Art

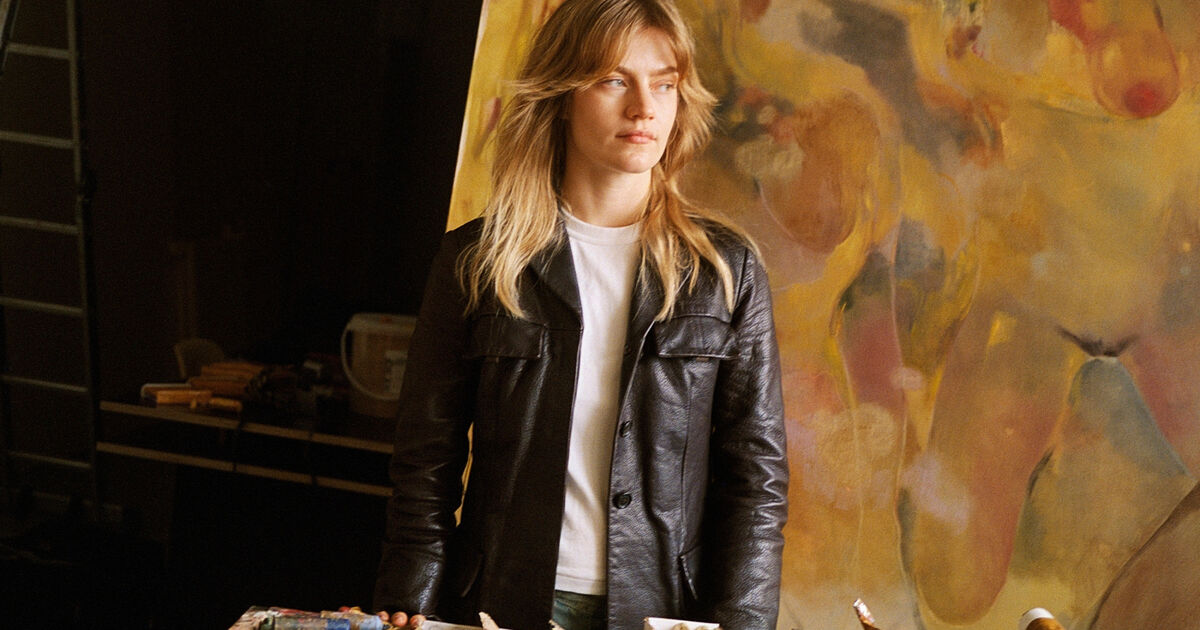

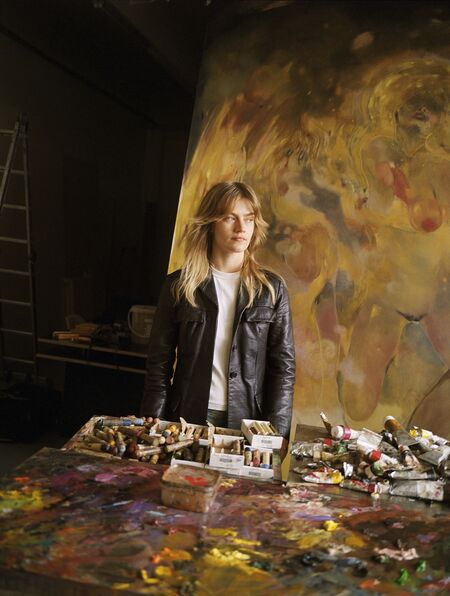

Portrait of Eva Helene Pade. Photo by Petra Kleis. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac.

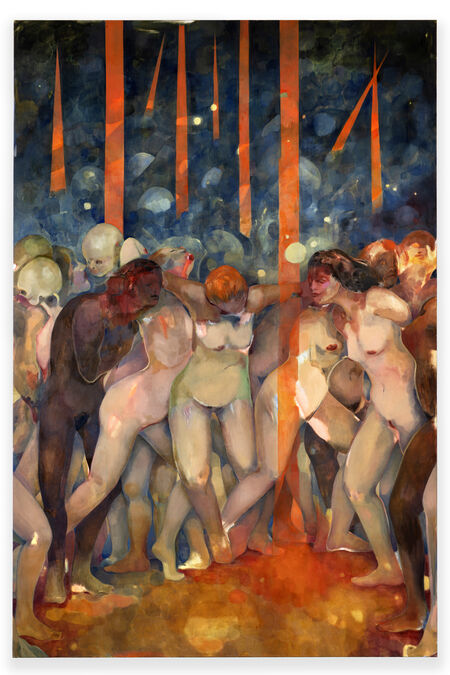

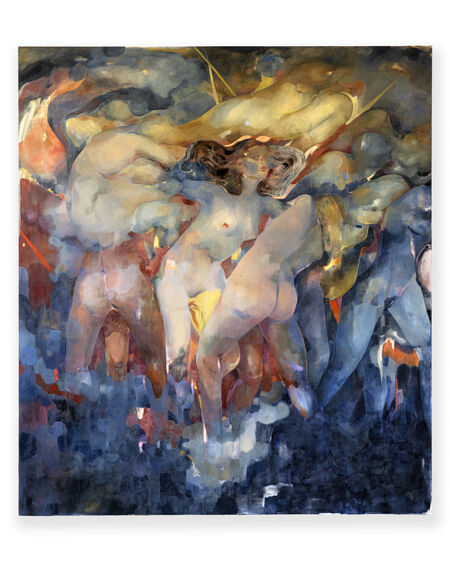

Eva Helene Pade, Rød nat (Red night), 2025. © Eva Helene Pade. Photo by Pierre Tanguy. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

The static medium of painting can feel a bit dissatisfying, according to Danish artist Eva Helene Pade. “It’s like a disappointing animal that doesn’t want to do all the tricks,” she quipped, “but it does so much—you could also say it doesn’t need to do more.” Pade’s latest paintings, however, do a little bit extra. Her dramatic command of balance and light charges her sprawling scenes with electrifying tension. Though still very much paintings, they actively teeter between anguish and ecstasy.

Last fall, Pade became the youngest artist represented by the major art gallery Thaddaeus Ropac. This week, she opens her first solo show with the gallery at its historic Ely House outpost in London, fresh on the heels of “Forårsofret” (The Rite of Spring), her star-making debut institutional show at the ARKEN Museum of Contemporary Art. Pade’s London show, titled “Søgelys” (searchlight), on view through December 20th, will present a rare smattering of small works alongside her signature monumental paintings.

Pade grew up in the quaint Danish city of Odense and earned her BFA from The Danish Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen in 2021. She signed with Galleri Nicolai Wallner, which still co-represents her, before even finishing her MFA at the same academy last year. But, around the time of her first solo show with Wallner, in 2022, Pade’s work began shifting. The defined figures of earlier works (like A Story to Be Told #14, 2021, which set her auction record last November) gave way to softer edges. By the time “Forårsofret” opened at ARKEN, Pade had found her voice.

Eva Helene Pade, På række (In line), 2025. © Eva Helene Pade. Photo by Pierre Tanguy. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

Time can make all the difference, she explained: “You have less you need to prove, so everything doesn’t have to be as stylized, and you become better at expressing what you want to say, faster.” Moving to Paris in 2023 helped too. “I didn’t feel challenged,” Pade recalled of Copenhagen, her previous home base. “I spent time in my studio but without feeling the energy that needs to be there.” Upon relocating, she painted in her flat—until she found a workspace in the suburb of Pantin where she and her neighbors host rooftop barbecues. That lofty new studio also empowered Pade to work in the large scale she prefers—the central paintings in “Søgelys,” for example, are around 8 feet tall and 9 feet wide, proportions often associated with history paintings.

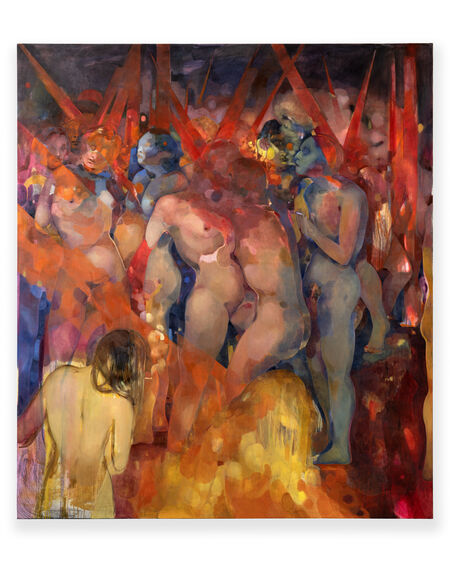

Paris also got Pade into dance. “I’d always gone to the opera or classical music, but I never really did the ballet,” she said. “That’s become a bigger part. Also, watching more performance art.” Whereas painting is decidedly two-dimensional, dance, theater, and music occupy time and space—realms Pade now aims to breach with her paintings. Rather than simply hanging on the wall, her 10 canvases in “Forårsofret” stood freely throughout ARKEN’s subterranean gallery on metal stands. Each one offered a narrative vignette from German choreographer Pina Bausch’s take on Igor Stravinsky’s 1913 ballet The Rite of Spring, which infuriated viewers with its dissonant choreography and pagan subject matter.

Eva Helene Pade, Knækkede stråler (Broken rays), 2025. © Eva Helene Pade. Photo by Pierre Tanguy. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

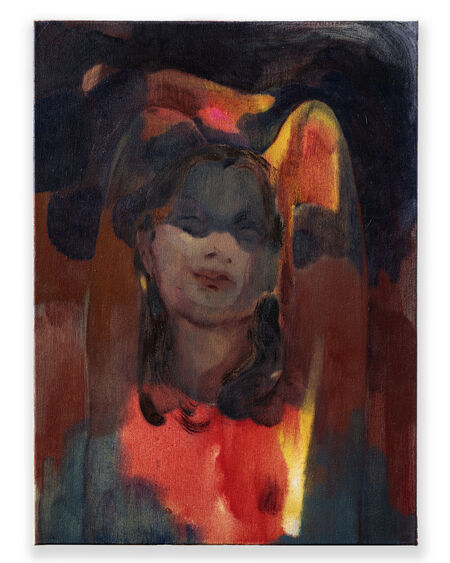

Eva Helene Pade, I mørket (In the dark), 2025. © Eva Helene Pade. Photo by Pierre Tanguy. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

Spotlights trained on those 10 artworks illuminated the backs of the paintings for guests weaving through “Forårsofret” who performed their own choreography. The artist found it fascinating that her initial markings shone through so decisively, displaying her works’ beginning and final stages at once. “That became, now, a thing I would like to do more,” she said. As such, she’s presenting “Søgelys” in a similar fashion, perching works on ceiling-to-floor metal beams throughout Thaddaeus Ropac’s 18th-century venue.

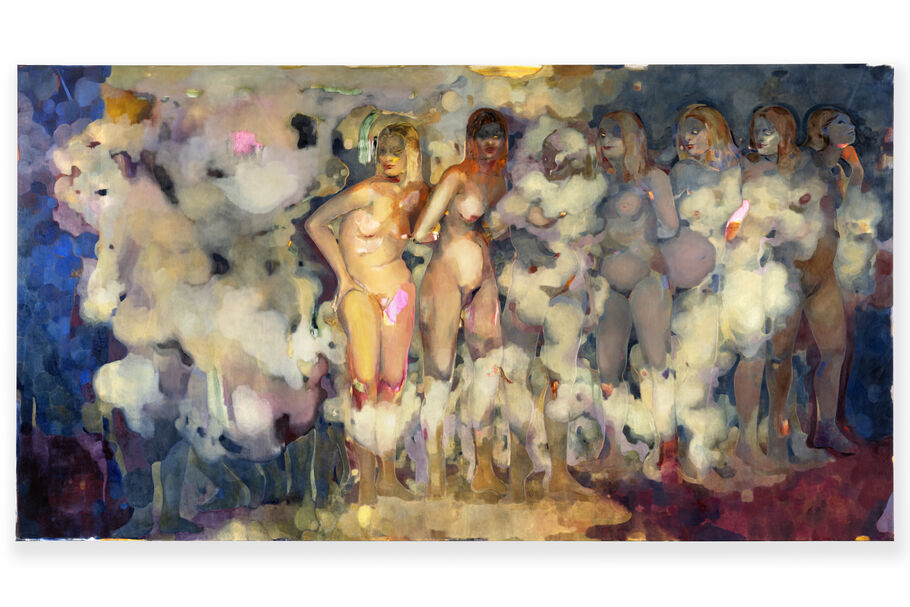

Pade’s ARKEN show also got her interested in the symbolic potential of smoke. Over the course of her ascendant career, she’s earned a reputation for well-placed art-historic references, evoking the Expressionism of German painter Otto Dix and the golden haze of Vienna Secessionist Gustav Klimt alike. “Some of it is conscious, and some of it is unconscious,” Pade commented. In “Forårsofret,” her work Forfædrenes ritual (Ritual of the Ancestors) (2024–25) outright riffed off French Impressionist Édouard Manet’s rendition of the bloody conclusion to French colonialism in Mexico, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867–69).

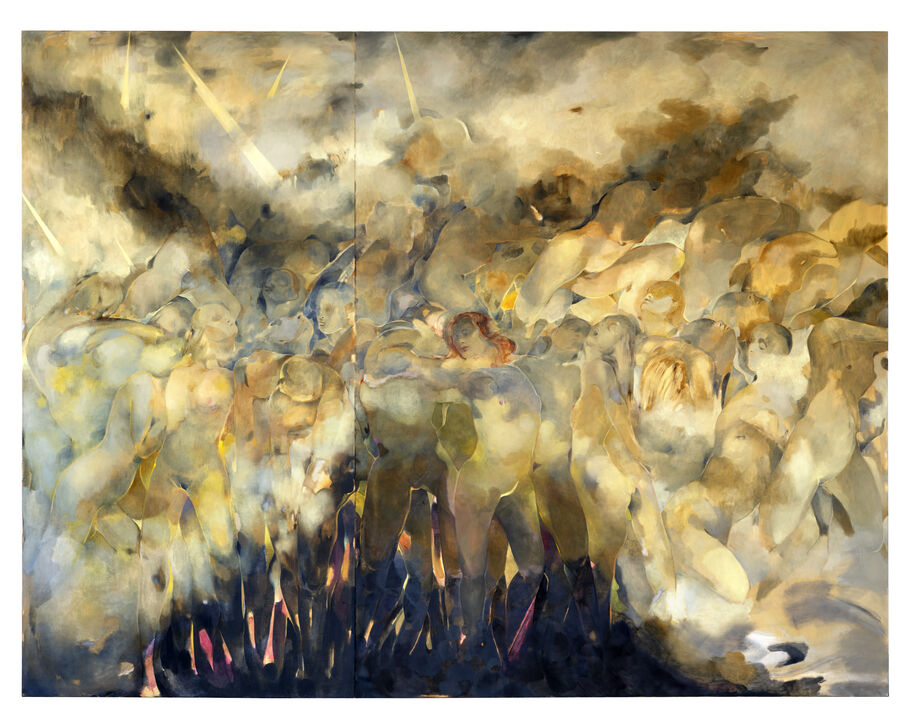

Eva Helene Pade, Skygge over mængden (Shadow above the crowd), 2025. © Eva Helene Pade. Photo by Pierre Tanguy. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

The more Pade contemplated that smoke, the more it seemed to encapsulate the murky state of current events today, where social media conspiracy theories, real corruption, and concurrent crises foster a societal state of exhausted bewilderment. “Everything is confusing and ambiguous,” Pade explained. By foregoing linear narrative in “Søgelys,” she said, “You stay in that confusion and violence a bit more.”

The show’s first—and largest—work, Skygge over mængden (Shadow above the crowd) (2025), features a flaxen haze enveloping a cresting horde of nudes, its weightless shadows resolving into the shape of a hulking airplane as the viewer backs away. That haze settles upon the following frenzied dance floors featuring throngs of figures tangling and tangoing, challenging the boundary between the individual and the collective.

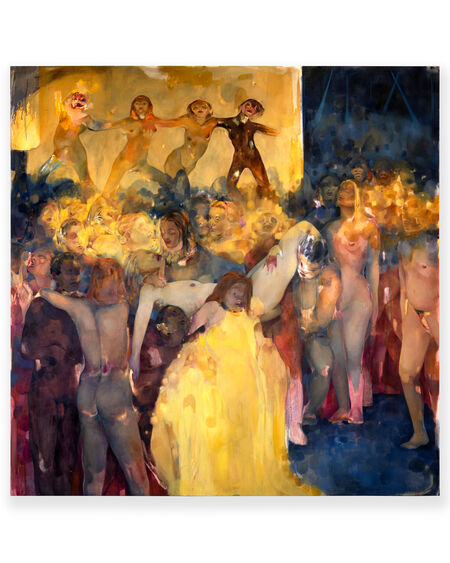

Eva Helene Pade, Den Fundne (The found one), 2025. © Eva Helene Pade. Photo by Pierre Tanguy. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

Eva Helene Pade, Midt fald (Mid fall), 2025. © Eva Helene Pade. Photo by Pierre Tanguy. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

Archetypes reappear across canvases, transforming “Søgelys” into one ensemble, rather than a series of discrete works. Across its varied scales, this show presents perhaps Pade’s most high-contrast work to date. Only the larger paintings, however, allow her to play with light in such a way that it deceives the viewer. In Den fundne (The found one) (2025), for instance, the viewer’s gaze is initially directed towards the dancers onstage, rather than the real focal point, the comparatively drab reveler collapsed in the crowd, like a Renaissance pietà.

There’s always more going on in a scene than meets the eye. Maybe painting isn’t so impotent after all: For starters, it can teach us how to look, and look again.

VB

Vittoria Benzine

Vittoria Benzine is a Brooklyn-based essayist, journalist, clairvoyant, and road tripper covering contemporary art with a focus on social practice, counterculture, and chaos magic. She writes a psychic column for Elephant Magazine, and contributes to a wide range of publications, including Artnet News, Maxim, Interview, and Artsy.