Editor’s note: This story is part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and performance through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

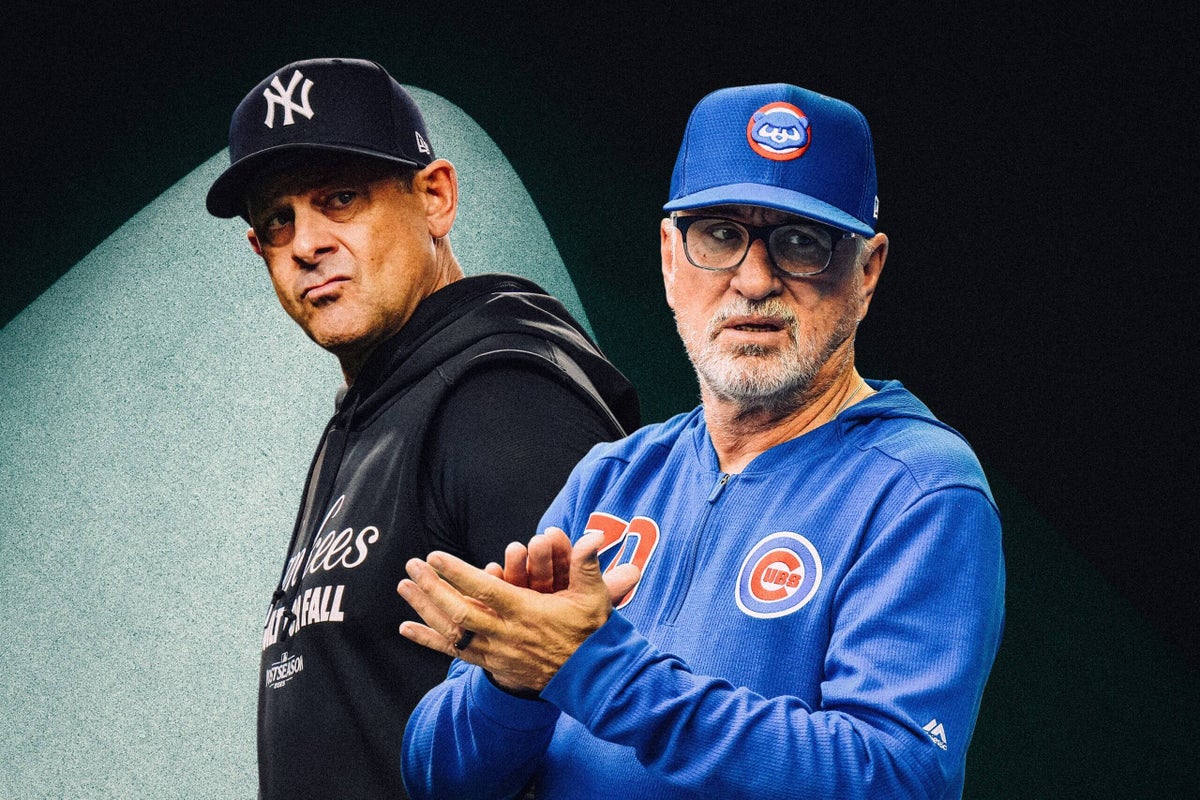

When Joe Maddon managed in the major leagues, he plastered his favorite saying on a hoodie: “Feel is the gift of experience.”

Maddon, 71, managed 2,666 games in his career, including 67 in the postseason, which meant he had a lot of experience. One of those moments happened to come in Game 7 of the 2016 World Series, when his Chicago Cubs were on the road in Cleveland, trying to end a 108-year title drought.

With the score tied 6-6 in the top of the ninth inning, the Cubs’ Javy Baez stepped to the plate to face Cleveland reliever Bryan Shaw. There was one out and a runner on third base. Baez, a notorious free swinger, had a history of waving at low breaking balls on 3-2 counts; Maddon had looked at the data and seen the numbers about how Baez performed in those situations. With the count full, Maddon had a flash of clarity: If Shaw threw a slider down in the zone, Baez would chase the pitch and strike out.

Maddon thought about Don Zimmer, the legendary baseball man who had worked alongside him years earlier with the Tampa Bay Rays. Zimmer prided himself on his feel and preached the same message to Maddon: If it comes into your mind, you do it.

“I swear to God it was a hot moment in the World Series and I said, ‘Oh my God, Zim’s speaking to me from the grave right now,’ ” Maddon said.

So he did the unthinkable: He asked Baez to bunt with two strikes, hoping to score the runner from third with a safety squeeze.

For Maddon, it was pure intuition — a blend of data, experience and expertise coming together in an instant. Then the pitch came, Baez bunted foul, and he was out on strikes.

“Intuition failed me,” Maddon said. “But I really thought it was the right thing to do in the moment.”

Consider the decision a Rorschach test. Was Maddon’s gut call a misguided mistake or a case of intuitive decision-making that didn’t work?

It’s a debate that reappears each October as baseball managers walk the playoff tightrope. Every game offers dozens of tactical choices — lineups, bullpen usage and the occasional safety squeeze. The sample sizes are tiny, but the outcomes are not.

In the era of big data, decisions are often shaped by front-office analysts and statistical models that map out plans and matchups before each game. Thus, the age of sabermetrics presents an easy debate: data vs. gut.

But for researchers studying decision-making, the role of data is not at odds with intuitive decision-making. In fact, it’s at the core of it.

“Intuition and data are often framed as if they’re opposites,” Dr. Jennifer Lerner, a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School, said in an email. “But research shows that intuition is often the distillation of years of experience with data and patterns.”

The concept of intuition is often misunderstood, seen as biased by impulse, emotion or heuristics — mental shortcuts that allow for quick decisions — or as a mystical quality of discernment that only some possess.

Instead, it’s often a vital part of the decision-making process. Lerner has taught fire chiefs, who must rely on intuitive feel when managing a strategy in a chaotic, unpredictable blaze. The “gut feel” they use is not simple guesswork but rather grounded in decades of experience, enabling them to recognize a situation and respond more quickly.

“By contrast, they view it as dangerous when a rookie firefighter trusts their gut,” she said. “Without sufficient experience, what feels like intuition is often just bias or noise.”

There are no perfect decisions in October. Baseball is too unpredictable; the variance is too high. Yet the challenges managers face can reveal something about how we make decisions.

Before Game 1 of the 2015 World Series, Kansas City Royals manager Ned Yost penciled in shortstop Alcides Escobar at the top of the batting order. On paper, it was an odd move. Escobar was an undisciplined hitter with an on-base percentage under .300 and an OPS in the low .600s. Not exactly leadoff hitter material.

Yost knew the numbers; they were delivered before each series via a three-ring binder by the club’s analytics staff. During the regular season, he had even tried to move Escobar down in the lineup. But over the course of two years, including the 2014 postseason, the Royals won 63 percent of their games when Escobar led off and around 50 percent when he didn’t.

The way Yost saw it, he was doing what made sense.

“I didn’t feel like it worked,” Yost said. “It worked. I felt like that was right, and I didn’t care what anybody said.”

In Game 1 against the New York Mets, Escobar led off with an inside-the-park homer.

The case of Escobar illustrates a fascinating contradiction about intuition touted by Laura Huang, a professor of management and organizational dynamics at Northeastern University. When decision-makers or business leaders try to explain their gut feeling, they often end up talking themselves out of a decision.

For instance, if Yost had tried to validate the Escobar move using rational logic, he might have been more likely to default to the numbers or make a safer choice.

As Huang likes to say: Intuition “whispers” while data “screams.”

“We’re not very good at listening to what whispers,” she said.

Huang, an engineer, began studying intuition while earning her doctorate at the University of California, Irvine. She received pushback from scholars, who believed the field was a dead end. She was told it was “an atheoretical line of questioning,” meaning it would be hard to test.

Huang began with a dissertation on “the impact of gut feel on entrepreneurial investment decisions.” What she found intrigued her; she followed it up with a 2025 book, “You Already Know: The Science of Mastering Your Intuition.”

Huang argues that people should disentangle the ideas of “intuition” and “gut feel.” In her view, intuition is better viewed as the process — the subconscious combination of data and experience, or what Huang calls the “vast reservoir of pattern recognition, emotional memory and contextual fluency.” The resulting judgment, Huang says, is “gut feel.”

Royals manager Ned Yost bucked convention when he decided to hit Alcides Escobar (No. 2) in the leadoff spot in the 2015 World Series. (Dilip Vishwanat / Getty Images)

In the MLB postseason, most managers try to tame the unpredictability through preparation. The process includes data analysis and modeling, seeking out the best matchups using advanced metrics, down to granular data like pitch shape and a player’s swing path. The preparation, of course, requires its own form of intuition. Someone has to decide which metrics will be most useful.

“There’s ideas,” Cubs manager Craig Counsell said earlier this month. “Not firm plans.”

When Yost managed the Royals in the playoffs in 2014 and 2015, he sat down with his coaching staff and mapped out games in advance, a process designed to eliminate on-the-fly decisions. He preferred rigid bullpen roles, no platoons and few pinch hitters.

“When a situation would pop up,” Yost said, “we already knew what we wanted to do.”

For other managers, a postseason game requires thinking like a chessmaster. When Terry Collins managed the Mets in the 2015 postseason, he recalled a line he heard from Hall of Fame manager Jim Leyland: “Managing is about being two innings ahead of the other guy.”

In Game 4 of the National League Championship Series that year, as the Mets closed in on an NL pennant, Collins called on 42-year-old starting pitcher Bartolo Colon to face Kris Bryant, the NL Rookie of the Year, with two runners on base in the bottom of the fifth. It was an unlikely spot for Colon, but Collins had a feeling.

“It’s just those instincts about, ‘Hey, look, I think Bartolo’s the guy for this instance,’ ” he said. “I knew he was probably going to hit it, but I knew he’s also gonna hit it on the ground.”

Colon ended up striking out Bryant.

There are plenty of instances of managers seemingly defaulting to data. In the 2020 World Series, Tampa Bay Rays manager Kevin Cash famously pulled starter Blake Snell after 5 ⅓ scoreless innings. Snell had thrown only 73 pitches and struck out nine, but the top of the Los Angeles Dodgers lineup was ready to face Snell for a third time.

“I felt Blake had done his job and then some,” Cash said then.

Earlier this postseason, Yankees manager Aaron Boone faced similar scrutiny when he pulled starter Max Friend after 6 ⅓ scoreless innings and 102 pitches in a loss to the Boston Red Sox. The criticism was built on previous postseasons, when Boone was judged for being too pre-programmed.

In Game 2 of the 2019 ALCS against Houston, Boone aggressively pulled starter James Paxton after 2 ⅓ innings, unleashing a parade of relievers. As Yankees reliever Chad Green was cruising through six batters — recording 21 strikes in 26 pitches — the Yankees had already mapped out the following pitching change.

Before Green even struck out Kyle Tucker to begin the fifth, reliever Adam Ottavino had been told he would face the next hitter, Houston’s George Springer.

The Yankees followed the script, and Springer hit a game-tying solo homer in a game the Astros won in 11 innings.

“The game is not a big picture,” Maddon said. “The game is a small-sample size. That’s where you have to rely on the experience of your group.

“It could be boldness. It could be being able to see things in advance. It could be reading faces. It could be sensing the mood. It could be the pitching coach saying the starter doesn’t have his stuff, so be on alert. All that is feel and that is the gift of having done it before, often.”

Intuition, researchers say, is not a cheat code.

Nobel prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman proposed that people have two different thought systems. The first was fast, spontaneous and intuitive; the second was slower and more rational. The rapid system, Kahneman wrote, was less reliable.

In the early 2010s, a pair of German economists set out to study whether experience mattered — whether years of study and expertise determined whether rational decision-making or intuition was more effective. The economists, Marco Sahm and Robert K. von Weizsäcker, grew up playing chess.

When they were young, they played intuitively, cataloging the moves and styles of others, then incorporating them into their games. But as they grew older, they discovered chess theory, read strategy books and used the data to adopt an analytical style. The experience influenced their work, which attempted to use a mathematical model that analyzed the cost-benefit of each method.

Sahm emphasizes that the purpose was to show how decisions are made, not to provide advice on how they should be made.

“Once you start thinking whether you should decide rationally or intuitively, you have already started reasoning,” he said in an email.

Their findings were illuminating: On the whole, rational decisions are more precise, but they entail higher costs, such as time and the energy required to analyze information. However, experience can close the gap. Once a person has had enough encounters with related problems or similar decisions, intuitive decisions can be faster and effective.

The model, Sahm said, could be applied to “many processes of decision making in the real world.”

It’s rare, of course, that people make decisions without using data and intuition at the same time. Lerner, the Harvard professor, believes “the best leaders are likely those who integrate the two modes.”

Meanwhile, Huang believes managers can refine their intuition through both years of experience and tools such as structured reflection (“what did I miss?”) and what she calls the “calm test”: Would I make this decision if I were completely calm?

For Maddon, the latter was crucial during big playoff games. He never wanted to be afraid to go off script — or stick to it.

In the 2015 NL Wild Card Game in Pittsburgh, Cubs ace Jake Arrieta was facing Pittsburgh’s Gerrit Cole in a winner-take-all matchup. Arrieta was dominant, entering the ninth inning with a 4-0 lead and having thrown 103 pitches. Maddon thought back to a game with the Midland Angels in the mid-1980s, when he pulled his starter with a 3-0 lead, inserted his closer, and lost.

“Traditional methods are not always right,” Maddon said, and so he sent Arrieta back out for the ninth and sent word to the bullpen: Be on alert.

He had a feeling. Arrieta pitched a scoreless ninth. The Cubs won 4-0, their first playoff win on the way to an NLCS appearance.

That time, Maddon’s intuition worked.