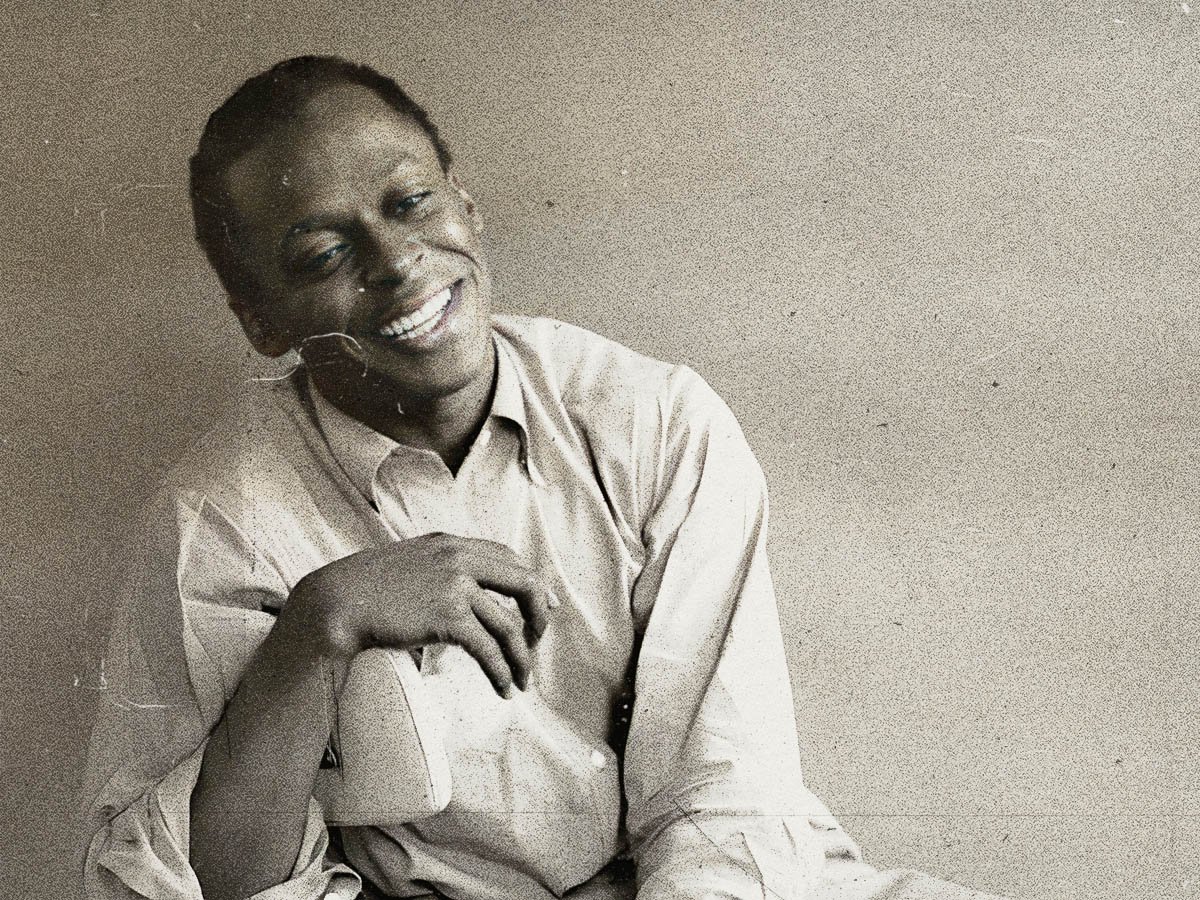

(Credits: Far Out / Tom Palumbo)

Sun 12 October 2025 0:30, UK

Interpolation, cultural appropriation, and crossing into territories you shouldn’t are three of the biggest issues across today’s music industry. Miles Davis once had a major issue with the latter.

When we look back at some of the most major moments in music history, it’s hard not to grimace at how distasteful it was. Cher still gets a hefty amount of heat for her controversial ‘Half-Breed’ for all the same reasons some people feel uncomfortable watching Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ music video. Across rock, blues, and other major genres in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, there was also the emergence of the ‘cover’ song, which countless artists have looked back on less fondly than how we regard them today.

Put simply, historians, musicians and everything in between have seen the emergence of the cover as something that quite literally covered markets the original couldn’t. Don McLean once said, “If a Black act had a hot record, the white kids would find out and want to hear it on ‘their’ radio station,” a sentiment echoed by DJ Luxxury, who said, “The origin of the term ‘cover version’ is you’re covering a part of the market not covered by the original. If this audience is hearing it, this audience isn’t. This goes back to the racist origins of cover versions, but to oversimplify it, the rock ‘n’ roll record gets it to the white people.”

Finding issues with how artists found ways to sidestep the industry’s inherent racism problem isn’t a new thing. Neither is looking at all the ways that white acts and bands ‘borrowed’ elements from predominantly Black genres like rhythm and blues to further their development and popularity. The Rolling Stones is a prime example, Keith Richards taking his love for people like Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters and BB King and injecting it into the Stones’ distinctive flavour of rock ‘n’ roll.

Eric Clapton did the exact same thing. The list is endless – people took the things they loved and made them their own. Which in itself isn’t bad, but becomes a bit trickier to decipher when you think about how the more privileged people profited from minor communities just because it was the way the system worked. It’s like all the reasons Miles Davis once went after Blood, Sweat & Tears. Not only did they try to be something they weren’t, they also did it in a way that he found “embarrassing”.

When you dissect his words, which came during a 1969 interview with Rolling Stone, he was seemingly embittered by a few things, like how they also assumed the role of revolutionaries when what they’d done was already dated. “It’s social music. There’s two kinds – white and black, and those bourgeois spades are trying to sing white and the whites are trying to sound colored. It’s embarrassing,” Davis said.

He went on: “Blood, Sweat & Tears is embarrassing to me. They try to be so hip, they’re not. They try to sing Black and talk white. I know what they do: they try to get Basie’s sound with knowledge, put some harmonies in it – instead of a straight sixth chord, they’d use a –shit, I can’t call chords anymore — a raised fourth or some shit like that, with the tonic on top. It was done years ago.”

He also praised James Brown and “those little bands on the South Side”, saying he appreciated them because “they swing their asses off” and there’s “no bullshit”. All the other “white groups”, he added, didn’t quite cut it because they had to rely on “hair and funny clothes” to “get it across”.

To create good music, therefore, Davis claimed there needs to be a range of talents. Jimi Hendrix, in his view, gave as good as he got because he could “take two white guys and make them play their asses off”. It has to feel authentic, and where people often went wrong was the lack of know-how because it wasn’t their thing to begin with. Which, as we all know, paves the way for some of the most inauthentic-sounding groups of all time.

Related Topics