-firm links took decades to develop.

There are a few proposals attempting to address this new triangular relationship. One proposal is the creation of a strategic agenda formed between the Senate of the Republic, universities, and relevant ministries, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit, and the Ministry of Economy. This agenda would seek to promote economic diversification and formulate a coherent and proactive policy to navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by China’s rise. A Subcommittee on Mexico and China within the Senate could also coordinate economic, trade and infrastructure issues. Finally, a new stage in the bilateral trade relationship with China could refocus on issues of technology transfer and Mexico’s place in higher value segments of the global value chain, while promoting Chinese FDI in strategic sectors. For now, the Mexican state and the private sector have focused their actions on responding to the US, but they must also define a strategic agenda with China. The failure to do so will bring enormous costs for Mexico, undermining an economic model grounded by foreign trade.