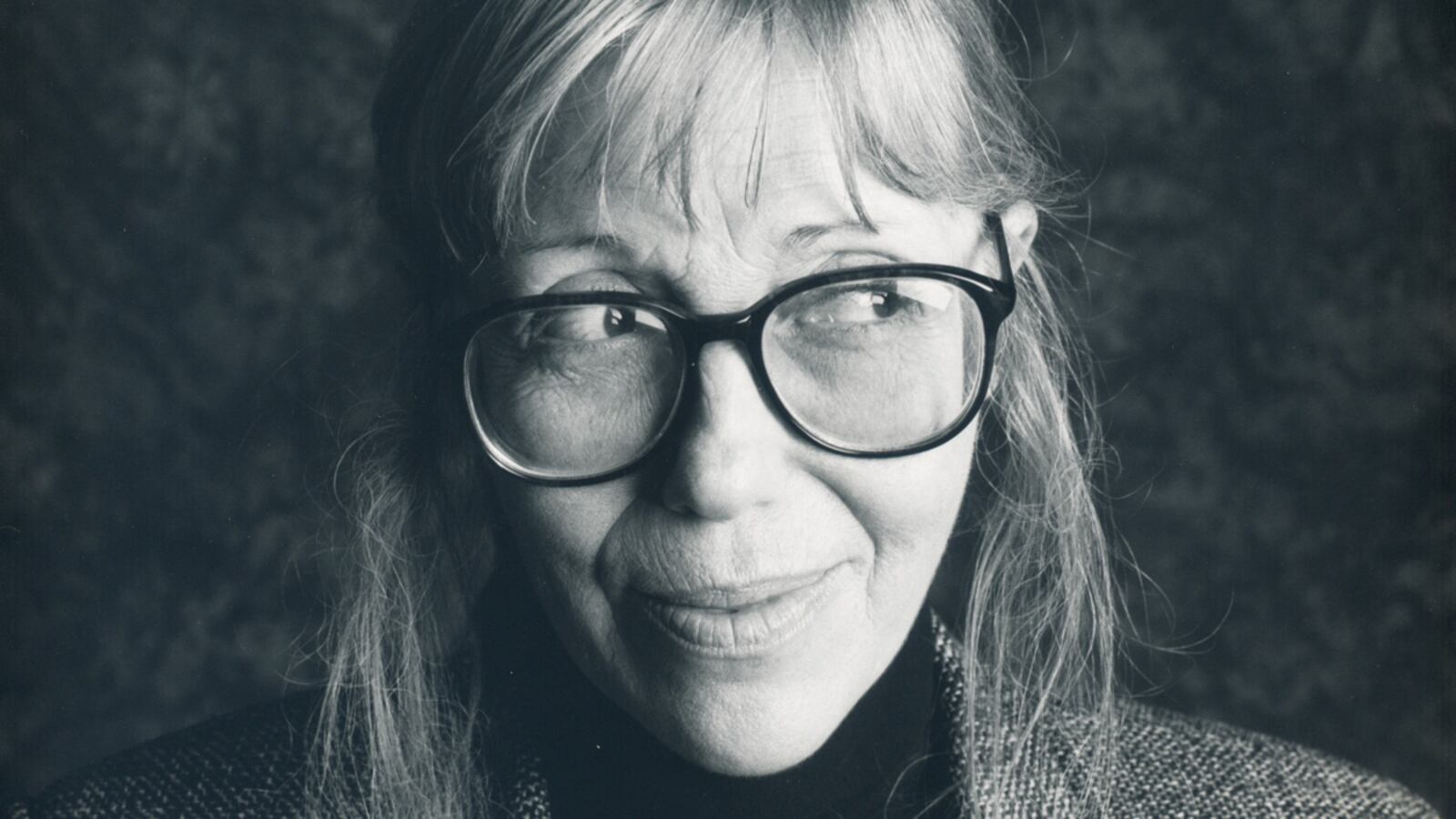

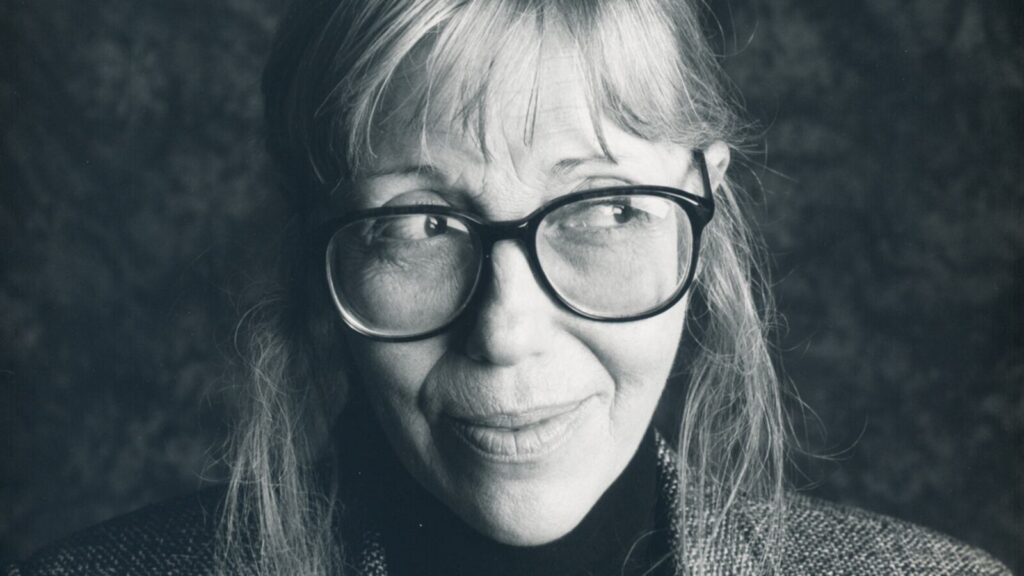

Katherine Dunn (1945-2016) is best known for her National Book Award-nominated novel, “Geek Love.” A collection of her short stories, “Near Flesh,” was released last week by Macmillan Publishers. Photo courtesy: Katherine Dunn estate

Katherine Dunn (1945-2016) is best known for her National Book Award-nominated novel, “Geek Love.” A collection of her short stories, “Near Flesh,” was released last week by Macmillan Publishers. Photo courtesy: Katherine Dunn estate

I have a confession to make: I have never read Geek Love.

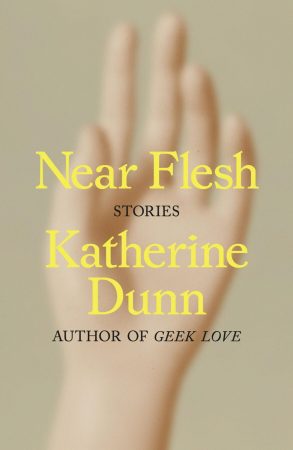

The late Katherine Dunn’s acclaimed novel, about an itinerant family-circus freakshow, has been enthusiastically recommended to me by numerous bookish friends. I even own a copy, which, as of this writing, occupies a spot on my shelf alongside dozens of other smooth-spined paperbacks, a row of guilty reminders that buying books and reading books are indeed separate hobbies. Knowing Dunn’s work only by reputation, I felt uniquely unqualified to review Near Flesh, her second posthumous release (her novel Toad was published in 2022) and first published collection of short fiction.

My saving grace was the strength of Dunn’s sinewy, unforgiving prose — the distinctive lexical connective tissue binding Near Flesh together. The 18 entries in this uneasy collection, released last week, explore the terrains of motherhood, the body, the natural world, violence, death, all with a steady infusion of morbid humor, and in language so evocative and idiosyncratic that, long before the last page, I felt sure that Dunn’s authorial voice had fingerprinted itself onto my consciousness, its loops and whorls so crisp, so specific that I could pick it out of an anonymous lineup of prose styles.

The book opens with Pieces, a web of vignettes concerning the fate of amputated body parts, some surgically removed, others lost by accident or acts of violence. In the world of this story, one cannot enter heaven with a body less than fully intact, and the careful provisions that must be made for lost limbs and excised organs animate the business operations and spiritual rites of an entire small town. Particular attention is paid to a finger, intentionally severed by a veteran in recompense for an act of mutilation against an enemy combatant during wartime. “It was discovered by a woman who massaged her moods with walks on the wooded park trail,” writes Dunn. “Her dachshunds, a mother-daughter pair, were fighting over it in the brush.”

The relationships between women and the wilderness, between mothers and daughters, are recurring sites of fear and turmoil in Near Flesh, as is motherhood itself. In The Allies, Mrs. Reddle swivels between contentedly painting in a corner of her kitchen to screaming invective at her family, landing blows on whoever is within arm’s reach. Her daughter Edie is an astute monitor of her mother’s moods, responding with cheerful misdirection and gentle mollification to any subtle shift that suggests an explosion is imminent, dutifully fitting herself to her mother’s rose-colored vision of her — a demand that takes on an increasingly bizarre shape as the story nears its conclusion.

In The Well, a young mother new to country living must brainstorm her own rescue, feeding instructions to her 4-year-old on how to help her hoist herself out of a well on their secluded property. Even while treading water and fighting the onset of fatigue, she thinks only of her child, and of the many perils that might befall her as she ventures home alone to retrieve a rope. The metaphoric imagery — the isolation, the impossibility of respite, the self-abnegation — is no less potent for being somewhat obvious.

In a similar thematic vein is The Education of Mrs. R, a wry degloving of rural domestic life that accompanies its title character engaged in the bloody business of slaughtering 49 roosters. Dunn spares no sensory detail: jerking legs, tumbling heads, the spray of blood on the hatchet blade — all are on grisly display. As she works her way through the bachelor flock, Mrs. R becomes increasingly feral. Her family recoils from the spectacle, her daughter fleeing in terror of the blood stains and clinging feathers, and when her disbelieving husband (who, it must be noted, ordered her to dispose of the nuisance birds) asks why she didn’t simply call the local meatpackers for help, Mrs. R points out that they would only wrap and freeze the birds, not kill them. “Did you ever think of that?” she wonders. “I did.” No one is equipped for this bestial version of her, nor for the naked reality of her domestic labor made visible.

Sponsor

I Had the Baby on My Left Hip — the shortest entry in the collection — is a page-long nightmare, describing the moments immediately before and after a deadly explosion with all the economy of Amy Hempel. Its narrator lays down the aftermath of the disaster in dislocated, impressionistic strokes, gesturing toward the unspeakable without naming it in so many words. The fragmented, bloody picture that emerges is made all the more horrifying by what is never said.

Near Flesh won’t be a universal crowd-pleaser. If you prefer to stay on the sunlit side of human nature, most of these stories probably aren’t for you. But if you get a thrill out of probing our shadowy corners; if you lean toward the grim, the gritty, the macabre; if you’re as likely to laugh as cover your eyes during a horror movie, then this collection will deliver — and it might even inspire you to pick up Geek Love.

***

More on Katherine Dunn in Oregon ArtsWatch: