The world’s finance ministers and central bankers gather in the US capital this week with a burning question preoccupying their minds: what exactly is the true state of the world’s largest economy right now?

The great and good of economic policymaking, including Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, and Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, are in Washington DC for the annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

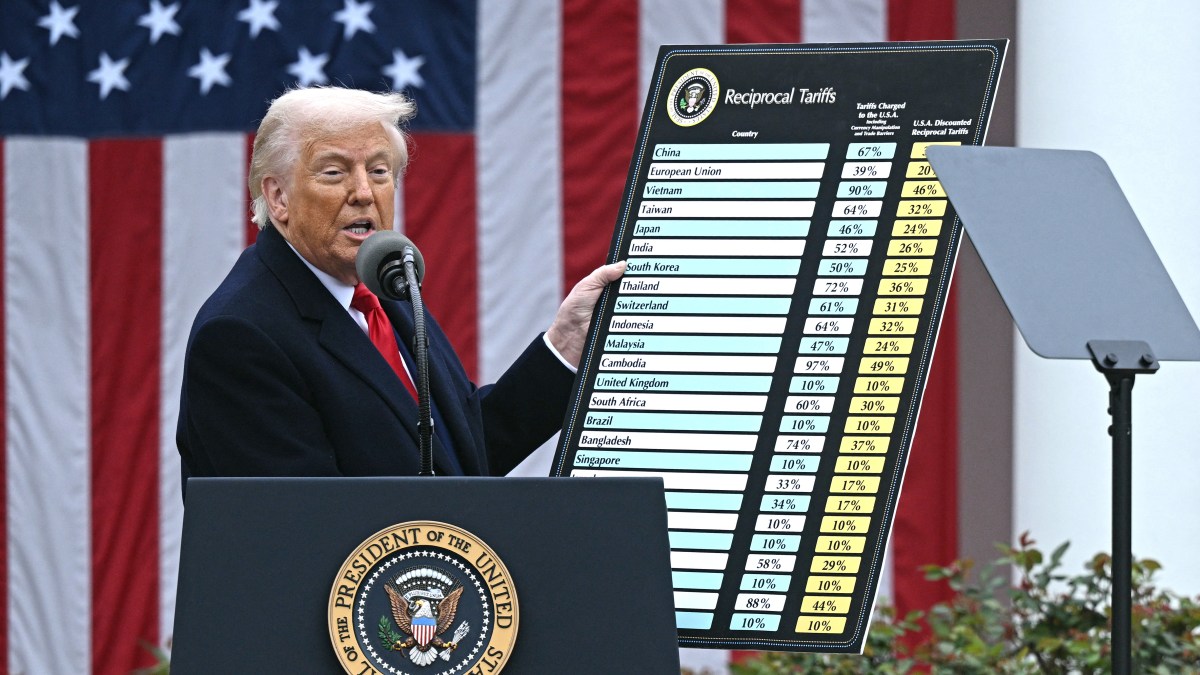

At the IMF’s last gathering in April, markets had just been jolted by the shock of President Trump’s “liberation day” tariffs blitz that caused a sharp slide in the dollar, rising US government borrowing costs and warnings about fragile financial stability and a looming recession.

Today the US stock market is continually hitting new records, the AI investment boom is powering domestic growth and the dreaded tariff-induced recession has not materialised in the form of spiralling inflation or a shrinking jobs market. The US economy grew at an annualised rate of 3.8 per cent in the three months to June, by far the strongest performance in the G7.

Scott Bessent, Trump’s most senior economic official and the treasury secretary, is expected to use the meetings as a victory lap for government policies and another case of how the mainstream economics profession has consistently made false predictions about the impact of tariffs, migrant deportations or its fiscal spending. In April Bessent delivered a blistering speech accusing the IMF of having a “Pollyannaish outlook symptomatic of an institution more dedicated to preserving the status quo than asking the hard questions”.

Scott Bessent in Washington last week

ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo, said this month that the performance of the US economy should force “the economics profession … to look ourselves in the mirror”.

He added: “The forecast for the past nine months has been that the US economy would slow down but the reality is that it has simply not happened. The bottom line is that the US economy remains remarkably resilient and it is becoming increasingly difficult to argue that we are still waiting for the delayed negative effects of what happened six months ago on liberation day in April.”

The IMF meetings come at a sensitive moment for the fund, which is under pressure from the White House, its largest shareholder, to reform. Trump and Bessent have said they will not quit the Bretton Woods institutions but want them to ditch climate change or gender equality goals through their lending and instead home in on policing China’s un-balanced trade surplus. The IMF has also been bounced into providing tens of billions of dollars in aid to Argentina, whose president Javier Milei is Trump’s closest ally and ideological bedfellow.

President Milei

LUIS ROBAYO/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

• Argentina’s Milei shows how far Trump will go to back his friends

In her curtain-raiser speech before the meetings last week, Kristalina Georgieva, IMF managing director, was at pains to emphasise that the fund was not among the naysayers predicting a US recession and that the world’s largest economy had “held up” despite the tariffs. Georgieva has been careful to avoid explicit criticism of trade protectionism, highlighting instead that effective US tariff rates are not as prohibitive as first feared in April.

Gita Gopinath, Georgieva’s former deputy and ex-IMF chief economist, who left the IMF earlier this year, is now less diplomatic. She says the score card for Trump’s trade policies is “negative” as the levies are “a tax on US firms and consumers” and have yet had no impact on shrinking the country’s trade deficit or creating any manufacturing jobs.

Kristalina Georgieva last week

JONATHAN ERNST/REUTERS

Most economists still expect tariffs to raise goods price inflation, for migration restrictions to seriously impinge on the supply of workers and tax cuts to create loose fiscal policy that will not be counteracted with tighter monetary policy as the central bank cuts interest rates.

Tariffs have begun to show up in some parts of goods inflation but the full impact has been delayed by US companies stockpiling imports at the start of the year before tariffs. So far importers have also absorbed most of the rise in costs from tariffs in their margins, rather than pass them down to consumers. This is unsustainable and will eventually result in consumer price inflation hitting 3.5 per cent next year and staying above 3 per cent for most of the year, according to figures from the Peterson Institute.

One of the biggest factors helping the US economy to outperform this year is the mammoth rates of investment from tech firms in building up AI capacity, in the form of data centres and software. Without capital spending in these two areas the US economy would be close to a recession this year, according to the likes of Jason Furman, chief economic adviser to President Obama, and a point highlighted by researchers at Deutsche Bank.

“It may not be an exaggeration to write that Nvidia, the key supplier of capital goods for the AI investment cycle, is currently carrying the weight of US economic growth,” George Saravelos, at Deutsche Bank, said. “The bad news is that in order for the tech cycle to continue contributing to GDP growth, capital investment needs to remain parabolic. This is highly unlikely.”

The AI spending boom is powering the US stock market to new highs, with all the gains concentrated on “hyperscaler” tech firms such as Nvidia, Microsoft and Google. The country’s five biggest tech firms have equity valuations larger than all the stocks listed on the Eurostoxx 50, the UK, India, Japan and Canada, according to Goldman Sachs. “Many investors have started to ask whether all of this is rational or if we are seeing the classic signs of an unsustainable bubble,” the bank said.

Dario Perkins, director of global macroeconomics at TS Lombard, thinks the “recession-without-AI” narrative ignores the degree to which other parts of the economy are offsetting the drag caused by AI firms importing their chips. Recessions are also not only growth slowdowns but require substantial falls in employment, he said.

“The economy is more likely to reaccelerate than stall. Policy, both fiscal and monetary, is turning more expansionary and an improvement in sentiment should unlock pent-up demand. With supply impaired, inflation is likely to make a comeback, too” Perkins said.

Views on the true state of the economy have been clouded by a pause in official data releases since the federal government shutdown began on October 1. Closely watched monthly payrolls figures were not published as planned this month and the shutdown could extend into next month, delaying publication of key inflation numbers for September.

For the pessimists, there are already worrying signs of fragility in the private sector. First Brands, a Texas-based autoparts maker, declared bankruptcy last month and its heavy reliance on private credit is steadily rippling through Wall Street, shining a spotlight on high-profile names such as Millennium, UBS and Jefferies.

The IMF/World Bank meetings are unlikely to provide visiting dignitaries with much clarity on whether the US is booming or on the precipice of a significant slowdown. Its trajectory will, however, be the most significant factor shaping economic outcomes on the rest of the world for the foreseeable months.

“The US economy … is the source of the greatest uncertainty and volatility, probably the biggest change agent in the world,” Adam Posen, director of the Peterson Institute, said. “So what happens in the US in terms of growth, inflation, policy response is probably the biggest driver [for the world economy].”

Meanwhile in France …

The French political crisis risks lurching it into years of stagnation unless its leaders confront the country’s structural economic problems: an ageing population, rising government debt and urgent need for more investment, analysts have warned (Jack Barnett writes).

The country’s parliament has been stuck in deadlock since legislative elections last year that handed sizeable wins for the Socialist Party and the far-right National Rally, formerly led by Marine Le Pen.

A procession of prime ministers appointed by President Macron have resigned after they failed to get either Socialists or National Rally politicians to back plans, including raising the retirement age and scrapping some bank holidays, to rein in the deficit.

• Macron’s malaise isn’t just bad for France, it’s infecting Europe too

The deficit is projected to persist at more than 5 per cent of GDP for the next few years without proper fiscal consolidation. Its debt-to-GDP ratio is already 114 per cent, the third highest among the 20 members of the Eurozone.

Carsten Brzeski, global head of macro at the Dutch bank ING, said in a note to clients: “The number of prime ministers isn’t the cause of instability, it’s a symptom. It suggests that something in the economy and/or society is in need of repair.

“In France’s case it’s the unresolved dilemma of how to reconcile rising government debt and ageing populations with the urgent need for investment and structural reform.”

President Macron recently named Sebastien Lecornu as his new prime minister, France’s fifth since the start of last year. Lecornu was in a race against time on Sunday to form a government by Monday’s budget deadline, as divisions emerged within the conservative Les Républicains party over whether to accept ministerial posts in his cabinet.

Sebastien Lecornu

MARTIN LELIEVRE/POOL/REUTERS

Also key to Lecornu’s success in getting a handle on France’s deficit is making sure that the Socialists are on side, probably meaning that he will have to offer a totemic progressive tax measure, such as the reintroduction of a wealth tax.

• Ex-PMs urge Macron to resign as allies desert French president

Gabriel Zucman, an influential French economist at the Paris School of Economics, has proposed a levy of least 2 per cent on estates bigger than €100 million. Olivier Blanchard, the former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, has supported such plans.

Analysts at Berenberg Bank said that the new government “will probably not resolve France’s underlying problems. To entice the Socialists to join a coalition the centrists will likely have to give them something and the main things the Socialists want at the moment are a wealth tax, a suspension of the pension reform and less fiscal consolidation overall. These policies would put further pressure on the French fiscal path.”

There had been speculation that Macron would call an early presidential election to break the parliamentary impasse but the appointment of another prime minister would make this unlikely.

Investors are worried about the sustainability of the public finances. The difference between the yield on the French benchmark ten-year government bond and Germany’s, known as the “spread”, is about 0.8 percentage points, the highest since the Eurozone debt crisis.

Elsewhere, the yield on Japanese long-term government debt rose sharply last week after Sanae Takaichi won the leadership election of the ruling Liberal Democrat party, raising expectations of a sharp increase in public spending.