One of the most important chapters in the history of the anthracite coal industry concluded 123 years ago this month.

The Great Strike of 1902, a landmark in the annals of labor-management relations, ended when an estimated 140,000 miners returned to work on Oct. 23, 1902.

It was, as the headline in the Pottsville Republican put it, “The Day of Resumption of Work at the Mines.”

“At 6 o’clock this morning, a chorus of whistles for the first time in five months greeted the gray dawn at collieries throughout the Schuylkill region, and shortly afterward thousands of men and boys were on their way to work, and the long strike was definitely at an end,” the paper reported. “At all of the collieries in the immediate vicinity, work was resumed on a small scale this morning.”

Having been idle for so long, it took until noon until coal of any significant volume made its way through the breakers.

Though it marked a turning point between mine owners and the fledgling United Mine Workers, the strike was important for another reason — it took the intervention of the president of the United States to settle it.

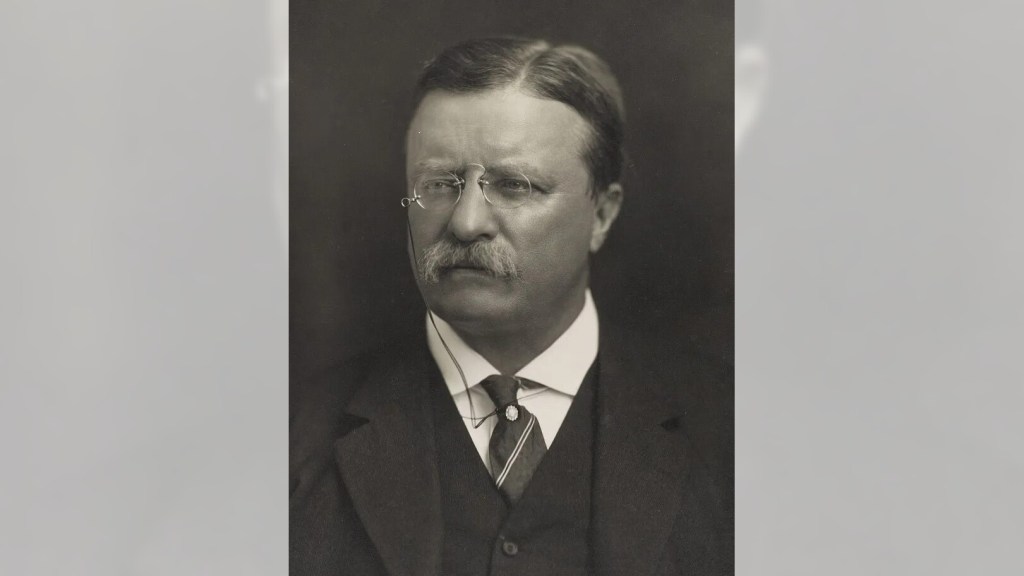

With winter approaching and East Coast families dependent on anthracite for home heating, President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt feared there could be what historians have termed a coal famine. A shortage of heating fuel, he feared, could result in riots.

Roosevelt formed the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission in an attempt to arbitrate the dispute.

Presidents had intervened in strikes before, but always on the side of management. Roosevelt’s initiative was the first time the federal government intervened as a neutral party, and it set a policy precedent for the government’s response to future disputes..

On Oct. 3, 1902, Roosevelt summoned both parties to the temporary White House — the real one was undergoing renovation — and appealed for an end to the strike for the greater good of the country. He asked for an immediate resumption of work in the mines to meet “the crying needs of the people.”

If his Mister Nice Guy approach failed, Roosevelt, master of the “speak softly and carry a big stick” foreign policy, was prepared to nationalize the mines.

Though there was unease on both sides, the strike ended 20 days later.

The UMW’s 32-year-old president, Johnny Mitchell, won union members a 10% wage increase and a 9-hour day (it had been 10). The mine owners, however, did not have to recognize the union as sole bargaining agent for miners.

The resolution of the strike, settled through negotiation, was in contrast with the state of affairs only 25 years earlier when the so-called Molly Maguires were hanged in Schuylkill and Carbon counties. And, just five years earlier, 19 immigrant miners marching peacefully in support of a strike were gunned down by sheriff’s deputies in the Lattimer Massacre.

Still, there was fear of clashes between union and non-union miners, who had continued to work during the strike. Pennsylvania National Guard troops had been dispatched to the region to quell violence should it erupt.

At Wadesville, Silver Creek, Good Spring and Brookside, where non-union workers kept the mines open during the strike, the situation was “a delicate one” as UMW miners returned to work, the Republican reported.

In Treverton, a hotel owner fired a shot into a crowd that threatened a non-union worker living in the hotel.

More telling, though, was a short story right next to the back to work report in the Pottsville Republican.

Reopening a shaft, it said, two miners were burned when a gas explosion hurled them 20 feet in the air.

Originally Published: October 11, 2025 at 7:35 PM EDT