Some Thoughts on the Labor Market

Ordinarily, we would have received the Bureau of Labor Statistics report on the Employment Situation the morning of October 3. Expectations from analysts settled at 51,000 jobs added in September, compared to 22,000 in August. Stronger payroll growth would be a boost for the Trump Administration amid weak economic indicators. Weaker or negative payroll growth would further stoke fears of an impending recession. We would now be looking forward to the Federal Reserve’s federal funds rate decision at the end of the month and the next Jobs Day in early November.

However, the ongoing government shutdown will delay the release of labor market data until a funding agreement is reached, so we need to make our best judgments of the state of the labor market without new official data to guide us. Private sector data has tried to fill the gap, and most show a labor market that is stalling or weakening.

I will not try to guess what this month’s report would have said. Instead, I will offer some observations on what we know about the state of the labor market as of the last BLS report.

The super-tight labor markets of the pandemic period are definitely over.

The post-pandemic economy was characterized by a tight labor market, which was very favorable to lower-wage and less privileged workers. Overshadowed by inflation, the very favorable conditions for workers aren’t a central part of our narrative of the economy during those years, instead showing up in the negative form of employers’ complaints.

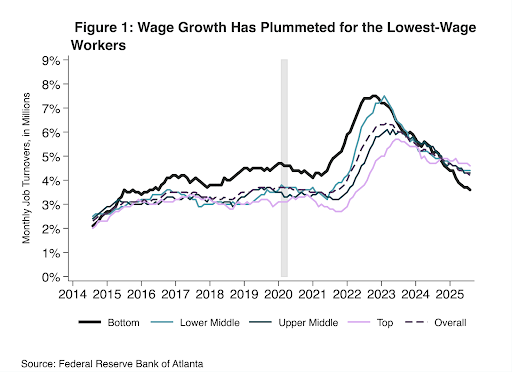

But what looks like a labor shortage from one side looks like an abundance of jobs from the other. As Arin Dube and his coauthors pointed out in an important paper, the three years after 2020 reversed a full quarter of the rise in wage inequality of the previous four decades.

Yet this period was hardly perceived as an economic success story. The obvious reason is inflation: while wages did rise faster than prices at the bottom of the distribution, most of the compression described by Dube and his colleagues took the form of wages higher up the income scale falling in real terms.

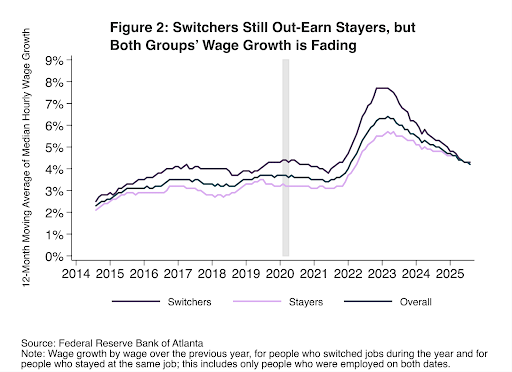

Another way to reconcile the big relative gains for those lower down the distribution, with the very negative perceptions of the economy: The combination of tight labor markets and rising prices was good specifically for people who sell their labor on a free market. It was bad for people who enjoy the protections of professional credentials, unions, public employment or other sources of stable employment conditions: In this case, protection from the short-term vagaries of the labor market was a negative. It’s worth noting in this context that almost all the outsized wage gains of the post-pandemic period went to people who switched jobs; it’s easier to jump ship for a better offer if you are a janitor or roofer or cashier than if you are a teacher or lawyer.

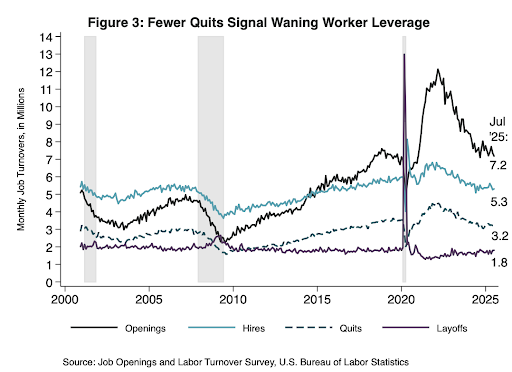

That period is over now. The great compression of wage income ended in late 2023. Over the past two years, low-wage workers have lost ground relative to other wage-earners. The great reshuffling has ended too: quits, new hires and job openings are all back down to pre-pandemic levels. This is still a reasonably strong labor market, but it is not a historically tight one, as it was a couple of years ago. Despite the stable headline unemployment rate over the past year, it is clear that the bargaining position of workers relative to employers is substantially worse than it was a year or two ago. There was a period when Jerome Powell would mention, at every press conference, the need to “rebalance” a labor market that was tilted too far in favor of workers, and against employers. He’s not using that language now, instead worrying about the “downside risks to employment.”

Quits, in particular, are a strong indicator of workers’ bargaining power. People’s willingness to leave their current job is a vote of confidence in their ability to find another one, and the threat of quitting is the main practical leverage that most workers have over their boss. The historically high rate of quits over 2021-2023 was an important sign of a labor market unusually friendly to workers; its subsequent decline suggests one that no longer is.

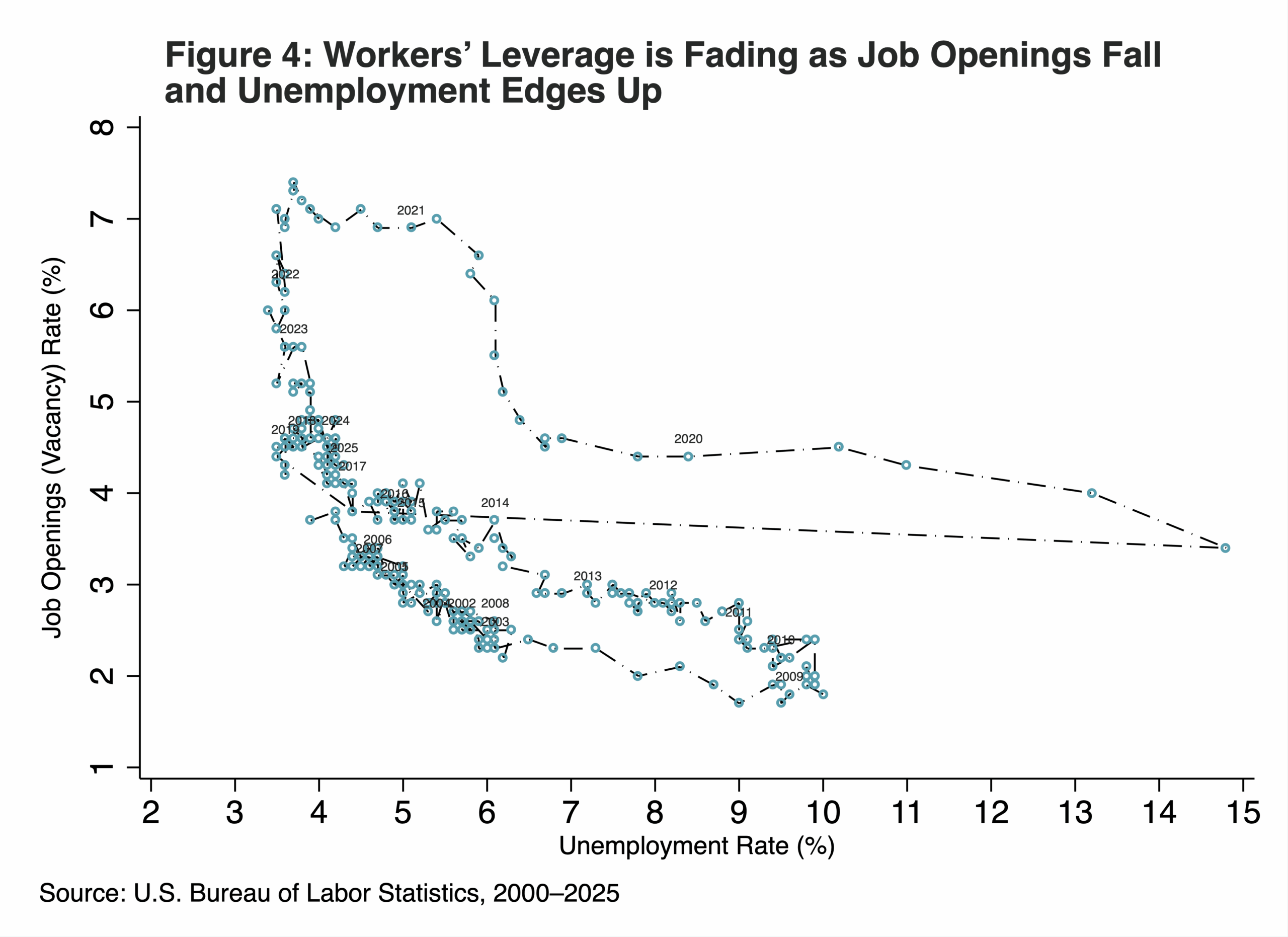

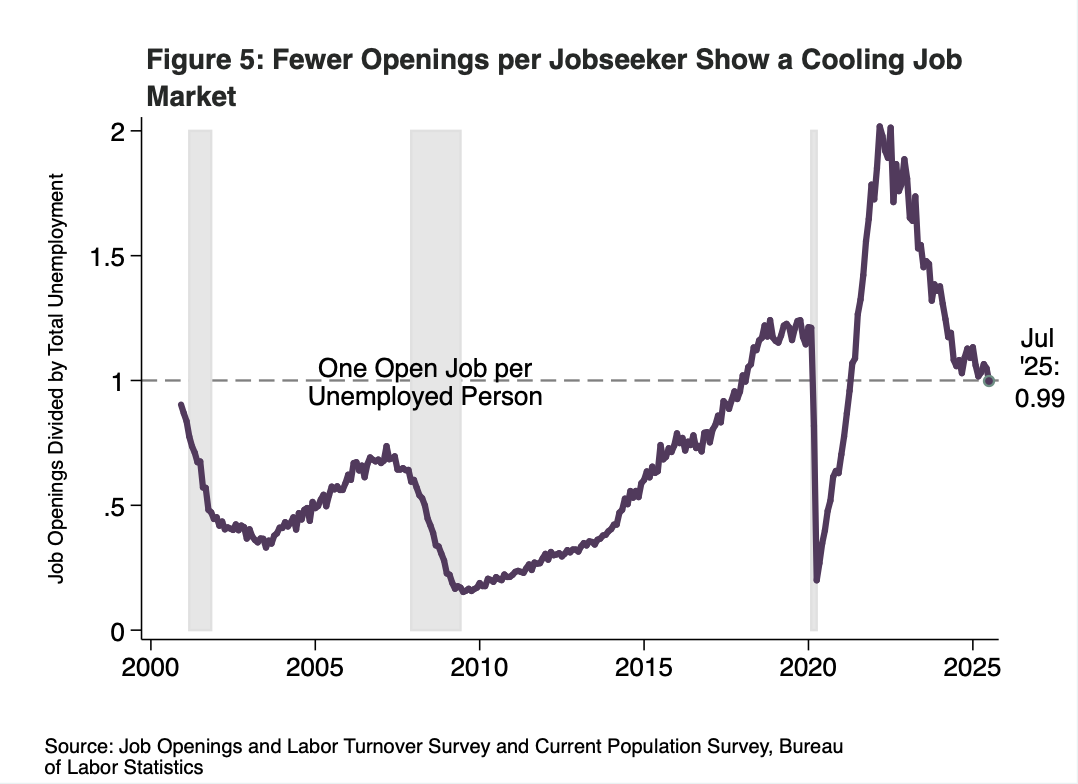

One way of thinking about the balance of bargaining power in the labor market is the Beveridge curve, which compares the share of jobs vacant with the share of workers unemployed. The figure nearby shows this metric for the US for the past 25 years. Points in the upper left correspond to a tight labor market – few unemployed workers and lots of unfilled positions, meaning workers have relatively more leverage. Points in the lower right are the opposite – lots of unemployed workers and few unfilled jobs, so that prospective employers can pick and choose and workers have to take what they can get. Points higher up on the right correspond to what’s known as structural unemployment – lots of people want to work, and there are businesses that want to hire, but for some reason they can’t connect with each other.

Job openings have been drifting down steadily, and unemployment has been creeping up. A couple of months ago, openings per unemployed person fell below one. There are questions about how reliable the vacancy measure is, especially when comparing over widely-separated periods; but by this metric, it’s a worse market for jobseekers not just than the exceptional recovery from the pandemic, but than the last couple pre-pandemic years as well.

In the absence of some major change, it’s hard to imagine a return to the rapid wage growth at the bottom of a few years ago. 2021 and 2022 were very good years for young people entering the job market; 2026 will not be.

The job market is stronger than one would expect given slowing demand and weak growth in employment.

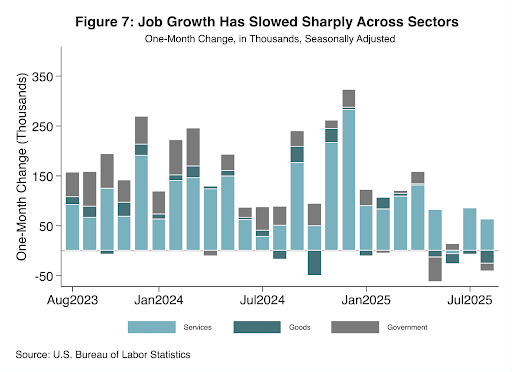

In some ways, the puzzle about the job market is not that it has gotten weaker, but that it is still as strong as it is. The big headline in last month’s jobs report was weak employment growth and a downward revision to employment numbers from earlier this year. Employment was up a bit less than 1.5 million over the year ending in August, not just slower than the post-pandemic recovery, but well below the consistent two million jobs per year that were being added prior to the pandemic.

The Financial Times summed up the situation well:

American industries most exposed to trade turmoil have slammed the brakes on hiring and in many cases begun to lay off workers, causing growth in the US labour market to grind to a halt.

It’s worth pausing over this sentence for a moment, to call attention to something that should be obvious, but is not always foregrounded: Hiring decisions are made by employers. Businesses choose a level of output based on current or anticipated demand for their products. To explain why the employment numbers are what they are, we need to think about demand for current output, and perhaps business expectations about future demand. Labor supply explains nothing about why employment is growing so slowly today, or why it was growing more rapidly last year.

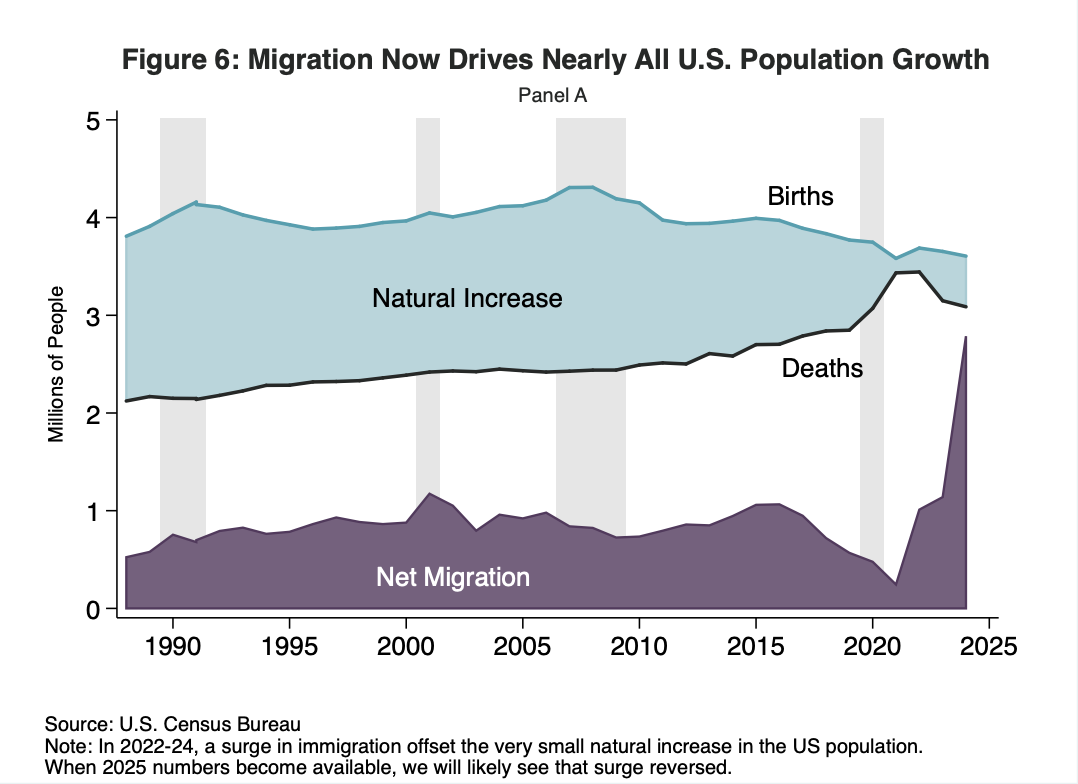

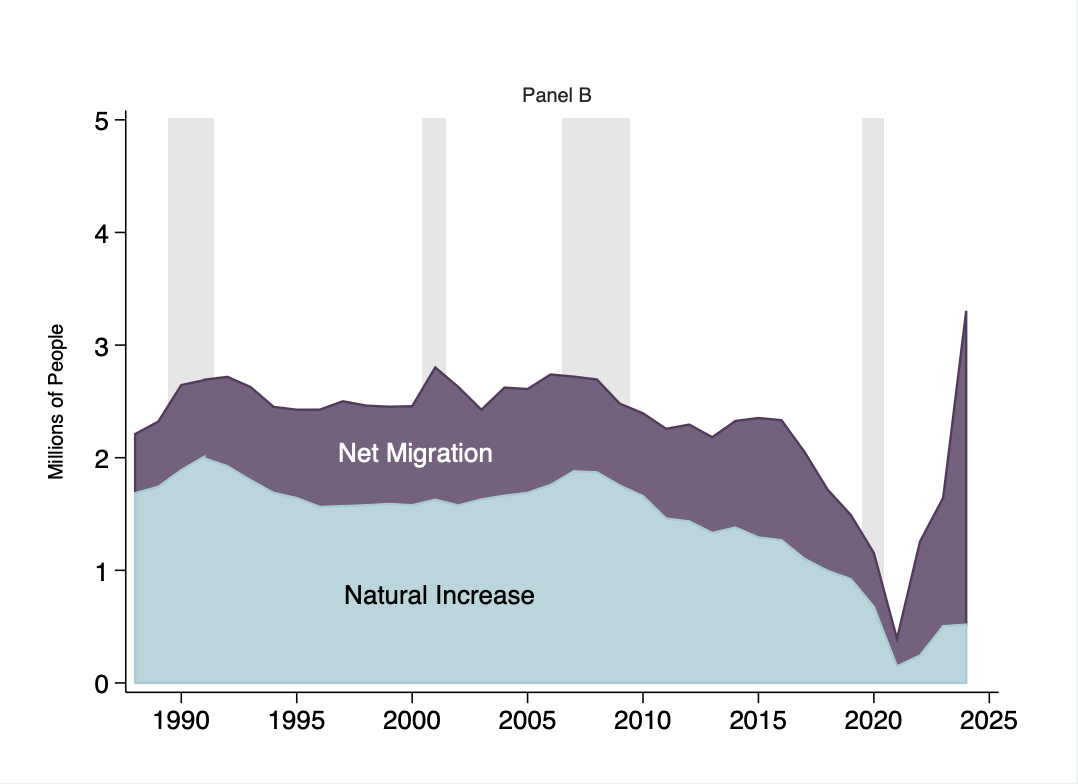

At the same time, it is true that the working-age population is now growing more slowly than it was a year or two ago. Last year probably saw the greatest number of immigrants, in absolute numbers, in U.S. history. This meant that the labor force was growing rapidly, despite the much slower natural increase in the US population since the Great Recession. Much lower immigration this year, along with the secular fall in natural growth, means the working-age population is probably growing quite a bit slower now; but because of the way the BLS constructs its population estimates, this will not show up in the official data until next January. Again, slower population growth has no direct effect on actual employment, which depends strictly on the demand side. But it does mean that slower employment growth implies a tighter labor market than it otherwise would.

Over the year ending in August, total employment in the US grew by just 0.9 percent. In the past 70 years, the United States has never seen employment growth that slow outside of a recession. The latest ADP report – which, in the absence of official data, is perhaps our best source of employment data – suggests that only 32,000 new jobs were created in September, implying that employment growth may be dropping further into recession territory.

Yet the labor market, while weaker than a couple of years ago, looks nothing like a recession. After rising a bit from late 2023 to early 2024, the headline unemployment rate has been basically stable for the past year and half. The fraction of working-age people employed has also been essentially constant. This is a surprisingly rare development – historically, the employment rate shows few extended periods of stability, but rather rises steadily in expansions and falls during recessions.

The unusual combination of slow employment growth and continuing labor market strength presumably reflects the combination of weaker demand for labor, and a shrinking (or at least more slowly growing) pool of available workers. The “curious balance” (in Powell’s words) between these two trends is why unemployment has held steady despite what now seems to have been a very sharp fall in employment growth over the past year. Weak employment growth leads to less slack in the labor market if the potential workforce is also growing more slowly.

There is no reason to think that the immigration crackdown has benefited native-born workers.

Does this mean, as Trump Administration officials have claimed, that anti-immigrant policies are working, at least as far as the labor market is concerned? No, it does not.

For a given level of demand, a smaller labor force does mean a more favorable market for workers. But the condition “for a given level of demand” is key. If immigration is sharply down from 2024 levels, that means fewer people available for jobs. But it also means less spending. So while lower immigration may help explain why unemployment has held steady despite much slower hiring, that does not mean that unemployment would be higher in a world where 2024 levels of immigration had continued. In that hypothetical world, businesses would be selling more and hiring would be stronger.

One thing we can say for sure: there is no reason to think that the immigration crackdown has disproportionately benefited native-born workers. There has not been a surge in employment among the US born, despite claims to the contrary from the Trump Administration. In an excellent post, Jed Kolko walks through the data on this, and explains the source of the confusion. The BLS surveys households, but updates the total population only once a year, based on the census; in between it uses projections from the previous census. So if fewer people answering BLS questionnaires say they were born abroad — either because there really are fewer immigrants, or because immigrants are more wary of speaking to government officials — then, mechanically, the BLS must assume a greater native-born population. As Kolko convincingly shows, this statistical artifact explains the entire apparent surge in native employment.

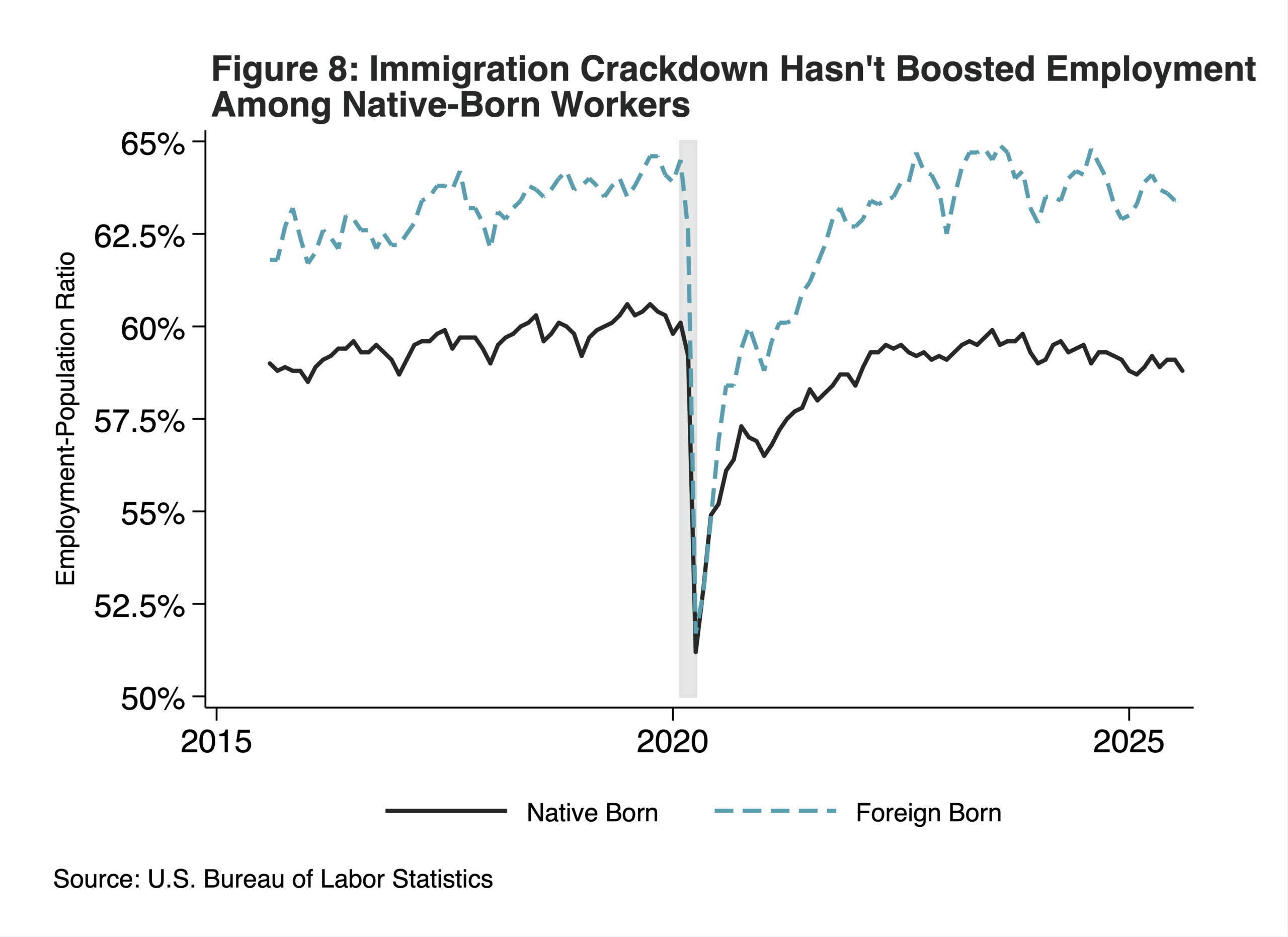

We can see this clearly if we break out employment rates by native- and foreign-born. The employment rate for the native-born population peaked in mid-2023 and has been declining steadily over the past two years; there is no change in this trend since this year, despite the crackdown on immigrant workers.

Whatever is going on in the labor market, “native workers are benefiting from reduced competition from immigrants” isn’t it.

So what is happening? I think the story is fairly clear. Trump’s volatile trade policy has frozen impacted businesses in place. This is backed up by qualitative surveys of businesses conducted by regional Federal Reserve Banks, as well as public earnings calls. Businesses are not laying off large numbers of workers, but they aren’t hiring, either. Workers also have less ability to bargain for higher wages and fewer opportunities to switch jobs. A reduction in the labor supply through reduced immigration has lowered the “breakeven” point for job growth, but labor demand appears weaker nonetheless. Everyone is stuck, and it doesn’t appear that a breakthrough is coming anytime soon.