In Hollywood’s beloved holiday blockbuster Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, protagonist Kevin’s worst fears come not from his bloodthirsty assailants—the self-proclaimed “Sticky Bandits”—but in the form of a homeless “Pigeon Lady” living in Central Park. As a child watching the film, I thought she seemed intimidating with her cloak of flapping birds, grubby face, and austere expression. However, as the movie unfolds, Kevin gets to know the Pigeon Lady (actual name notwithstanding), discovering a kind, gentle woman scarred by a tragic history of heartbreak and abandonment. Much like her feathered companions, she has faced rejection and chooses to live with them on the fringes of society. She acknowledges the similarity, explaining to Kevin: “Like the birds I care for, people pass me in the street. They see me but try to ignore me. They’d prefer it if I wasn’t part of their city.”

Touched by Kevin’s amity, her bitterness subsides and, in a climatic display, she unleashes her pigeon flock against Kevin’s pursuers. Overwhelmed by the winged warriors, the robbers are taken down and, consequently feathered, are arrested. To show his gratitude, Kevin later gifts her one of a pair of ceramic turtle doves, which he’s told by the toyshop owner signify everlasting friendship.

Like their cinematic counterparts, the common pigeon—that squat, ash-grey bird with a shimmering neckline and (if you’ve cared to look closely enough) striking orange eyes, whose ancestry is traced to the cliff-dwelling Rock Dove—is indeed a symbol of fidelity and friendship, owing to its loyal and affectionate nature. Yet, like the Pigeon Lady, it’s been cast aside by humans who have revered, bred, and even depended on the bird they once dubbed the “athlete of the sky” for thousands of years. Now, on a daily basis, these gentle birds are kicked at, shot at, poisoned, and kept at arm’s length by all manner of insidious spikes and nets.

So what happened to these affectionate, docile birds, which have shown humans such loyalty, tenderness and trust for millennia, now advocated for by a limited few and persecuted by so many?

Religious Symbolism

Pigeon symbolism runs deep through human history. The world’s oldest domesticated bird frequently appears across religious texts, where doves are famously a motif for peace and purity, idealized for their white feathers. However, doves and pigeons are all part of the same family, known as Columbidae. And as author Andrew D Blechman describes, the differentiation is all down to ‘linguistic bias.’ As he notes in his book, Pigeons: The Fascinating Saga of the World’s Most Reviled and Revered Bird, the word “dove,” in 14th century French, translates to “pigeon.”

Blechman explains that, although they’re essentially the same bird, the more delicate members of the Columbidae family are considered “doves” while the supposedly less graceful members are “pigeons,” giving rise to an old adage that “all pigeons are doves but not all doves are pigeons.” He gives the example that if a bigger pigeon (i.e. not delicate) is white, it may still be referred to as a “dove.” He continues: “Doves have come to mean petite and pure. Colloquial use of the word pigeon, on the other hand, emphasizes the dove’s docile nature and places it in a negative light.” Phrases like “stool pigeon”—which originates from the practice of tying pigeons to a stool to attract and trap predators—and “pigeonholed” are examples of how the word serves to describe inferiority.

In fact, Charles Darwin was among the first to demonstrate that the distinction between pigeons and doves is merely a biased interpretation of the same species. To support his argument for the theory of evolution, he selectively bred the birds in his backyard, often noting stark differences, like large fan-tails and feathery feet, all the while acknowledging their shared Rock Dove ancestor. He discussed his observations extensively in his famous 1859 work On the Origin of Species. Darwin’s fascination led him to join a pigeon fancier club, the Southwark Columbarium Society, in which members collected and bred “fancy” pigeons.

Pigeon illustration from Darwin’s “The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication,” Volume I, 1868.

Appearances aside, people have observed remarkable tenderness in pigeons for millennia, regardless of color or size. This trait is especially noticeable in their mating rituals. When a female pigeon wants a male to care for her, and ultimately their children, she places her beak inside his. By graciously accepting this gesture, the male is committing to his paternal responsibility. Blechman describes the sexual act itself as “very gentle and completely consensual,” followed by “affectionate cooing and preening of each other’s feathers.”

It’s this exchange of affection and responsibility of successful mating pairs which gives rise to pigeons’ role as a symbol for chasteness and purity in many cultures—as well as the idiom “billing and cooing,” used to describe couples showing affection (or “PDA” in today’s terms).

The birds also share parenting responsibilities, including egg sitting and feeding. And, if this doesn’t already present a glowing example of gender equality, both males and females secrete a milk-like substance, produced by prolactin—the hormone behind lactation—in their throats (or crops), which is fed to newborn squabs and is crucial to their development. Pigeons are one of only three birds, including flamingos and penguins, who nurse their young in this way.

It’s these qualities that earned the birds reverence in antiquity. Historical records, including on stone tablets in Mesopotamia (the area known as Iran and Iraq today) from 3000 BCE, indicate the birds were sacrificial assets and frequently offered to gods, while also serving as a food staple. In fact, the ubiquity of stone temples meant rock pigeons were right at home, while historic dovecotes—earthen houses for pigeons—date back some 2,000 years in Egypt, suggesting the birds were intentionally domesticated.

Pigeons’ fine parenting skills also cast them as symbols of fertility. The Babylonian goddess Ishtar, “Queen of Heaven and Earth and of the Evening Star,” was often depicted holding a pigeon or as the winged bird herself. The Phoenecian goddess of love and fertility, Astarte, was also represented as a pigeon, as were the Greek goddess Aphrodite and her Roman counterpart, Venus.

Pigeons also appear in Judeo-Christian narratives, most memorably, perhaps, in the story of Noah’s Ark in which a dove is sent to determine whether the floods have subsided. The dove—or white pigeon to today’s ornithologists—returns with an olive branch to indicate dry land. This is in contrast to the first attempt by a raven, which does not return.

Winged Messengers

As well as their significance as a harbinger of peace, the story of the pigeon’s return to the ark would be a mighty narrative coincidence if ancient civilizations had not picked up on the bird’s homing abilities.

5,000 years ago in Egypt, similar to Noah’s story, their earliest domesticated use is thought to be to warn people the Nile was flooded. According to Blechman, if the Nile was flooding, pigeons would be released and fly back home to let residents know. They were also used as messenger birds to announce the ascension of a pharaoh.

In the eighth century BCE, the ancient Greeks used carrier pigeons to deliver the results of the Olympic Games to villagers with a taste for gambling. Their presence at Olympic games lived on until last century when, at the opening ceremony of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, a flock of pigeons (referred to as doves) did not fly away as expected and were incinerated in the game’s Olympic cauldron.

In an episode of the British podcast series The Rest is History, BBC journalist Gordon Corera refers to Roman scholar Pliny the Elder’s writings in his Naturalis Historia about the use and value of pigeons in Rome and how, in 50 BC, a single pair of pigeons were sold for 400 dinari—about twice the annual wage of a Roman soldier. He describes their homing abilities as a “superpower”: “So you’re starting to see these birds can be incredibly valuable in civilizations where there’s a proper understanding of their homing abilities[…] these are creatures which are like a kind of superhero, they live among us and look normal and you don’t realize that they have this tremendous power. And, like any kind of superhero story, the science behind it is a bit wobbly.”

There are several theories exploring pigeons’ mysterious ability to navigate home from unfamiliar pastures—sometimes as far as 1,800 kilometers away. Visual cues, like landmarks and the sun’s position, along with smell, are usually considered to be the factors influencing their direction, but scientists also believe the Earth’s magnetic field helps a pigeon determine its bearings. This is, in part, due to the discovery of iron particles present in the beak. Another possible explanation is that pigeons create a kind of “sound map,” where they are guided by low-frequency sounds generated by the natural landscape. This theory emerged after geophysicist Jonathan Hagstrum became curious as to why 60,000 birds went missing during a long-distance race. His eureka moment arrived when he discovered a supersonic Concorde jet had disrupted their flight path, unleashing a sonic boom and throwing them off course. He explained: “When I realized the birds in that race were on the same flight path as the Concorde, I knew it had to be infrasound.”

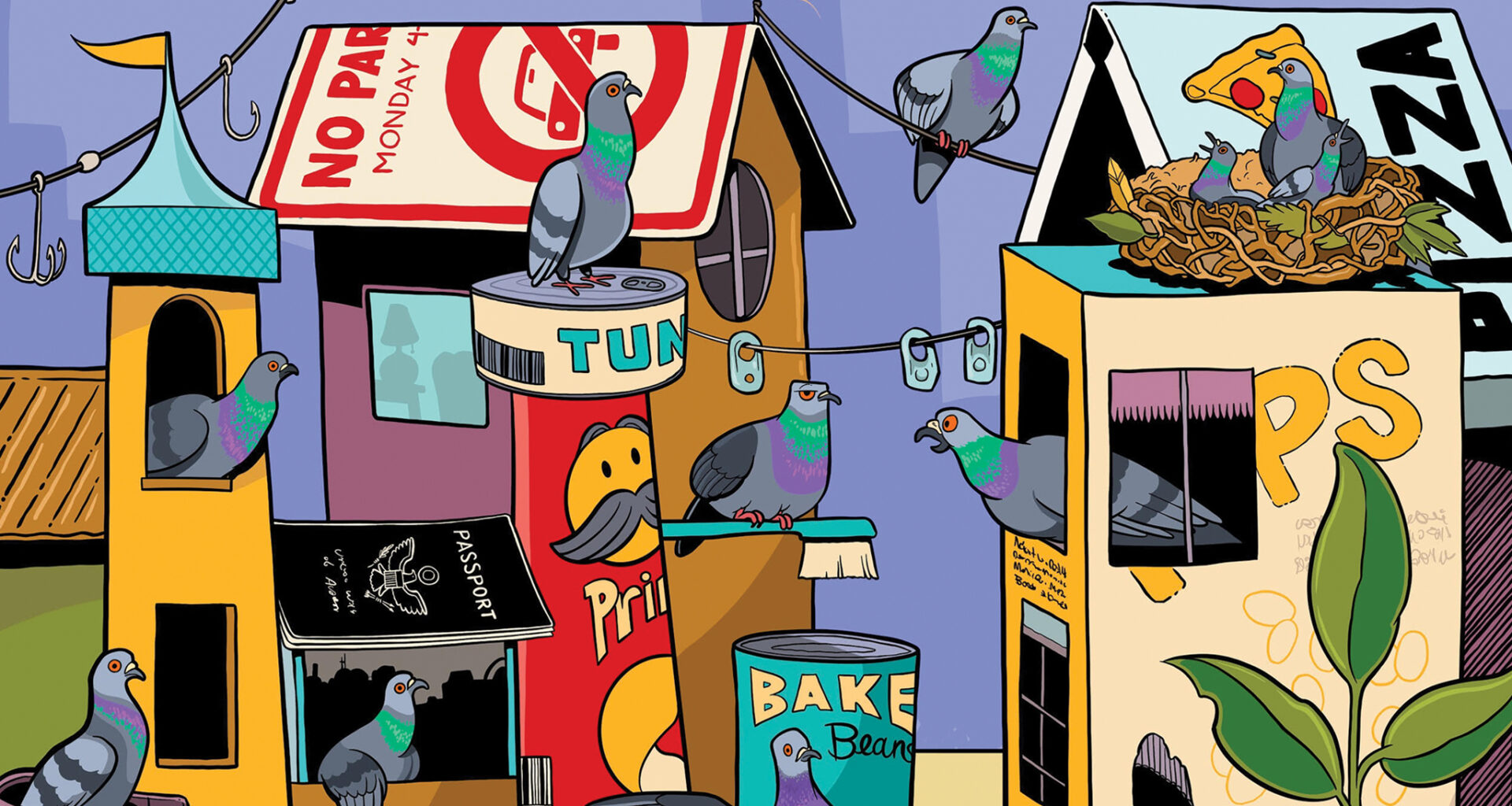

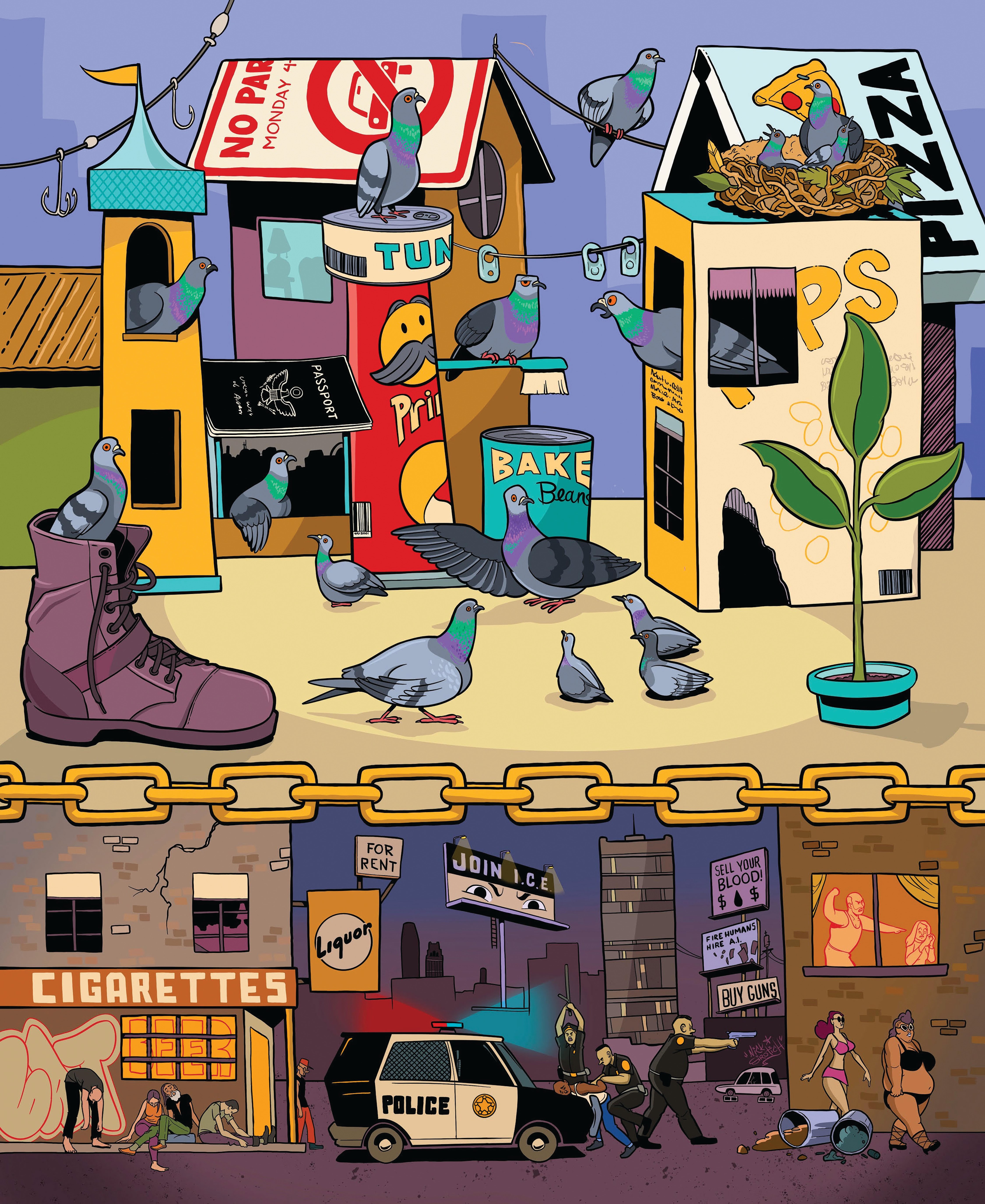

Art by Nick Sirotich from Current Affairs Magazine, Issue 55, September-October 2025

Art by Nick Sirotich from Current Affairs Magazine, Issue 55, September-October 2025

Pigeon Power

Throughout diverse periods of military history, pigeons have repeatedly proven their worth. Julius Caesar’s assassin Decimus Brutus and his adopted son and consul Aulus Hirtius are rumored to be the first to implement a pigeon postal system militarily, using the birds to communicate from the besieged city of Mutina during Mark Antony’s siege. Some 2,000 years later, homing pigeons were integral to the First and Second World Wars, where several were credited with saving hundreds of lives.

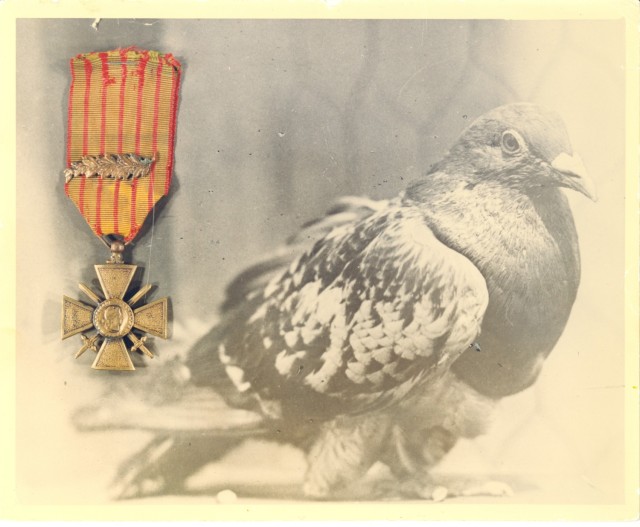

One notable example from WWI is Cher Ami, or “Dear Friend” in French. He was one of 600 Army Signal Corps pigeons deployed in that war, and the one who saved the 77th—or “Lost”—Battalion, which was cut off and trapped behind German lines without other means of communication. If that wasn’t bad enough, American bombs began mistakenly dropping on the 77th Battalion. The soldiers’ only hope was to send out an undetectable form of communication —a pigeon. Unfortunately the Germans were wise to the pigeon service, and Cher Ami proved a third-time charm after two before him were shot down.

U.S. Army Major Charles Whittlesey attached a note to the bird’s leg which read: “We are along the road parallel to 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake, stop it.” Though Cher Ami dodged several bullets, he did not escape fire and a shot through the chest sent him plummeting to the ground. However, by some miracle, he resumed his flight, covering 40 kilometers in just under half an hour. Following the successful delivery of the message, the bombardment ceased, and nearly 200 soldiers returned safely to America.

As for Cher Ami, he was treated by army medics, but lost his right leg and his vision. He became a testament to pigeons’ “superhero” qualities, and was awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French government for bravery on the battlefield. General John Pershing famously said of Cher Ami: “There isn’t anything the United States can do too much for this bird.”

The heroic bird died from his war wounds in July 1919, and his body was preserved. In 2021, on the 100th anniversary of his display in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, his body underwent DNA testing to resolve an enduring mystery surrounding his sex, which confirmed him male. And, yes, his body is still displayed today should you wish to honor Cher’s bravery personally. You’re welcome.

image: U.S. Army

image: U.S. Army

Athletes of the Sky

Unsurprisingly, pigeons lent themselves to a growing sport in the 1800s. Their renowned athletic and navigational abilities gave rise to pigeon “fanciers,” who selectively bred them for both racing and exhibiting. Pigeon racing originated in Belgium—where the world governing body Federation Colombophile Internationale (FCI) is situated today—making its way to the U.S. in the 1860s.

In a typical race the birds, which are identified by a tag around their leg, are trained to return to their loft from a starting point. The starting and finishing times are noted, and their speed calculated by dividing the distance by the duration of the bird’s flight. The distances involved vary from 100 up to 1,200 kilometers, known as a “Very Long Distance” race.

Known as “Homers,” these pigeons are supposedly the perfect iteration, cross-bred from varieties noted for two key attributes: physical endurance, and the ability to navigate home from great distances. The pigeon’s return is based on one or sometimes two factors—food and, if they are in a pair, a reunion with their paramour, in a controversial practice known as “widowing.”

While pigeon fanciers and breeders are often considered deeply attentive toward their flocks, it’s rarely without agenda. Separating a sentient being from their loved one so they are forced to fly thousands of kilometers for the sake of “entertainment” is one of several examples of the cruel treatment of the birds—so trusting of humans regardless of the abuse they face, both off and on the streets. As you might expect, some pigeons do not make it home, suspected drowned in the desperate bid to return to their mate.

To outsiders, the sport might seem like a quirky and harmless pastime. But its glamor cloaks a darker side of exploitation, cruelty and the kind of moral repugnance usually reserved for blood sports like fox hunting. As well as fatal exertion, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) has revealed cases of breeders shooting unwanted birds and using abusive training methods, often as part of a multi-million dollar gambling industry, in a 15-month undercover operation in the United States.

PETA’s investigators discovered that birds who aren’t considered fast enough or useful for breeding are usually killed by suffocation, drowning, neck-breaking, gassing, or decapitation. An article on its website entitled “Pigeons are Not Ours” includes the admission of one “world-renowned racer” who revealed they use just one out of 12 pigeons for breeding, before killing the rest and their offspring.

Perhaps just as grotesque is that the sport’s deep competitiveness means pigeons, like human athletes, are not immune to illegal drug enhancement. In 2013, reports of cocaine and painkiller use emerged in six Belgian birds. Investigators discovered traces of acetaminophen in five homing pigeons while cocaine was found in another. The discovery led to fresh calls for a crackdown on the practice, after which tighter rules and more robust enforcement were implemented in Belgium.

Whether this reform was out of concern for the pigeons or for the integrity of the game is uncertain, but let’s hope that unlike the birds themselves, the once-celebrated sport continues to decline.

Fall from Grace

As the popularity of pigeon racing began to dwindle, so too did humanity’s long love affair with pigeons. In the mid-20th century, the term “rats of the sky” became a common slur, courtesy of a New York City Parks commissioner Thomas Hoving, who used it when falsely linking them with a 1960s meningitis outbreak. The rumor was debunked, but the name remained, cemented in popular culture when it cropped up in Woody Allen’s 1980 film Stardust Memories. (As if there weren’t already enough reasons to dislike that guy.)

In 2005, sociologist Colin Jerolmack, author of “How Pigeons Became Rats: The Cultural Spatial Logic of Problem Animals,” trawled through 155 years worth of New York Times articles to better understand the human-pigeon relationship timeline. He believed Allen’s movie proved fatal for pigeons’ plummeting reputation. In the early 2000s, under ostensibly socialist mayor Ken Livingstone, London killed off the majority of its famous Trafalgar Square pigeons, starving them by banning people from feeding them and even introducing hawks to kill the pigeons, resulting in the square’s pigeon population declining from 4,000 to several hundred.

In an article for Audubon magazine, Jerolmack suggested that another explanation for pigeons’ swift fall from grace is their tendency to poop in vast quantities. According to the Southern Nevada Health District, an individual pigeon poops around 25 pounds a year—the weight equivalent of around two bowling balls. And since the feces is highly corrosive, over time it can cause structural damage to buildings.

Jerolmack explains that the effect contributes to a widespread belief that the birds are encroaching on our designated city space—places of orderly civilization as opposed to the nonlinear chaos of nature, where pigeons and their poop supposedly belong. As he puts it: “That doesn’t mean there’s no nature, but ideally, the city is the place where we invite nature in ways that we control. We cut out little squares in the concrete, and that’s where the trees belong. We don’t like it when grass and weeds begin to grow through cracks in the sidewalks, because that’s nature breaking out of those boundaries that we want to keep it in.”

These uniform ideals about who “belongs” and “doesn’t belong” apply to birds and humans alike. In cities around the world, property owners often place sharp spikes to keep pigeons away. They do the same thing to poor and homeless people, too, in the form of “hostile architecture”: spikes, bolts and railings, casually woven into the makeup of metropolitan areas to deter weary individuals seeking rest or shelter. This is seen in irregular shaped benches, awning with deliberate gaps in and, more overtly, in boulders under bridges, designed to push society’s outliers to its fringes—think back to Home Alone’s Pigeon Lady. It’s all the same underlying cruelty.

What’s a Bit of Poop Between Pals?

Almost two decades after Jerolmack’s paper, a controversial 16-foot pigeon sculpture known as “Dinosaur” occupies Manhattan’s High Line Plinth, a dedicated space reserved for contemporary art structures. The creator, artist Ivan Argote, told Smithsonian Magazine that pigeons are both “an icon of New York” and “a marginal creature living in dirty corners.” The statue’s name also points to their ancestry, since birds are considered a surviving descendant of dinosaurs. Argote also said he wanted the piece to evoke “an uncanny feeling of attraction, seduction and fear” among New Yorkers—a statement capturing the extremes of our love-hate relationship with pigeons.

In another gracious acceptance of the supposed city interloper, the London Museum caused controversy when, in 2024, it redesigned its logo as a pigeon complete with a glittery poop splat. Museum director Sharon Ament told the BBC the design celebrated the “gritty” reality of city life. “The pigeon and splat speak to a historic place full of dualities; a place where the grit and the glitter have existed side by side for millennia; an impartial and humble observer of London life.”

image: london museum

While it’s true pigeon feces can contain a fungus that, if inhaled, could lead to illness for a person with a poor immune system, disease expert Professor Mario Girolami argued the same germs are common in the air, soil, and among other animals. “Why pick on the pigeons?” he asked a New York Times reporter.

Pigeon rehabilitator Inese Struple, who began rescuing the birds near her London home during the Covid lockdown, described the very few cases of zoonotic transmission of disease from pigeons to humans as “negligible.” She added: “I’m part of a large volunteer network, mainly in the UK, but also internationally. I don’t know of a single rehabber who has contracted a disease from handling a pigeon.”

Inese is among the minds behind a creative solution for pigeon handlers to avoid their homes and aviaries being blighted by the dreaded droppings: pigeon diapers or “flypers,” which have a special pouch to collect them. The concept has spread widely among pigeon rehabilitators, with instructional videos showing how to make and put them on. One winged companion who has no need for such accessories is potty-trained “purse pigeon” Pidge, whose story went viral on TikTok. Brooklynite Abby Jardine adopted her, having found her as an abandoned orphan. Abby describes Pidge as a “blend of a cat and a dog,” only “weirder,” demonstrating her fondness for a neck tickle from her purse carriage.

Custodians Coming Together

It’s the city-slicking bird’s tender reliance on humans that has led to a growing network of people, like Inese and Abby, looking out for the so-called pests.

San Francisco-based Palomacy Pigeon and Dove Adoptions is a non-profit organization, which has been rescuing and rehoming pigeons since 2007. It has contributed to a global movement of pigeon rescuers, with a social media satellite group of some 42,000 members.

Pigeon custodians remain on the lookout for birds who find themselves victims of the urban environment. One of the most common issues they fall prey to is “stringfoot,” when string—from thread and fishing line to human hair and even dental floss—entangles their feet. If it’s not removed, they’re at risk of infection and even losing their foot altogether. Stringfoot removal groups have begun springing up across the U.S. and further afield, where volunteers share advice on dealing with the issue. Facebook lists eight formal groups in North America, with several more in the U.K. contributing to the grassroots movement.

Last year, Palomacy member Jennifer Morales came to the aid of a stringfoot victim found hanging upside down from a Los Angeles Sunset Boulevard sign in what was described as an “epic rescue.” The pigeon—later named Lotto—had human hair and a fishing line tangled around both his feet, which had caught on a bolt. After a solid four hours of wriggling, the stringy mass stripped the flesh from his legs, scoring into his shin bones. After the fire department and a tree trimming service refused to help, SMART Animal Rescue Team, a division of LA Animal Services, finally came to Lotto’s aid, stopping the traffic before reaching him with a cherry-picker.

The rescue organization, Moose’s Flock Pigeon and Dove Rescue, which took in Lotto, launched a fundraiser to pay for his medication and physical therapy. To date founder Jenna Close has raised an impressive $2,100 of the $3,800 target.

Talking about the extraordinary display of generosity, she said: “What impresses me most about pigeons is their resilience, and I think that is why Lotto’s story resonated so strongly across the globe. He went from nearly dead to using only one leg to using both legs and thriving. As a non-profit pigeon rescue, I help pigeons every day that really shouldn’t be alive, but there they are—badly injured, abused or both—and they are eating and drinking and hanging on until they can get help. And they do know when someone is helping them. They know when they are safe and they know when they are in good hands.”

While it’s not clear when the practice of de-stringing pigeons came about, the late British author Naomi Lewis is credited for her attention to the effects of human detritus on city wildlife. In the 1990s, Lewis ventured out to spots where pigeons gathered, coaxing affected birds with seed before capturing them and snipping tangled debris from their legs. But unfortunately, she was regarded as an “eccentric,” and there were few like her around in the late 20th century, when poison was a legal and acceptable form of flock control.

In 1972, a toxin—or avicide—known as Avitrol, was approved for use by the Environmental Protection Agency across the U.S. The substance fatally attacks the birds’ nervous systems, causing distress and convulsions.

However, in 2020, a woman named Bonnie Siegfried posted a video of a bird convulsing as she held it in her arms, and which later died. Similar cases followed, with pigeons reported plummeting from trees, distressed, twitching and dying. A necropsy found Avitrol was to blame. The poison has been banned in New York, Colorado, Portland and San Francisco, although the law is not always upheld; in 2012, reports of birds “falling from the skies” in Manhattan sparked suspicions over its prohibited use.

“Netting”—an anti-bird device designed to prevent them gathering in places they’re not wanted—might seem a tamer way of deterring pigeons, but the nets are well-documented to cause entrapment and suffocation. Last year, animal advocates spoke out after a number of pigeons were found tangled in netting on scaffolding on some Manhattan apartment buildings. Management said the measure followed a health violation due to “excess bird droppings,” feebly suggesting that holes cut to release trapped birds were encouraging more to nest there. Meanwhile, advocates pointed out the netting invariably caused more droppings due to all the trapped birds, and it was removed after multiple complaints.

Meanwhile, pigeon shooting as a sport is illegal in much of the Western world (in its early 20th century heyday it transitioned to clay-pigeon shooting surprisingly quickly), but Pennsylvania is still notorious for the controversial pastime in which captive pigeons are shot on release. A bill to prohibit the bloodsport was advanced this spring but tabled due to political and financial arguments. However, advocates remain hopeful it will be reintroduced during the next round of legislation.

While there are at least some of us looking out for wildlife’s urban underdogs, pigeons clearly don’t enjoy the status they once held. Perhaps there will come a day when, especially with people like Jenna, Ines and Abby filling a much-needed PR position—not to mention the rise of TikTok “pigeon propaganda”—people and pigeons can live contentedly side-by-side.

Just the other day, I stopped for an orange juice at a park kiosk. There, at the only available table, was a pigeon innocently hopping about with just one foot—I’m assuming the other fell prey to a tangle of human-derived detritus.

I sat marveling at the bird’s incredible resilience, wishing I had some pastry crumbs to afford them a moment of tasty respite. I sat for a while observing this pigeon until a staff member came and shooed them away. Obviously, I understood that she, like most of society, thought of the bird as a pest, shedding apparent contaminants around a place serving food. But it was a park and the pigeon, with its iridescent neck and varying grades of charcoal plumage, was causing me no bother. Happily, I saw them again when I revisited some days later, scampering about with a (two-footed) friend. I realized, with content, this must be their home—a place they gather with their flock and where, hopefully, some diners might spare them a few breadcrumbs.

Showing care to others—regardless of color, shape or species—is not weird or eccentric, it’s what makes us human. And it’s high time we afford the birds who’ve never stopped trusting in us, despite facing decades of persecution, at least a crumb of compassion or two.