In October 2024, the aurora borealis lit up Earth. Astronaut Don Pettit captured it from the ISS, while Babak Tafreshi captured it in Massachusetts.

In October 2024, the aurora borealis lit up Earth. Astronaut Don Pettit captured it from the ISS, while Babak Tafreshi captured it in Massachusetts.

Photography is all a matter of perspective: one angle is visually uninteresting and doesn’t tell a story, but another viewpoint of the same subject is alive with emotion and meaning.

Few perspectives are more distinct than viewing Earth from 250 miles (400 kilometers) above versus standing upon its surface, and this is precisely what astronaut Don Pettit and Nat Geo photographer Babak Tafreshi did recently for a spectacular project called From Above & Below.

“Sometimes you look at a landscape on Earth from space, it looks flat and boring,” Tafreshi tells PetaPixel. “And then from the ground it’s a stunning scenery of otherworldly landmarks.”

Tafreshi cites Madagascar as an example. “From space, it is completely dark and flat with no artificial light,” he says. “But from the Earth, from the ground, it’s one of the most striking landscapes anywhere on the planet.”

Two very different perspectives of Madagascar: Pettit captured it 250 miles above, while Tafreshi photographed Madagascar’s famed baobab trees against a backdrop of swirling star trails that converge around the celestial South Pole. | Photo by Don Pettit

Two very different perspectives of Madagascar: Pettit captured it 250 miles above, while Tafreshi photographed Madagascar’s famed baobab trees against a backdrop of swirling star trails that converge around the celestial South Pole. | Photo by Don Pettit  Photo by Babak Tafreshi

Photo by Babak Tafreshi

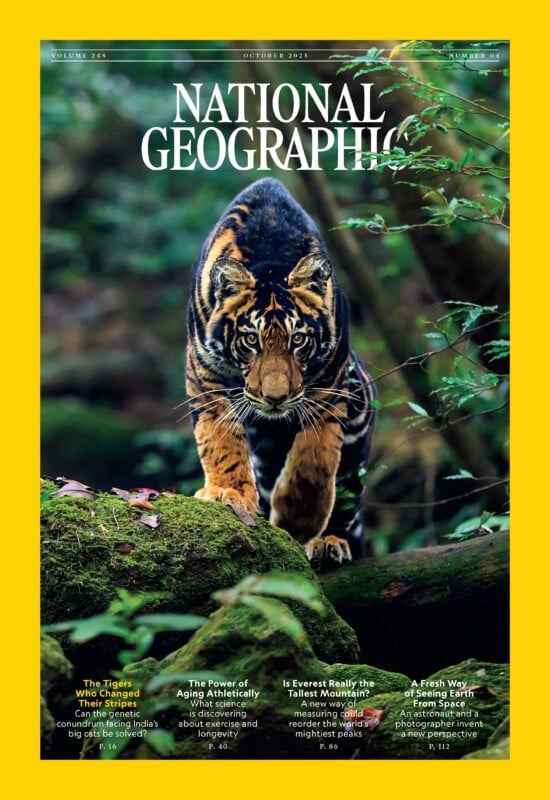

From Above & Below is featured in the October edition of National Geographic where there are 22 photos printed. Tafreshi and Pettit kept in touch via WhatsApp and email while Pettit was on his most recent space mission where he lived onboard the International Space Station (ISS) for 220 days.

Astronauts onboard the ISS keep a busy schedule, so Pettit had to find time for the project in between his duties. But the pair were able to capture the same events happening at the exact same time from space and Earth.

On October 10, 2204, a strong geomagnetic storm lit up the Northern Hemisphere with colorful auroras. Pettit rushed to one of the ISS’s windows to document the vibrant curls of green and pink light before they vanished. Fortunately, Tafreshi didn’t have to travel far. He captures the same swirling pink phenomenon above his neighborhood in Salem, Massachusetts. | Photo by Babak Tafreshi

On October 10, 2204, a strong geomagnetic storm lit up the Northern Hemisphere with colorful auroras. Pettit rushed to one of the ISS’s windows to document the vibrant curls of green and pink light before they vanished. Fortunately, Tafreshi didn’t have to travel far. He captures the same swirling pink phenomenon above his neighborhood in Salem, Massachusetts. | Photo by Babak Tafreshi

For example, when a strong geomagnetic storm created a dazzling aurora display across North America in October 2024, Tafreshi was able to go outside his front door and take a picture of the same phenomenon that Pettit was photographing in space. When Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) passed some 44 million miles from Earth, Pettit was able to capture it from the ISS while Tafreshi traveled to Puerto Rico.

Both photographers captured the A3 comet as it made its once every 80,000-year appearance in the solar system, September 2024. | Photo by Don Pettit

Both photographers captured the A3 comet as it made its once every 80,000-year appearance in the solar system, September 2024. | Photo by Don Pettit  Photo by Babak Tafreshi

Photo by Babak Tafreshi

Tafreshi calls the comet and aurora photos the “most synchronous”, but the purpose of the project was to contrast perspectives. For example, Tafreshi went to the Manicouagan Reservoir, which was formed when an asteroid slammed into Canada 214 million years ago. Known as the Eye of Quebec, its markings — captured by Pettit — are distinct from space, but from terra firma, it looks like a peaceful lake and the overall eye structure is hidden.

The Eye of Quebec, or the Manicouagan Reservoir, looks very different from above and below. | Photo by Don Pettit

The Eye of Quebec, or the Manicouagan Reservoir, looks very different from above and below. | Photo by Don Pettit  Photo by Babak Tafreshi

Photo by Babak Tafreshi

The photos seen here and in National Geographic magazine represent a tiny fraction of the project. From Above & Below has been in the works since 2012, and Tafreshi sometimes had to make last-minute travel plans to get to a location that Pettit was going to be flying over.

“You can make long-term forecasts about the space station’s orbit, but because there are adjustments by boosters and there are orbital adjustments, it changes after a few days,” Tafreshi explains. “So you cannot really rely on long-term forecasts that the space station is definitely going to fly [over a specific location].”

It means that it is “almost impossible” for the two photographers to capture a landscape at the exact same time. Some of the photos are days apart, but Tafreshi has spent hours trawling through the photos Pettit took in space.

“When I decided to make this project in 2012, I looked at the expedition images, and it was roughly about 10 to 20,000 images per expedition,” Tafreshi explains. But for Pettit’s latest expedition, he took roughly one million photos.

“With the new cameras like Nikon Z9, they are using it in burst mode… So I never imagined that he’s going to create one million images, and I’m responsible for going through his one million images, because you need to find the archival pairs. And that was the aim of the project, not only synchronous but also archive.”

It means that as Tafreshi is going through Pettit’s photos, he is cross-checking them with his own, charting the flightpath of the ISS to see if he took a photo in the same area while Pettit was above. Don’t forget, the ISS orbits the globe every 90 minutes, taking in countless sunrises and sunsets.

Tafreshi’s and Pettit’s photos are featured in this month’s edition of National Geographic.

Tafreshi’s and Pettit’s photos are featured in this month’s edition of National Geographic.

The pair hope to make a book from their joint endeavor. “Now we are in this hype that we need to go to Mars, we need to go to the Moon, we need to explore every other planet, and we forget about our own planet,” Tafreshi says.

“I hope this project brings back a very important message that although there is a huge, beautiful universe to explore, the Universe tells us a very direct message: life is unique on Earth.”

“We have not found any other planet with life, and we have not found any other planet that is so hospitable,” he continues.

“By looking at the space, you understand the value of life on Earth, and you understand the purpose of human beings on this planet… And this message is within our photography as well. You look above to space and you look back to Earth and you’ve found how important this little pale blue dot is.”

For more on this story, visit Nat Geo.

Image credits: Photographs by Don Pettit and Babak Tafreshi. Courtesy of Nat Geo.