Social Security is rapidly approaching insolvency. The retirement trust fund is seven years from exhaustion, and the theoretically combined trust funds are nine years from running out. Without legislative action, retirees will face an estimated 24 percent across-the-board benefit cut in late 2032. Restoring long-term solvency will require slowing the growth of benefits, raising revenue, or some combination.

Under the Social Security program, benefit levels are increased every January through an annual Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA), which is meant to ensure benefits keep pace with inflation. All beneficiaries receive this annual COLA based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W).

In the past, several plans have proposed modifying COLAs to lower future program costs. A common proposal involves using a more accurate measure of inflation known as the chained CPI (C-CPI-U) to calculate COLAs.1 Another proposal would means-test the COLA to eliminate increases in years beneficiaries have high incomes.2

This Trust Fund Solutions Initiative white paper offers a new option to cap COLAs at the amount received by a relatively high earner.3 Under the proposed COLA cap, all beneficiaries would continue to receive an annual COLA, but that COLA would be limited in size for those with the largest benefits (and highest lifetime income). A COLA cap could be enacted in place of or in combination with other COLA changes.

Karen E. Smith at the Urban Institute modeled this proposal using the DYNASIM4 model.4 Using the Urban analysis, we find that capping annual COLAs would:

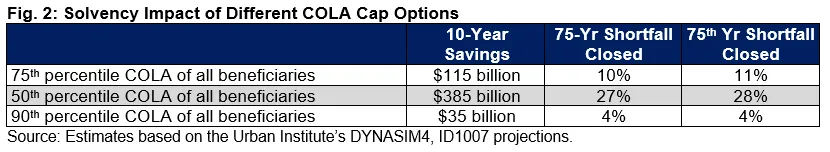

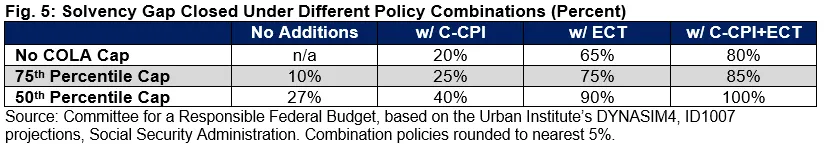

Close one-tenth of Social Security’s solvency gap and save $115 billion over a decade, with the cap set at the COLA received by the 75th percentile retiree.

Close one-twentieth to one-quarter of the gap if set at the 50th or 90th

Increase the progressivity of Social Security, only affecting high earners.

Increase payable benefits for those in the bottom three quintiles.

Retain inflation protection for an adequate level of Social Security benefits while generating immediate savings and avoiding work disincentives.

If paired with other benefit and/or revenue Trust Fund Solutions, a COLA cap could be a rapid, thoughtful, and progressive way to help restore solvency and put Social Security on a sustainable path.

The Social Security COLA Cap

Social Security benefits are adjusted upward each year with the CPI-W through annual COLAs.5 COLAs are meant to prevent benefits from eroding due to inflation. Before the COLAs are applied, initial benefits grow each year at roughly the rate of wage growth.

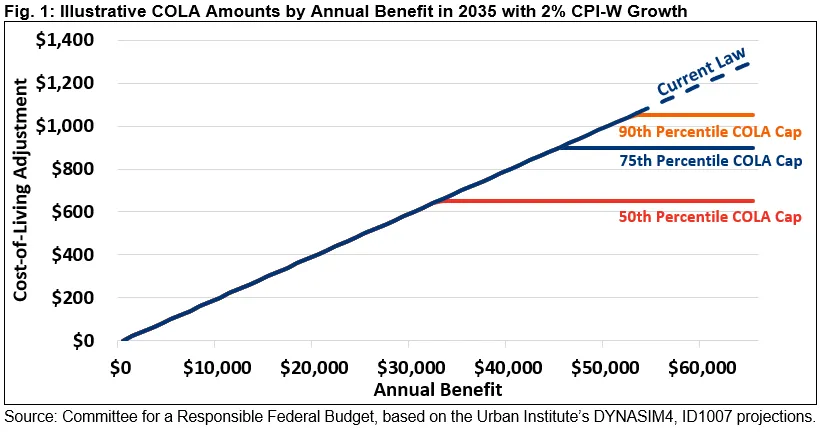

Under this Trust Fund Solution, the COLA would be limited each year to the amount received by a beneficiary with a relatively high benefit level. All beneficiaries would continue to receive a COLA under this proposal – many would receive the same COLA as under current law – and initial benefits would continue to be indexed to wage growth as under current law. However, beneficiaries that would otherwise receive a COLA above the cap – retirees with the largest benefits and the highest lifetime incomes – would instead receive a COLA equal to the cap.

For example, if CPI-W growth in 2035 were 2 percent and the cap was set at $900, a retiree with a $50,000 benefit who would receive a $1,000 COLA under current law would instead receive $900. Those with $45,000 or less in benefits would receive the same COLA as under current law.

Policymakers could set this cap at any desired level based on solvency, distributional, and other targets and trade-offs. The cap could also be calculated in a variety of ways (see Appendix III). For this analysis, we assume the cap is set based on a percentile of workers’ Primary Insurance Amounts (PIAs) and adjusted upward or downward based on collection age and benefit type.6

Karen E. Smith of the Urban Institute modeled a COLA cap set at the COLA of the 75th percentile of all benefits – meaning it would affect the top quarter of beneficiaries in a given year. Smith also modeled two alternative caps set at the COLAs received at the 50th and 90th percentiles of benefits.

A COLA Cap Would Improve Solvency

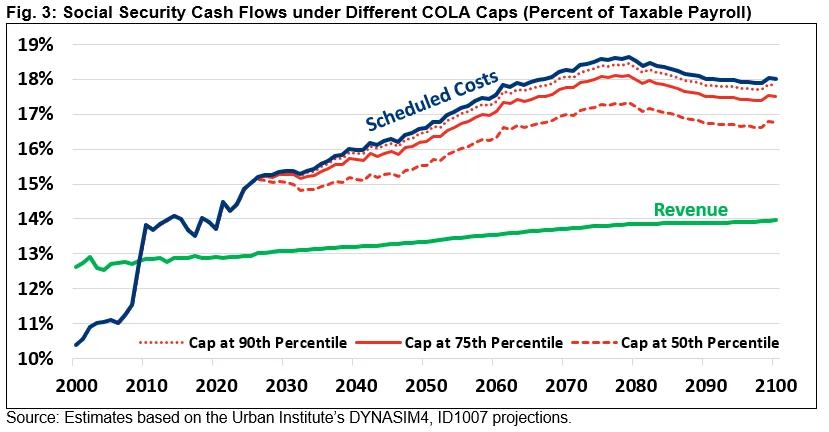

A COLA cap would generate immediate savings and meaningfully reduce Social Security’s funding gap. Set at the 75th percentile of all benefits, the COLA cap would save $115 billion over a decade and close one-tenth of Social Security’s 75-year solvency gap. Set at the 50th or 90th percentile, the cap could save $35 billion to $385 billion over a decade and close between one-twentieth and one-quarter of the 75-year solvency gap.

A COLA cap at the 75th percentile of benefits would reduce Social Security’s shortfall by 0.3 percent of taxable payroll over 75 years and 0.4 percent of payroll in 2098. A cap set between the 90th percentile and 50th percentile would save between 0.1 and 0.9 percent of payroll over 75 years and 0.2 to 1.1 percent in 2098. As a share of annual economic output, the cap would reduce Social Security’s annual deficit by 0.1 to 0.4 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2098.

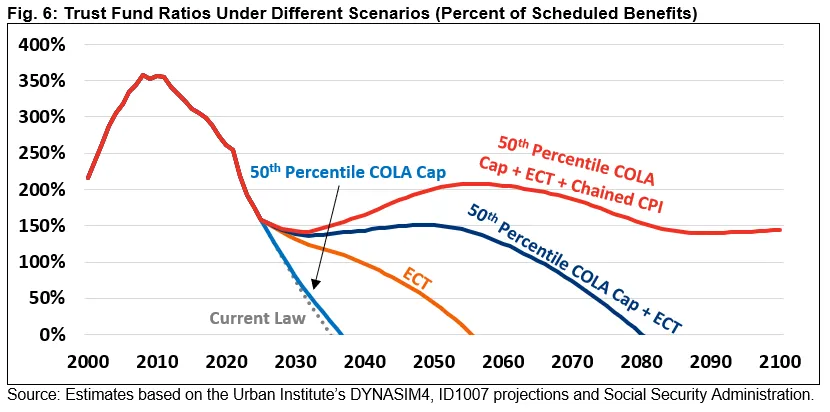

Because policymakers have waited so long to act, a COLA cap would do little to delay insolvency on its own. However, the COLA cap could meaningfully delay insolvency if paired with other benefit and/or revenue reforms. For example, adopting the COLA cap at the 50th percentile in combination with an Employer Compensation Tax (ECT) – which itself would extend solvency 20 years – would delay insolvency by 45 years to 2080. See Appendix I for more policy alternatives.

A COLA Cap Would Increase Progressivity and Mostly Affect High Earners

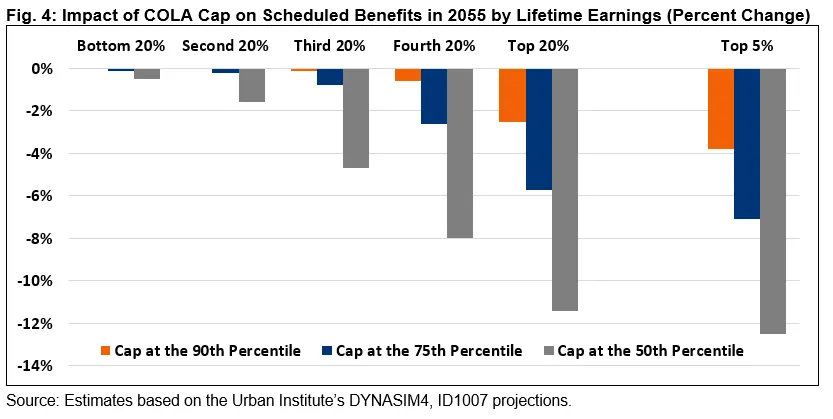

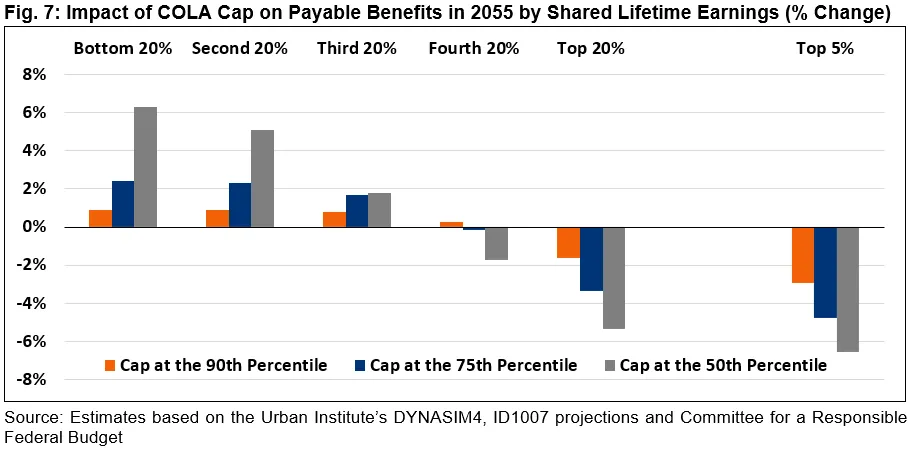

A COLA cap would make Social Security more progressive, only meaningfully reducing scheduled benefits for higher earners while increasing payable benefits for lower earners. In a given year, most beneficiaries would see no change in their COLAs, while the COLA cap would progressively constrain benefit growth for higher earners.

Compared to scheduled benefits, a cap at the 75th percentile of benefits would have virtually no effect on the poverty rate and a minimal effect on the benefits of those in the bottom 60 percent of earners.7 The effect would be modest at the fourth quintile – less than a 3 percent reduction in benefits in 2055. Benefits would be 6 percent lower for the top quintile, including 7 percent lower for the top 5 percent of earners. The cap would likely be even more progressive on a lifetime basis since high earners tend to live longer and the COLA savings grow cumulatively with age.

Different caps would have different distributional outcomes. For example, setting the cap at the 50th percentile would largely insulate the bottom two income quintiles while reducing scheduled benefits by almost 5 percent for the middle quintile and over 11 percent for the top quintile. Setting it at the 90th percentile would have little effect on the bottom four quintiles while the top quintile would face a 2 percent reduction compared to what is scheduled.

Importantly, the COLA cap would actually increase payable benefits for most beneficiaries.8 Social Security cannot legally pay benefits in excess of revenue once the trust fund is exhausted; this necessitates an across-the-board benefit cut. Because the COLA cap would improve solvency and thus shrink that cut, the 75th percentile cap would increase payable benefits by about 2 percent for those in the bottom three quintiles. Only those in the top quintile would see a meaningful reduction in payable benefits – which would total about 3 percent. The cap would also reduce poverty on a payable-benefits basis. Appendix II details the effects relative to payable benefits.

A COLA Cap Could Be a Thoughtful Way to Stem the Rise in Program Costs

Enacting a COLA cap is a way to limit benefits at the top without reducing seniors’ incentives to work or save while ensuring seniors maintain an adequate standard of living as they age. Specifically, a COLA cap would limit adjustments to the retirees with the largest benefits and the highest lifetime earnings – those likely to have the most income and wealth.

Since the cap is based on current Social Security benefits and (by proxy) lifetime earnings,9 rather than current income, it would not reduce benefits for seniors because they choose to work in old age. Avoiding disincentives to work is a key advantage of a COLA cap as greater work in old age can strengthen the solvency of the Social Security system, accelerate economic growth, and bolster seniors’ financial security and overall well-being.10

By setting an upper limit on COLA amounts, a COLA cap would retain full inflation protection for most beneficiaries – in fact, most seniors would continue to see their benefits outpace inflation, since the CPI-W overstates inflation by an estimated 0.3 percentage points per year on average. All beneficiaries would see their benefits rise in nominal terms each year.

Moreover, those who do not receive full (or excessive) inflation protection would still see inflation protection for an adequate level of benefits. In 2026, under the 75th percentile COLA cap, each beneficiary’s first $33,000 in benefits – an amount twice as high as the poverty threshold – would keep pace with CPI-W inflation. By 2060, each beneficiary’s first $111,000 in benefits – an amount three times as high as the poverty threshold – would keep pace with CPI-W inflation.

Capping COLA amounts would also allow policymakers to spread benefit adjustments across generations more fairly. High-income seniors from the baby boom generation – people who paid lower payroll taxes over a portion of their career and who benefitted from the system when it was out of balance – would share in some of the solvency solution. This reduces the relative burden on future seniors and current workers.

A COLA cap would have an additional advantage in that it would introduce a new measure of flexibility into the Social Security system. It is fully dialable – policymakers could adjust it as needs change. If policymakers need to find additional savings, the COLA cap could be progressively tightened to further slow the rise in costs. Alternatively, if lawmakers wanted to provide additional protection to particular groups of beneficiaries, the cap could be increased or applied differently across categories of beneficiaries.11

In the context of the Social Security retirement trust fund facing insolvency in just seven years, the potential for upfront savings is an important advantage of a COLA cap. It would quickly reduce program costs and enable lawmakers to phase in other necessary benefit and revenue reforms over longer periods of time.

Conclusion

With the insolvency of Social Security’s retirement trust fund just seven years away, policymakers have lost much of their capacity to slowly phase in changes to benefits for new beneficiaries. Reforms that can quickly stem cost growth and increase revenues are needed to avoid a 24 percent across-the-board benefit cut in late 2032.

Numerous options exist to restore Social Security solvency and improve the program – many of them well-known. But policymakers should also consider more novel solutions.

A COLA cap could meaningfully and quickly improve the solvency of Social Security’s trust funds while concentrating adjustments on those most able to bear them, maintaining full inflation protection for most beneficiaries, continuing to maintain inflation protection on an adequate level of benefits for all beneficiaries, and ensuring solvency solutions are spread over more generations. It would do so without meaningfully weakening work incentives in the program or enacting nominal benefit cuts or freezes.

A COLA cap on its own will not be sufficient to restore Social Security solvency.12 However, setting the cap somewhere between the median and 90th percentile of benefits could close between one-twentieth and one-quarter of Social Security’s 75-year solvency gap and reduce a similar proportion of its annual shortfalls. In combination with other benefit and/or revenue reforms, the cap could help to avoid the looming 24 percent benefit cut and secure Social Security for generations.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget does not endorse any particular solution to restore solvency to Social Security and Medicare. The COLA cap presented in this paper should be added to the library of potential options lawmakers consider when crafting a broader reform package. The insolvency of the Social Security trust funds is less than a decade away, and trust fund solutions are urgently needed.

Appendix I – Combining a COLA Cap with Further Reforms

Although the COLA cap on its own would only modestly extend and improve solvency, it could be combined with other changes to further strengthen the trust funds.

Whereas the 75th percentile COLA cap would close 10 percent of the 75-year solvency gap on its own, for example, it would close 25 percent in combination with adopting the more accurate Chained CPI for the remaining COLA, 75 percent in combination with our recently introduced Employer Compensation Tax (ECT), and 85 percent in combination with both. The 50th percentile cap would close 27 percent of the shortfall on its own, 40 percent with Chained CPI, 90 percent with the ECT, and the entire solvency gap with both the Chained CPI and ECT.13

The combination of the COLA cap and other reforms could also delay the insolvency date by more than the sum of their parts. Whereas the 50th percentile cap would delay insolvency by one year and the ECT by 20 years, for example, the two together would delay insolvency by 45 years, to 2080. Also adopting Chained CPI – which itself would only delay insolvency by one year – would ensure sustainable solvency through 2100 and beyond.

Similarly, while the 75th percentile cap would delay insolvency by less than a year, it would delay insolvency by 26 years in combination with the ECT and 41 years with the ECT and Chained CPI.

Appendix II – Distributional Impact of COLA Caps Relative to Payable Benefits

Relative to payable benefits, a COLA cap would increase all benefits by reducing the across-the-board cut required upon insolvency. The increase in the initial benefit would be countered by a reduction in the growth of benefits due to the cap.

Under the 75th percentile cap, payable benefits would rise by about 2 percent for those in the bottom three income quintiles. Those in the fourth quintile would face almost no net change in benefits, while those in the top quintile would face a 3 percent reduction – including a 5 percent reduction at the very top.

A cap at the 50th percentile would result in larger increases and larger reductions in payable benefits, since it would do more to slow benefit growth and more to improve solvency. In 2055, this cap would boost total benefits by 6 percent for the bottom quintile, 5 percent for the second quintile, and almost 2 percent for the middle quintile. Those in the fourth quintile would face a 2 percent reduction and those in top quintile would face a 5 percent reduction, including a 7 percent reduction at the very top of the income spectrum.

A cap at the 90th percentile would lead to smaller increases and smaller reductions in payable benefits, as it would slow benefit growth less and thus improve solvency less. Those in the bottom three quintiles would see a slight increase in their payable benefits – less than 1 percent. Meanwhile, those in the top quintile would experience a 2 percent reduction in payable benefits.

A COLA cap could increase payable benefits much more if combined with other reforms that fully restore Social Security solvency. For example, the combination of adopting the COLA cap at the 50th percentile, Chained CPI, and an Employer Compensation Tax would boost payable benefits by 23 percent at the bottom quintile, 19 percent in the middle, and 12 percent at the top.

Appendix III – Design Options for the COLA Cap

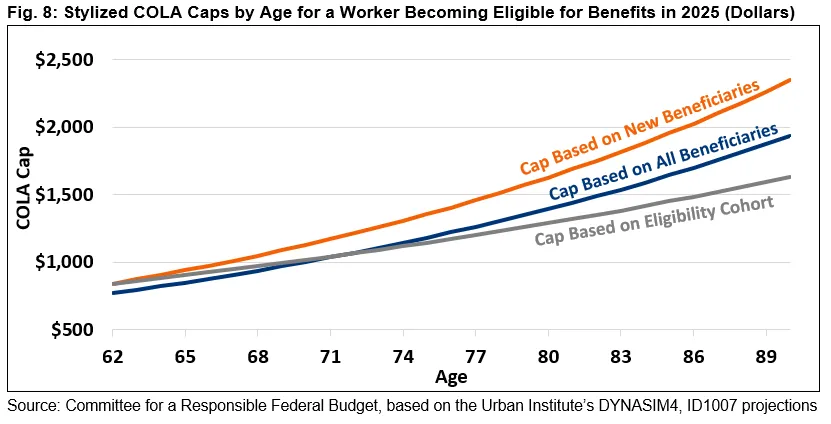

This Trust Fund Solutions Initiative paper suggests a concept of capping a COLA at a specific dollar amount, and then illustrates one possible way to set the cap. Specifically, it suggests setting the cap to essentially reflect the 75th (or 50th or 90th) percentile of all COLAs, based on PIAs and adjusted upward or downward based on collection age and type of benefit. At the 75th percentile, this effectively means the cap would be binding for a quarter of all beneficiaries each year.

However, the cap could be set in a number of other ways. One option would be to set the cap based on the percentile benefit within each eligibility cohort.14 At the 75th percentile, this would effectively mean the cap was binding for a quarter of beneficiaries in each age group. This design would have a more progressive effect on lifetime benefits, since higher earners tend to live longer.

An alternative would set the cap based on new beneficiaries. Because newer cohorts tend to have higher benefits than previous ones, this cap would be binding for a larger number of young beneficiaries each year and a declining number of older beneficiaries as their benefits erode relative to new benefits. Effectively, this option would loosen the cap on older beneficiaries, who may be in more need of inflation protection as they’ve outlived their savings and work capacity.

The cap could also be set in other ways – for example as a percentage or multiple of the median benefit, of the average wage, or of the poverty line.

A simpler approach would set the COLA at a specific dollar amount and then index the cap over time. A wage-indexed cap would affect a similar share of beneficiaries over time, though it would become less binding over time if combined with reforms to slow the growth of initial benefits.

Endnotes

1 The CPI-W tends to overstate inflation by about 0.3 percentage points per year on average because it represents the spending patterns of just 30 percent of consumers and fails to fully account for the substitution of cheaper goods and services for more expensive ones as relative prices change. The C-CPI-U, on the other hand, incorporates the full effects of changing spending patterns and covers 90 percent of the population. Measuring COLAs using the C-CPI-U – which is already used to index the tax code – would close about one-sixth of Social Security’s funding gap. See Measuring Up: The Case for the Chained CPI to learn more.

2 In addition to substituting the C-CPI-U for the CPI-W when calculating COLAs, the late Representative Sam Johnson’s Social Security Reform Act of 2016 would have eliminated COLAs completely for beneficiaries in years when their annual incomes exceeded $85,000 ($170,000 if married).

3 The Trust Fund Solutions Initiative is a project of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget to develop and analyze new policy options to help address trust fund solvency and improve the Social Security, Medicare, and highway programs. These options should be considered along with a menu of others. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget does not endorse the options outlined in this paper or in others.

4 The simulations were run on DYNASIM4, an Urban Institute projection microsimulation model. It uses surveys and administrative data to project workers through 2100 and broadly aligns to the Social Security Actuaries’ projections. Simulations assumed a 2025 start date and used the assumptions of the 2024 Social Security and Medicare Trustees Reports. Due to legislative and other reasons, the Trustees now estimate a meaningfully larger funding gap for both programs. We are enormously grateful to Karen E. Smith from the Urban Institute for modeling these options and patiently dealing with our many questions. For more about DYNASIM4, see Cosic, Johnson, and Smith, Urban’s Dynamic Simulation of Income Model 4.

5 Cost-of-Living Adjustments, effective in December of every year, are equal to the percentage increase in the average of the CPI-W of the third quarter of the current year from the average of the third quarter of the last year in which a COLA became effective. To learn more, please see Latest Cost-of-Living Adjustment.

6 The cap could be set and applied in any number of ways. Under the version we considered, the cap would be set equal to the COLA received by the 75th percentile beneficiary based on their Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) – the benefit a retiree would receive if they claimed at their Full Retirement Age (FRA). As with the benefit itself, the cap would be adjusted upward or downward based on collection age. For example, the cap would be reduced by 30 percent for those who began collecting at age 62 and increased by 24 percent for those who began collecting at age 70. Similarly, the cap would be adjusted for benefit type. For example, it would be half as high for a spousal benefit.

7 Under a COLA cap set at the 75th percentile benefit, DYNASIM4 projects the overall poverty rate among the aged and disabled would remain unchanged at 6 percent in 2055. For some groups, such as those without a high school education, the poverty rate would rise slightly by no more than 0.1 percentage points. With a COLA cap set at the 50th percentile benefit, overall poverty would rise by 0.1 percentage points and by no more than that amount among any particular subgroup. Under all other options modeled, lower-income beneficiaries are largely shielded from changes to benefits such that projected poverty rates are not meaningfully affected.

8 This estimate compares payable benefits under current law to payable benefits in case of enactment of the COLA cap. In both cases, trust fund insolvency will lead to an automatic across-the-board benefit cut. In the case of enactment of the COLA cap, the across-the-board cut would be smaller but also relative to lower overall benefits.

9 Social Security benefits are determined by applying a progressive formula to a worker’s average career earnings. Although this results in a progressive replacement rate, it also leads to higher benefits for those with high lifetime earnings relative to the benefits of those with lower lifetime earnings. As a result, those with higher lifetime earnings also receive higher COLAs – which are calculated as a percentage of benefits. A COLA cap thus effectively means-tests COLAs based on beneficiaries’ average lifetime earnings.

10 Butrica, Barbara, Karen E. Smith, and C. Eugene Steuerle. 2006. “Working for a Good Retirement.” Urban Institute Discussion Paper 06-03. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/working-good-retirement; Kuhn, Michael and Klaus Prettner. 2022. “Rising Longevity, Increasing the Retirement Age, and the Consequences for Knowledge-based Long-run Growth.” Economica 90 (357): 39-64. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ecca.12445; Bronshtein, Gila et al. 2018. “The Power of Working Longer.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 24226. https://www.nber.org/papers/w24226; Patacchini, Eleonora and Gary V. Engelhardt. 2016. “Work, Retirement, and Social Networks at Older Ages.” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College Working Paper 2016-15. https://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/wp_2016-15.pdf; Sewdas, Ranu et al. 2020. “Association Between Retirement and Mortality: Working Longer, Living Longer? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 74 (5): 473-480. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7307664/; Li, Jiannan, Bocong Yuan, and Junbang Lan. 2021. “The Influence of Late Retirement on Health Outcomes Among Older Adults in the Policy Context of Delayed Retirement Initiative: An Empirical Attempt of Clarifying Identification Bias.” Archives of Public Health 79 (59). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8077823/; Banks, James et al. 2025. “The Impact of Work on Cognition and Physical Disability: Evidence from English Women.” Labour Economics 94. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0927537125000545.

11 As one example, basing a COLA cap on the benefit levels of new rather than all beneficiaries would effectively ‘loosen’ the cap for older retirees – people who are more likely to have exhausted their savings and who are less able to identify alternative sources of income.

12 Technically, an extremely low cap – one close to $0 – might be sufficient to fully restore solvency. But this policy would be more akin to eliminating COLAs altogether than to capping them.

13 The policy combinations close nearly an identical share of the 75th year shortfall as the 75-year solvency gap.

14 Eligibility cohort refers to the year in which a beneficiary first becomes eligible for benefits. For retired beneficiaries, this is the year they attain age 62. For disabled beneficiaries, it is the year they become disabled. For widow(er)s, it is the later of the year they attain age 60 and the year of the death of their insured spouse.