NINA MOINI: In a new memoir, Janus Fairbanks writes, “Making the time to pass along a lesson is imperative to the survival of not only the humanity of Indigenous people, but of all people.” And she credits the women in her family for sharing lessons with her.

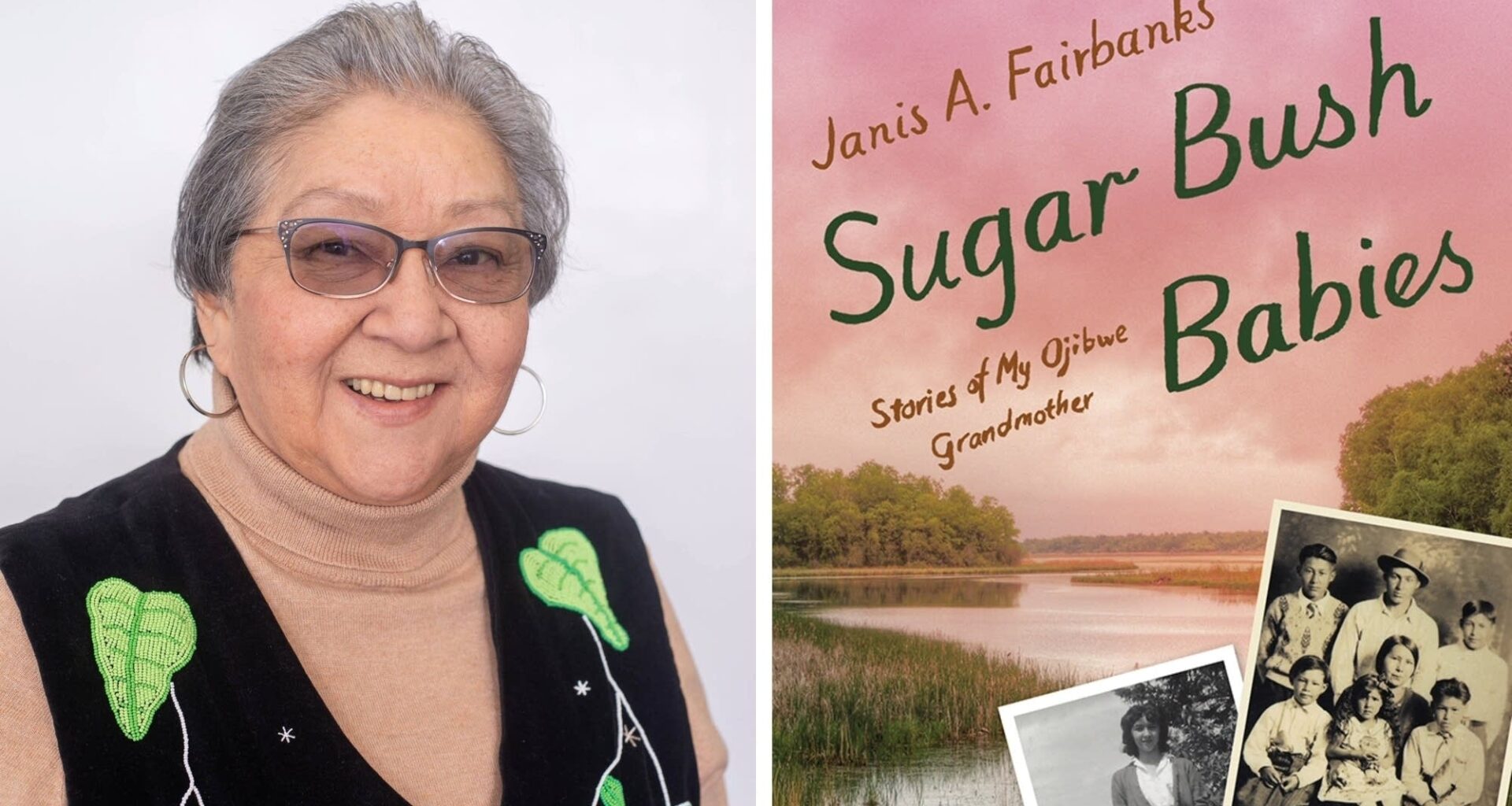

Fairbanks is a member of the Fond Du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and author of Sugar Bush Babies, Stories of My Ojibwe Grandmother. The stories are split, just like her childhood, between the city of Duluth and the lakes and woods of Northern Minnesota. She joins me on the line now. Janis, thank you very much for joining the program, and congratulations on the new book.

JANUS FAIRBANKS: Thank you very much. It’s nice to be here.

NINA MOINI: I love the quote that we started with, I don’t know if you heard that. Just the humanity and the lessons and that oral history that has existed for so long now, but now you also have a book and a written history, which helps from generation to generation to sustain traditions. And this book is dedicated to your grandmother. Do you want to tell us just a little bit about her?

JANUS FAIRBANKS: Well, my grandmother was the one, I think, that I spent the most time with when I was a child, other than being in school where I had to be. I was out at the lake with her. And the book is all– it’s only about my school years, from birth to about age 18, I think, when I graduated and left town.

But all the time in between that I wasn’t in school, I was with her, and I was usually the only one with her, although she had a lot of grandchildren. Sometimes my cousins or my sisters would come out there.

My brothers, I remember them being there one time because of a little incident that happened. They like to play bow and arrow with the little rubber-tipped arrows, and they were shooting it– they were safe about it, but they were little guys, about eight years old. And she came around the corner, and they had just released, and it stuck right in the middle of her forehead. And she didn’t– she just looked really surprised. “Hey! You kids! You shot me!”

NINA MOINI: Oh, no!

JANUS FAIRBANKS: It was just funny. I mean, it didn’t hurt her. They were just little guy– they were, I don’t know, they were six or seven years old, probably.

NINA MOINI: Yeah.

JANUS FAIRBANKS: Playing with those little wooden ones. But she– that’s how she was. Something happened, and she would just take it in stride, and make a little lesson out of it, of course. They had to go and aim in a different direction, they couldn’t be anywhere by the house after that.

NINA MOINI: Exactly.

JANUS FAIRBANKS: Yeah. That’s how she handled things. And it was never a big lecture or anything. She just got things done, and she had a reputation on the reservation, too, for– she was such a kind woman, and everybody has really nice things to say about her.

She was the first Councilwoman on the Reservation Business Committee, and I remember going to meetings with her, and before she would go, she was always just get things ready, this is important, this is business, and talking to me about, well, we have to take care of things, and make sure that everybody is OK. That was her big thing, taking care of the community.

And just watching her in action, I think that instilled that in me because I’ve always been a– put myself in a situation where I wanted to be someplace where I could do something good for our people. And so I worked with different community centers and made social gatherings.

And right now, I’m working with the Language Advisory Committee on my second term as the Chair of that committee, but before that, I was the Coordinator of the Language Program because I want people to learn our language and I want them to learn our culture.

So I think this book is going to help them see a little insight into why I am the way I am, for one thing, because it’s all the stories of me not just with grandma, but when I was in school, too. And all those lessons carried over to my interactions with my classmates, which started out kind of rocky because of it being the 1950s and them being used to cowboys and Indians warfare scenario.

Well, I wouldn’t go to war with them. I started telling them stories and entertaining them. So that worked much better. They liked my stories and asked for them.

NINA MOINI: So you were between two worlds for a long time, and it kind of informed– I’m sure a lot of people can relate to that experience, and I understand you mentioned all the work you’re doing on language preservation and growth and your mentorship now of writers, younger writers, writers of all ages, I’m assuming.

What do you tell them? What do you– yeah, what do you tell them about– what do you tell them about how to incorporate their own experiences into their writing, even if it’s not a memoir? Is that something that has to really be intentionally done?

JANUS FAIRBANKS: I think they do it anyway. I mean, I don’t have to tell them that. From the reading, the one writer’s group I belong to, there’s a very interesting man there. He was career military, and his stories all have to do with military. So they put themselves in it. And he’s a very good writer, too– I wish he would do something about getting published, but I’ll talk to him about that yet.

But for writers of all ages, it’s inside of them, and it will come out. Whoever or whatever their influences are or their life experiences, it’s going to come out in their writing anyway so I don’t have to tell them about that.

NINA MOINI: Mm-hmm. So there’s the work that you’re sharing with everybody, but also this deeply personal work. I want to go back to your grandmother for a moment because she had gone to a boarding school, I understand, which were created to break Native children’s connections to their culture. But she was a fluent Ojibwe speaker. She knew a lot about her culture. How was she able to hold on to those ties? And what do you take from that today with you?

JANUS FAIRBANKS: Well, when she was there, they separated them into a girl’s building, and she said there were little girls and little boys, and then she was with her age group. And the girls developed a sign language. And when they could, they still spoke their language.

And so that’s how she maintained hers. And she was always using it. Anybody would come over to the house, I remember them– I was just a kid, so I got out of their way so they could visit. But I was listening to them, and I could hear, and I could learn. If I heard words that I didn’t know, I would ask her about it after they left, after the company left.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. And look at you now, right? You have a doctorate in Ojibwe language, literature, and history, continuing on the tradition. I wonder what you want people, Janis, to take away from this, from reading this personal story.

JANUS FAIRBANKS: Well, I want them to understand that just because people are different than them in some way, that we’re really all the same. We all have the same values. We all– well, I shouldn’t generalize like that, but most of the people I’ve met, they love their family. They have a common respect for each other. Some of that, it’s getting affected by I don’t know what, I can’t analyze that, but some of them are not tying to each other.

And I don’t know, I think maybe too close a quarters and too few resources and all the social things that go on that affect people, and they’re not getting enough support, that’s what I put it to. And whatever shortfall they have, that’s not their shortfall, that’s a shortfall of society because that should be taken care of.

I remember writing a story about a fish in a– well, it was an assignment. It said, well, why is it important to feed these fish in this fishbowl, and what happens if you don’t feed them? And I thought that was kind of a silly assignment, but it was right up my alley. I know what happens to fish when you don’t feed them, they die. You can’t just neglect them there– you put them in a bowl because they’re beautiful. That’s not supposed to be about you, that’s supposed to be about the fish.

NINA MOINI: Yeah.

JANUS FAIRBANKS: Taking care of the fish. So that’s my outlook on things. I look at people, and if they’re– even if they’re not kind to me, I just look at, well, they don’t know me. How would they feel any kindness toward me if they don’t know me? So then I am very social. I like to talk to people. And then once they get to me, well, we get along fine.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. I love your message about just connection and about sharing your story. And I thank you so much for stopping by Minnesota Now today, we really appreciate your time, Janis.

JANUS FAIRBANKS: Well, thank you for having me.

NINA MOINI: Thank you.

JANUS FAIRBANKS: You have a nice day. You, too. Janis Fairbanks is a member of the Fond Du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, and the author of Sugar Bush Babies, Stories of My ojibwe Grandmother. It’s out now.