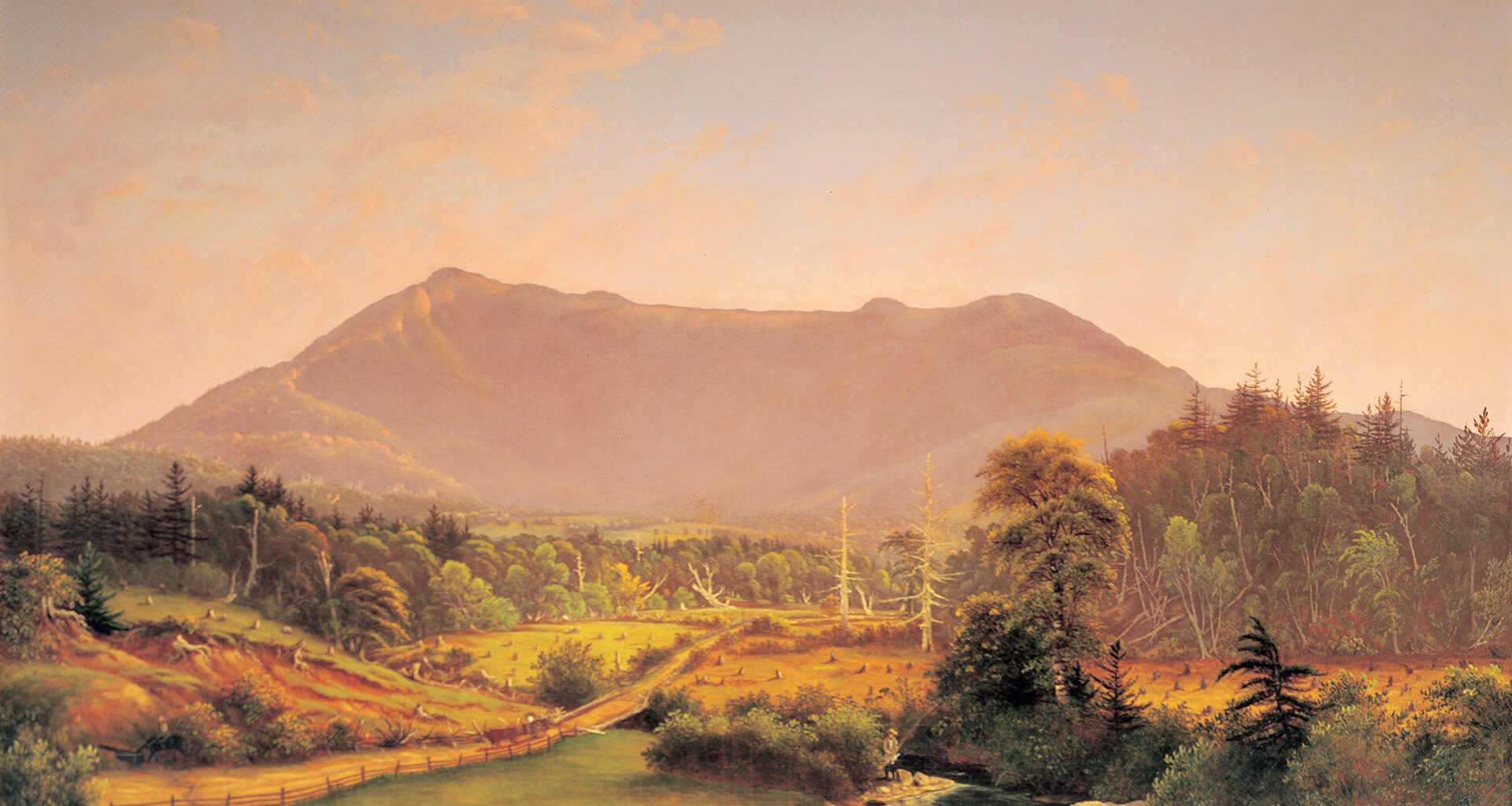

Mount Mansfield was one of Charles Heyde’s favorite subjects, featuring in many of his paintings. This work, dated circa 1857, is currently on display at the Fleming Museum. Image via Fleming Museum of Art

Mount Mansfield was one of Charles Heyde’s favorite subjects, featuring in many of his paintings. This work, dated circa 1857, is currently on display at the Fleming Museum. Image via Fleming Museum of Art

The visit was almost more than artist Charles Heyde could have hoped for. One day in the early 1850s, Heyde was called upon at his Brooklyn painting studio by a pair of poets, one in his early 30s, the other in his mid-50s. Heyde must have been particularly excited to meet the older man, William Cullen Bryant.

Though little remembered today, Bryant wrote widely popular poems in which nature often served as a metaphor for spiritual truth. His activism on a range of issues — from opposing slavery to supporting the creation of a large, central park in Manhattan — made him a leading cultural figure in New York City and the nation.

For a young artist like Heyde (pronounced Hi-dee), the fact that Bryant would take the time to visit his studio, admire his landscape paintings and talk with him, must have felt like a benediction. Perhaps this connection with Bryant was a sign that he too had what it took to be a great artist.

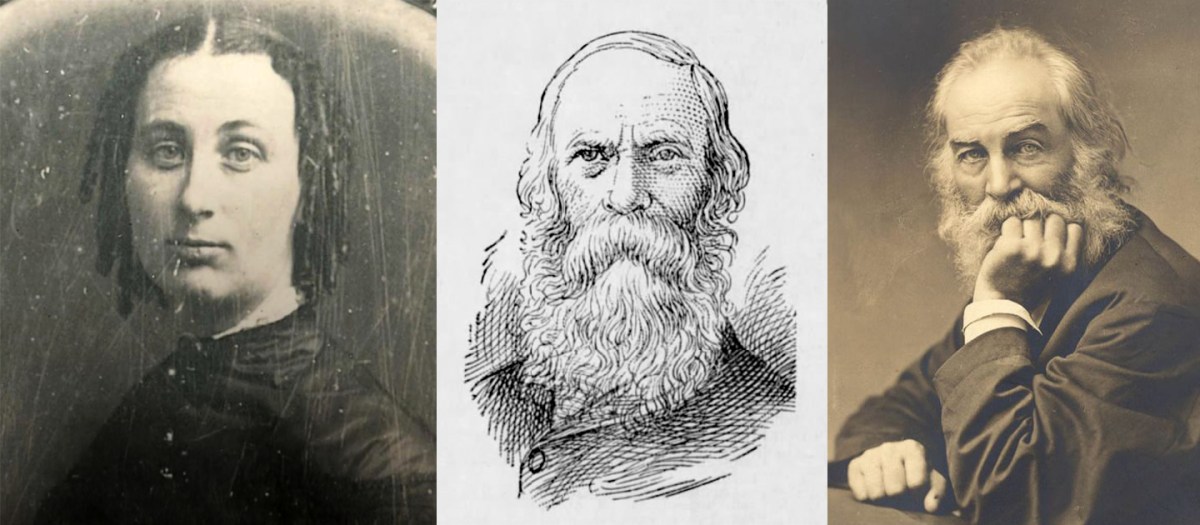

Walt Whitman, right, introduced Charles Heyde to his sister, Hannah, at the Whitman family home in Brooklyn. Charles courted Hannah and the couple soon married and moved to Vermont. Whitman later regretted introducing Heyde to his sister when it became evident that he was abusive to Hannah. Hannah and Walt Whitman photos via the Walt Whitman Archive, etching of Heyde via Newspapers.com

Walt Whitman, right, introduced Charles Heyde to his sister, Hannah, at the Whitman family home in Brooklyn. Charles courted Hannah and the couple soon married and moved to Vermont. Whitman later regretted introducing Heyde to his sister when it became evident that he was abusive to Hannah. Hannah and Walt Whitman photos via the Walt Whitman Archive, etching of Heyde via Newspapers.com

Heyde might have believed this meeting with Bryant would change his life, but it was his connection with the younger poet that proved far more significant. That man’s name was Walt Whitman. Though a virtual unknown at the time, Whitman had recently begun writing some of the poems he would include in “Leaves of Grass,” the poetry collection that would make him a household name.

Walt liked Heyde enough that he invited him to visit the Whitman homestead. There Heyde met and soon wooed Whitman’s favorite sister, Hannah. The couple married in March 1852. That same year, Charles and Hannah traveled north to Vermont, taking the train to North Dorset.

Like other members of the so-called Hudson River School of landscape painters, Heyde was looking for inspiring views. Named after one of their favorite subjects, the Hudson River School painters were a group of artists who, from roughly 1825 to 1875, strove to depict the natural beauty of their young country. In addition to the Hudson River Valley, many painters made regular pilgrimages to the White Mountains of New Hampshire.

Perhaps seeking something off the artists’ beaten path, Heyde chose Vermont. He would make the state his principal subject, and soon his home, for the final four decades of his life. In the process, he became one of Vermont’s most prominent landscape painters of the 19th century, along with James Hope of Castleton.

In a letter, Heyde wrote rapturously of the scenery: “Nothing can exceed the wild, bold, natural beauty of this place at present. The hues are incomparable and the artist who in his studio imagines himself a creator or interpreter of nature and her glorious beauties, he finds himself humbled … a child in power, only possessing wonder, admiration and the conviction of his weakness.”

For the next four years, the Heydes divided their time between Brooklyn and Vermont. Visiting Dorset, Rutland, Arlington and Bellows Falls, Charles painted scenes along the Connecticut River, Saxtons River, the Batten Kill and the Black River. During that time, the Heydes moved from boardinghouse to boardinghouse. While Charles found the work stimulating, Hannah wrote home that she felt lonely and found it difficult to form friendships because of their transient lifestyle.

In 1856, he and Hannah moved to Vermont permanently. They picked the bustling port community of Burlington, an area ripe with scenery that Heyde would paint again and again — the peaks of Mount Mansfield and Camel’s Hump, as well as Lake Champlain backed by the distant Adirondacks.

Burlington’s comparatively small population posed a challenge for an artist trying to earn a living. While most Hudson River School painters lived in New York, Boston or Philadelphia, Heyde had chosen a town whose population was less than 8,000 when he and Hannah arrived. The population would peak at about 14,000 during their time there, but that was still a small pool of potential buyers.

Heyde was enterprising, selling paintings directly from his studio and arranging to exhibit his work in downtown storefront windows and hotel lobbies, where they might catch the eye of travelers.

Greenville Benedict, editor of the Burlington Daily Free Press, quickly became an admirer and frequently mentioned Heyde’s paintings in his paper. A typical article from 1858, headlined “A Fine Painting,” informed “Lovers of art and Vermont scenery” that a Heyde landscape could be viewed at James Brinsmaid’s store on Church Street, but warned that it would only be on display for 10 days. Such notices helped attract Heyde’s main collectors, middle- and upper-class Burlingtonians who wished to show hometown pride in how they decorated their homes.

Heyde soon established a studio at the corner of Maple Street and Water (now Battery) Street, in the Rutland and Burlington Railroad depot. The location was extremely convenient for his painting forays. In preparing for a 2001 retrospective of the artist’s work at the University of Vermont’s Fleming Museum, exhibit co-curator Thomas Pierce scouted nearby locations from which Heyde had painted. He found that many of the spots were near the train tracks, leading Pierce to theorize that Heyde took advantage of the rail lines that were fast expanding in his era.

In his research, Pierce noted how Heyde must have visited the locations many times. Over the years the painter’s canvases recorded changes to the landscape. Early views of Mount Mansfield from across Browns River in Jericho, which would become a classic Heyde composition, show a line of trees along the water. In later canvases, the trees are gone — possibly the result of flooding, Pierce suggests — and a barn, missing in the early pieces, appears in the midground. In that way, surveying Heyde’s works can feel like watching a time-lapse film of Vermont’s development during the second half of the 19th century.

Unlike many Hudson River School painters, Heyde didn’t erase all evidence of human habitation. His paintings often show signs of expanding settlement, including tree stumps and dirt roads leading into the wilderness, as well as technological advancements: trains dwarfed by the serene scenery and steamboats set upon a luminous Lake Champlain. His paintings suggest he believed that in Vermont modern innovations and awe-inspiring nature were compatible.

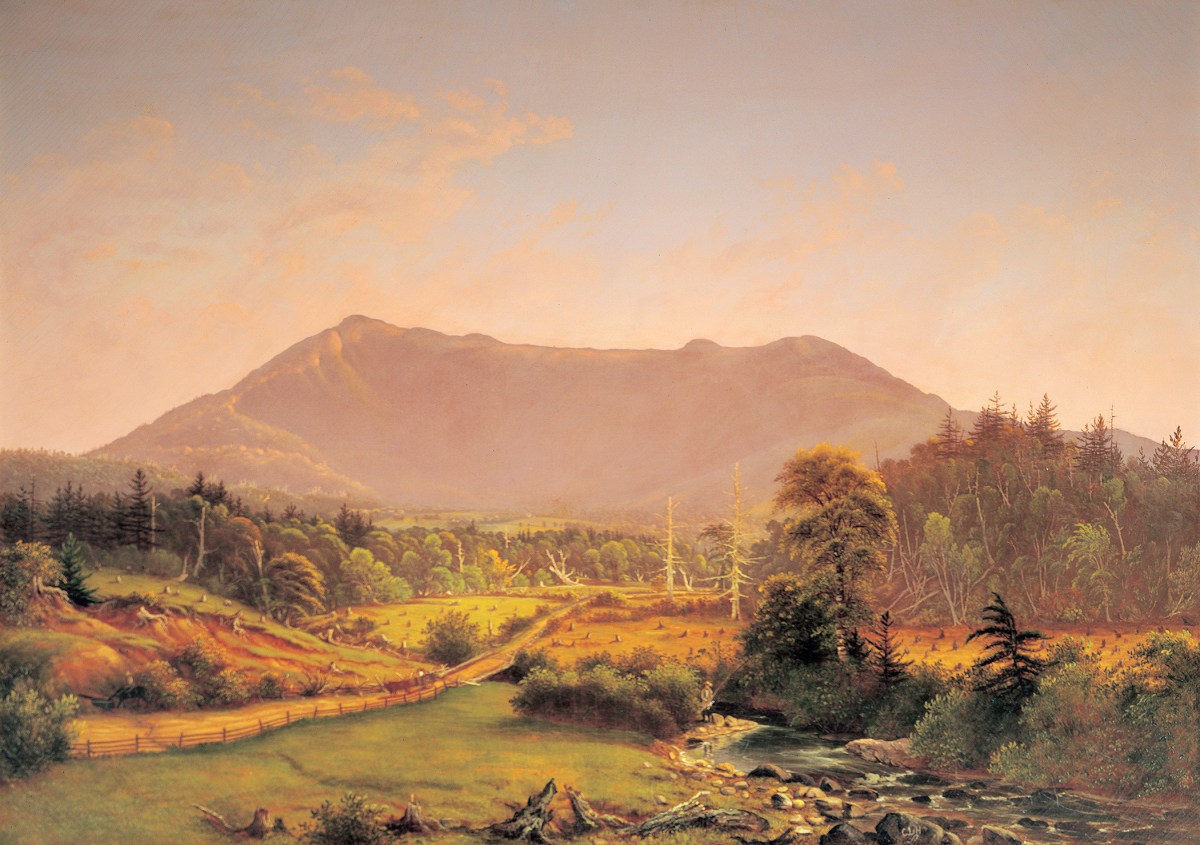

Charles Heyde didn’t shy away from depicting signs of human impacts on nature, like these tree stumps in a cleared field in “Shelburne Point at Sunset,” painted circa 1857. Contributed

Charles Heyde didn’t shy away from depicting signs of human impacts on nature, like these tree stumps in a cleared field in “Shelburne Point at Sunset,” painted circa 1857. Contributed

Heyde’s paintings still resonate today. As William Lipke, a UVM art professor noted in a 2001 essay, many of the views Heyde chose to depict are relatively unchanged today and are “‘places of delight’ that identify the unique topographical and scenic features of the Champlain Valley.”

In 1862, Heyde won a prestigious commission from the Vermont Legislature to redesign the state coat of arms. Heyde’s version included symbols from the previous coat of arms: a pine tree, sheaves of wheat and a cow. These he set against a backdrop of mountains clearly identifiable as Camel’s Hump and Mount Mansfield.

The Heydes finally found a permanent home in 1864 when they purchased a brick house at 21 Pearl Street, right next to Battery Park, which has a spectacular view of Lake Champlain and the distant Adirondacks.

The tranquil landscapes Heyde depicted contrasted sharply with life at home. In fact, the Heydes’ marriage was an increasingly rocky one. Hannah wrote regularly to her mother and siblings of her husband’s abusive behavior. “He does not hurt me much when he gets angry,” she had written her mother in 1856, “he threatened to choke me to death(,) he has struck or pushed me about some, once he bit me a little on the shoulder(,) more to hurt(,) tore or ripped the sleeves of my dress that I wore but all that I care nothing at all about, if he would not talk so to me.”

It would have been easier for Hannah if her husband also treated other people this way but, she wrote, “he can leave my room with the most horrid mouth and be as pleasant as any one you ever saw to any one he meets.”

The Whitmans would sometimes mail Hannah books, or money when the Heydes ran into financial trouble, which she said “Charlie,” as she called her husband, would sometimes take. Heyde made a habit of reading the letters Hannah exchanged with her family.

For his part, Heyde complained about Hannah, or “Han,” as he referred to her, in letters to her family. Writing to Mrs. Whitman and to Walt, who he addressed as “Brother Walter,” Heyde called Hannah lazy and neglectful of her housework; said she often took to her bed, saying she was ill; claimed she would noisily interrupt him in his home studio and rifle through his things; and was suspicious when he returned from outings, sniffing his coat, gloves and handkerchief, accusing him of having an affair.

The Whitmans fully supported Hannah and helped her the best they could. But they lacked the financial resources to extract her from her apparently abusive marriage. If Hannah wanted to leave Charles, she would have found it challenging; married women had few legal rights. Walt Whitman clearly regretted introducing his sister to this man who he now called “a damned lazy scoundrel.”

Meanwhile during this time, Heyde faced a serious professional challenge. The new field of photography was muscling in on the turf that had been painters’ sole domain.

“Because he was up against photography as competition he had to keep his paintings at a price that was affordable,” explained Pierce. As a result, critics say that Heyde’s later works don’t measure up to his earlier ones. “He couldn’t spend a week doing a painting anymore,” Pierce said, “he had to spend two days, because the more you work it, the more expensive it becomes.”

Some also claim that Heyde’s work started to suffer because he was drinking too much and showing signs of dementia. Pierce thinks that’s not accurate. He pointed to a set of four paintings that recently came up for auction. They are fine examples of the artist’s skill, even though they were painted in the 1880s, late in his career. Heyde hadn’t lost his touch, said Pierce, who suspects the paintings were well-paid commissions, so he didn’t have to rush them.

READ MORE

The only known surviving portrait of Heyde is an etching that appeared as part of a newspaper advertisement for a patent medicine in spring 1892. In the ad, Heyde and a half dozen other prominent Vermonters offered testimonials about the virtues of Paine’s Celery Compound, which had been devised by Windsor druggist Milton K. Paine and was manufactured and sold nationally by a Burlington company. The product claimed to cure a variety of ills, including neuralgia, dyspepsia, constipation and biliousness, as well as liver and kidney ailments.

“I avail myself of the privilege of thanking you — sincerely — for the refreshing sleep I have enjoyed through the efficacy of Paine’s Celery Compound,” Heyde said in the ad.

(The product’s ingredients included celery and coriander seed, orange and lemon peel, hydrochloric acid, glycerin and simple syrup. An analysis of the compound after passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906 revealed that it was also about 20% alcohol.)

Heyde was diagnosed with chronic dementia and admitted to the Vermont State Asylum in Waterbury, where he died on Nov. 3, 1892. He is buried a short distance from the home he shared with Hannah, in Burlington’s Lakeview Cemetery.

Hannah remained in their Pearl Street home for the rest of her life. After she died in 1908, her body was transported back to Brooklyn for burial. The Heydes’ home stood until 1968, when it was demolished as part of an urban renewal project. St. Paul’s Cathedral now stands at the site.

Of course, artists’ work outlives them.

Like many Charles Heyde paintings, “Lake Champlain and Rock Point,” painted in 1858, is owned by a Burlington-area family. Contributed

Like many Charles Heyde paintings, “Lake Champlain and Rock Point,” painted in 1858, is owned by a Burlington-area family. Contributed

The Fleming Museum staged its first Heyde retrospective in 1965, three-quarters of a century after the artist’s death. At the time, 80 paintings were known to exist. For the 2001 show, Pierce and his co-curator Eleazer Durfee tracked down another 74 paintings. Although they found Heyde paintings as far away as Alaska, most had never left the area. They had been passed down through families. Some hung over fireplaces, while a few had been stored and forgotten in attics.

In the quarter century since that show, Pierce received numerous tips about other Heydes held in private collections or being offered for sale. Pierce meticulously logs each newly discovered piece in a digital catalogue he created. By his count, Heydes’ known surviving works now number 226.

Among the more unusual paintings Pierce has discovered are four from the early 1850s, before the painter had ever visited Vermont. They feature views of New York’s Hudson River. “So now,” said Pierce, “our Hudson River painter has a Hudson River painting.”