If you’re watching a scary movie and things get too intense, you’ve got options. You can cover your eyes and plug your ears, hit fast-forward, or even step outside. But scary books require your active participation. These characters need you to turn the page for their plot to progress — and there’s an unspoken pressure that you, the reader, press on to resolve their pain.

Literature gets its most terrifying qualities by manipulating a kind of fear only the written word can spur within you. Truly upsetting books reward and punish their audiences for remaining curious, creating the same “can’t look away” energy you get driving past a car accident or stumbling onto an extreme viral video. It’s a tall order working against a storytelling medium that, for better or worse, sometimes suffers because it’s seen as labor-heavy. And yet, there are the legends who pull it off and spend the rest of their lives reaping rewards.

Stephen King remains one of the most adapted horror writers in history, and his stories continue to break new ground for Hollywood each year. In 2025, Lionsgate brought what’s technically King’s first book (published using the name Richard Bachman more than a decade after it was written, when he was only 19) to the big screen. Attempted by legends from Romero to Darabont, “The Long Walk” was once considered unadaptable. But director Fancis Lawrence and screenwriter JT Mollner disproved that theory and delivered a hit at the box office.

As mysteries grow murkier and victims descend deeper into hell, the most skilled genre authors know how to properly razz their readers with a delicate balance of satisfaction and shock. The alchemy that can make a scene scary in a book doesn’t always translate for a film or TV show, but it has in plenty of cases and there’s a lively conversation to be had whenever that transmutation successfully convinces fans of different formats to swap places.

With Guillermo del Toro’s stylish spin on “Frankenstein” coming to theaters this October — and an episodic adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ “The Shards” keeping our eyebrows raised toward the horizon — IndieWire’s bravest bookworms have drawn up a list of the scariest written stories we want to see retold on film or TV. Novels, short stories, internet creepypasta, and more formats qualified for this list, so long as the nightmare hadn’t been tried on screen before.

With editorial contributions by Ryan Lattanzio, Wilson Chapman, Sarah Shachat, and Christian Zilko.

“I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” by Harlan Ellison (1967)

Image Credit: Amazon/Audible

It would take the fine-tuned visual depravity of an artist like “Mad God” auteur Phil Tippett — and possibly the influence of some heavy historic acid cinema, whatever that means to you! — to bring Harlan Ellison’s skull-crushing short story from 1967 to life. But done correctly, “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” wouldn’t just be “worth it” for the right Hollywood studio. No, this is the kind of sci-fi horror story that is so bone-deep, turn-you-inside-out scary that the right rendition of it might just get a few reckless tech moguls and evil business tycoons to rethink the A.I. apocalypse they’re presently unleashing on all of us. (Shut up, I’m allowed to dream!)

Brief but brutal, this dystopian nightmare leaves the fallout of World War III to the whims of a spiteful supercomputer that’s taken just five surviving humans hostage to make an infinite point. Known as “AM” (short for “Allied Mastercomputer”), the all-consuming antagonist ripples through the techno-underworld its victims inhabit — creating a maze-like narrative that makes the reader feel trapped, too. Ellison himself was involved in creating the 1995 video game that helped further popularize the concept, but we have yet to get the cinematic take on this story that the singularly screwed meat-sacks in it deserve. —AF

“Three Skeleton Key” (CBS Radio’s “Escape!”, 1950)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection

Originally a short story by French author Georges-Gustave Toudouze, “Three Skeleton Key” is likely better known as a 1950 Vincent Price-led radio play produced by William N. Robson for “Escape!” The exclamation point should give you a sense of the tone. The plot sits at the center of a very rare Venn Diagram of Robert Eggers’ “The Lighthouse” and that scene in “Ratatouille” when the humans come in the kitchen and all the rats run away in different directions. The story centers on three lighthouse keepers, isolated at a lonely tower on the coast of French Guiana, a grim place notorious for a group of convicts who once died there leaving behind only bones. It is an inhuman menace, however, that torments our heroes, as they’re slowly forced to the top of the lighthouse by — and this is really what happens — an endless, undulating carpet of enormous, flesh-hungry rats.

Now, in audio, aided and abetted by Robson’s sound effects and Price’s ravenous narration, this premise gets to be properly scary. The swarm is never undone by having to visually define the mad rats. They can be as big as the characters’ fear of them, in our minds. But it’s an interesting challenge for a short or a feature film. How do you keep up the paranoia and suspense, maybe even do a highly pressurized character work, when the antagonists are Eldritch Rizzos? It’d be fun to find out. —SS

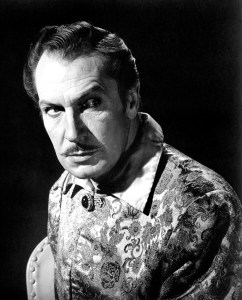

“The Twenty Days of Turin” by Giorgio De Maria (1975)

Image Credit: Liveright/Amazon

Giorgio de Maria’s Italian novel “The Twenty Days of Turin” was first published in 1975, but it’s quickly becoming one of the literary cult classics of the 21st century thanks to a 2016 English translation that brought it to audiences across the Atlantic. And in the hands of the right director, a feature film could be the natural next step that permanently enshrines it in pop culture.

The book toes the line between magical realism, serial killer brutality, and straight-up paranoia, telling the story of an Italian mental hospital that decides to add a creepy new feature known as The Library. It doesn’t contain any novels or published works of nonfiction: it exclusively carries the journals and private writings of real citizens, which anyone is allowed to read for free. Even worse, the identities of the writers are all available to purchase. The 24/7 access to everyone’s most intimate private thoughts begins to turn the town insane (who would have thought?!), and what begins with widespread insomnia turns into a bloody streak of murders. It’s not hard to see the parallels between The Library and the information-overloaded world that humanity would grow into, and a film adaptation of “The Twenty Days of Turin” could be cathartic for audiences lamenting the fact that doomscrolling is keeping them up at night. —CZ

“Come Closer” by Sara Gran (2003)

Image Credit: Faber & Faber

Sara Gran’s razor-sharp novella from 2003 would be fascinating as a psychological horror film, but its inventive structure and brilliant character work could be even better as a TV show or video game. So, let’s make one — or wait, both! And change the endings for each!

“Come Closer” inverts the movies’ typical approach to demonic possession by intertwining the fraying first-person perspective of a possible haunting victim (read: unreliable narrator) with the unraveling edges of her maybe-supernatural reality. The sound of mysterious tapping inside our heroine’s home doesn’t alarm the young architect at first. But with flecks of “The Yellow Wallpaper” shining through that faux-calm almost immediately, the noise soon drives Amanda into a sort of crazed self-demolition.

Countless authors and filmmakers have asked, “Is this chick cursed… or just crazy?” But Gran uses text-within-text to present the audience with a self-assessment for spiritual hijacking that feels like a direct indictment. “Come Closer” renders the feeling of evil lurking within you through a challenging style that’s at once profoundly personal, wildly unpredictable, mostly fresh, and genuinely frightening over 20 years later. Not to mention, the last line in this 150-page wonder is a total heartbreaker. —AF

“The Buffalo Hunter Hunter” by Stephen Graham Jones (2025)

Image Credit: Amazon/Audible

He’s released well over 30 books since 2000, but horror author Stephen Graham Jones has never seen his work get a film or TV adaptation. There’s a lot of potential in his stories, which often tackle classic horror conventions from an Indigenous American perspective. Several are suitable for a film, but his latest novel is also his best. Released in 2025, “The Buffalo Hunter Hunter” is a chilling historical thriller written from the perspective of a 1912 Lutheran priest’s diary, as he recounts the life of a Blackfeet vampire who haunts the fields of a reservation looking for justice after a forgotten massacre. It’s easy to imagine the novel’s period terror working well on screen as a haunting movie that mixes brains with frights. —WC

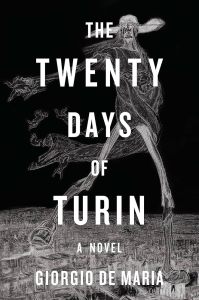

“Revival” by Stephen King (2014)

Image Credit: Scribner/Amazon

There’s really no such thing as a bad Stephen King novel, so I’ll be elated if he keeps releasing a 6/10 book every year for the rest of his days. But if we’re going to argue the topic of the last truly great King outing, or the best King book that remains completely unadapted, I would throw “Revival” into the mix. The 2014 novel tells the story of a Methodist minister who’s a little too interested in electrical experiments. What begins as using powerful electric shocks to treat the sick and disabled evolves into a full-fledged religious revival tour, leaving a trail of drug addiction and religious trauma in his wake. Charles Jacobs would be an iconic role for the right actor, and the part could be an ideal heel turn for someone with a squeaky clean image who wants to show another side of himself. It’s no surprise that Mike Flanagan tried to adapt the book for Warner Bros., but given that the project was all but declared dead in 2020, another studio or filmmaker should try to apply a defibrillator to it. —CZ

“The Dionaea House” by Eric Heisserer (2004-2006)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection

With A24 adapting the liminal-space-laden “Backrooms” into a feature film soon, creepypasta could finally get its due in the coming years. Yes, Sony fumbled “Slender Man” badly in 2018, and even the most passionate indie horror directors can’t seem to make a movie version of “The Russian Sleep Experiment” that doesn’t suck. But if there’s any chance of seeing “The Dionaea House” come alive in a theater — where fans were told this deeply disturbing viral short story would be long ago! — it needs to happen as fast as that tricky creative pipeline gets cleared.

Academy Award-nominated for the sci-fi drama “Arrival,” Eric Heisserer is also known for the smash-hit horror movie “Bird Box,” which was extraordinarily popular on Netflix at the tail-end of 2018. Both of those scripts were adaptations, but as a creepypasta writer, Heisserer left his mark on the form imagining a slippery haunted house — one that drives a man mad before sending another missing. It’s endlessly vast yet one of a kind, and if you find the right version online, you can explore its surprisingly dark and complex story for yourself.

An incomplete set of emails, presented to the reader as a multi-authored LiveJournal, “The Dionaea House” begins as a possibly supernatural missing person’s case. After your first readthrough, Heisserer’s bleak-yet-brilliant puzzle reasserts itself as a confounding vehicle for apocalyptic imagery and existential emotion that practically demands to be “solved.” The source material was optioned by Warner Bros. shortly after the story got popular online, and yet no one has managed to crack the case yet. Considering how it “ends,” maybe that’s for the best? —AF

“House of Leaves” by Mark Z. Danielewski (2000)

Image Credit: Amazon/Audible

Mark Z. Danielewski’s terrifying leviathan of an experimental novel “House of Leaves” was so influential in 2000 that it led his sister, the indie singer/songwriter Poe, to release a companion album called “Haunted” later that year. The 700-plus-page book — which often demands you hold it up to a mirror to read its backwards or upside-down text — remains one of the widest-read works of postmodern literary fiction of the 2000s, and one of the most difficult to adapt. In fact, Danielewski has said he would never allow someone to adapt “House of Leaves,” but with the right filmmaker, anyone is persuadable.

An adaptation would involve truncating or condensing the many layers in the book: First is an account of a found-footage documentary called “The Navidson Record,” one apparently distributed by the Weinstein brothers. The creepiest of the book’s passages follows a photojournalist and his family who move into a house in Virginia, only to discover it’s bigger on the inside than the outside dimensions suggest. And keeps getting bigger, more cavernous, as hallways and rooms appear overnight, floorplans shift, and an endless labyrinth opens up that the photographer and a group of friends set upon spelunking to terrifying ends. Beneath it is a low growling noise that appears to be the sound of the house shifting, growing, or something worse.

Layered over the text is a study, mostly told in footnotes and citations, by a blind academic named Zampanò. A disturbed man named Johnny Truant, living in Hollywood, discovers Zampanò’s text and is driven mad himself by the materials.

Were a filmmaker to tackle “House of Leaves,” stripping the book down to its deeply unsettling “Navidson Record,” as a found-footage horror film, would make for an eerily effective entry into the genre. What’s scarier than realizing the home you think you live in is not a home at all, but a living, expanding entity that wants to swallow you, your family, your dreams whole, and feed off your nightmares and fears? —RL

“The Thing on the Fourble Board” — (“Quiet, Please,” 1948)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection

OK, this one is cheating a bit. I, Sarah Shachat, do not actually think “The Thing On The Fourble Board” is adaptable from its original form as a radio play for “Quiet, Please,” written and directed in 1948 by the great Wyllis Cooper and acted mainly by Ernest Chappell. I do not think that because “The Thing On The Fourble Board” is one of the best pieces of horror radio ever produced. The story, about an oil rig worker who has an encounter with a mysterious… something from deep below the Earth, leans into the strengths of audio storytelling. The narrative gives you just enough detail for your imagination to hang yourself with, at a pace that just tightens and tightens like a nose. It involves the listener, too, as only audio can. I hesitate to write anything more about it. You should just listen to it.

And that’s my point. The Golden Age of Radio is much, much vaster than “The War of the Worlds.” Shows like “Escape,” “Quiet, Please,” “The Mysterious Traveler,” “Lights Out,” and others have roughly a bazillion great stories that could make interesting leaps into film. Some of them can’t work in a visual medium — if anyone can visually solve the twist of “SOS,” where the account of three people we spend 20 minutes believing to be shipwrecked sailors turns out to be a shipwreck IN SPACE, please make that happen — but a lot of them can. Please, guys. Go find Arch Oboler’s “Chicken Heart” and do something with it instead of another True Crime series. —SS