Fridley Public Schools Superintendent Brenda Lewis abruptly paused the hiring of a dozen international employees last month when President Donald Trump announced a new fee for their work visas, the latest turn of events in his mass overhaul of immigration policies.

Fridley Public Schools has been hiring more international teachers each year since 2023, especially in the special education department, and is just one of many employers in Minnesota whose reliance on foreign workers was shaken by Trump’s announcement.

The president issued an executive order in mid-September requiring employers to pay $100,000 for each new international employee who needs a H1-B visa to live and work in the United States. The visa used to cost from $2,000 to $5,000 per employee, depending on the employer’s size.

“We can’t afford that,” Lewis told Sahan Journal.

There are still many questions about how the government will spend money from the increased fees, and whether certain industries will be treated differently, said some local immigration attorneys. They also said the fee will put a strain on industries that rely on H1-B workers to fill worker shortages, such as teachers and nurses.

“They [Trump administration] don’t realize that it’s actually harming a lot of other industries,” said John Medeiros, a Minneapolis-based immigration attorney.

There was chaos in airports a few days after Trump’s announcement as H1-B workers abandoned travel plans and rushed back to the United States, according to news accounts from around the country. Immigration attorneys in Minnesota fielded a rush of calls from H1-B clients and employers that weekend.

“We were telling people to get back here really fast,” Medeiros said. “So it was a huge disruption.”

What’s an H1-B visa?

The H1-B program was created by Congress in 1990 to offer a way for employers to temporarily hire immigrants to work in specialty occupations that require at least a bachelor’s degree. H1-B visas expire in three years, and can be renewed for another three years. It’s possible to extend the visa longer than six years with limited exceptions. Employers apply for the H1-B petition and cover the cost of the visa.

To enter the chance to receive an H1-B visa, employers submit a request to the federal lottery. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services agency randomly selects which employers then get to file an actual H1-B application. The H1-B lottery has 85,000 slots open next year, according to the agency.

Generally, universities, nonprofits and government research organizations are exempt from the lottery, so they can submit petitions at any time. The federal citizenship agency reviews and approves applications based on several factors, including an employee’s level of education and their occupation’s specialty.

The Trump administration said the new fee will prevent misuse of the H1-B visa program and address national security threats. It will apply to new H1-B applicants outside of the United States who file petitions for the visa on or after Sept. 21, 2025.

“The H-1B nonimmigrant visa program was created to bring temporary workers into the United States to perform additive, high-skilled functions, but it has been deliberately exploited to replace, rather than supplement, American workers with lower-paid, lower-skilled labor,” read the executive order.

The new fee does not apply to individuals already in the United States on an H1-B visa who are seeking an extension. It also does not apply to others who are in the country on other immigration visas, such as an international student visa, who want to change them into an H1-B visa, according to the latest update Monday from the Trump administration.

The president’s update said exemptions to the fee will be granted in “extraordinarily rare circumstance,” such as:

Workers in a field of “national interest.”

Workers who don’t pose a threat to the United States.

For jobs that “no American worker is available to fill the role.”

For jobs where employers can prove that the fee “would significantly undermine the interests of the United States.”

Employers can email evidence to H1BExceptions@hq.dhs.gov and request an exemption from the fee.

More details about the new fee are supposed to be released in a couple of months before the H1-B lottery, which will occur sometime next spring, said Loan Huynh, a Minneapolis-based immigration attorney.

A federal lawsuit has been filed to stop the enforcement of the new fee, stating that it is unlawful and harmful to U.S. businesses. Minnesota immigration attorneys say the changes are not focused on addressing issues in the immigration system, and that they will close a pathway for immigrants who hope to come to the United States.

“It’s not clear to us in regards to what the administration is addressing, because the implementation of $100,000 does not really address what it alleges is the misuse of the program here,” Huynh said. “It didn’t change anything within the H1-B program.”

Retail, medical and education industries affected

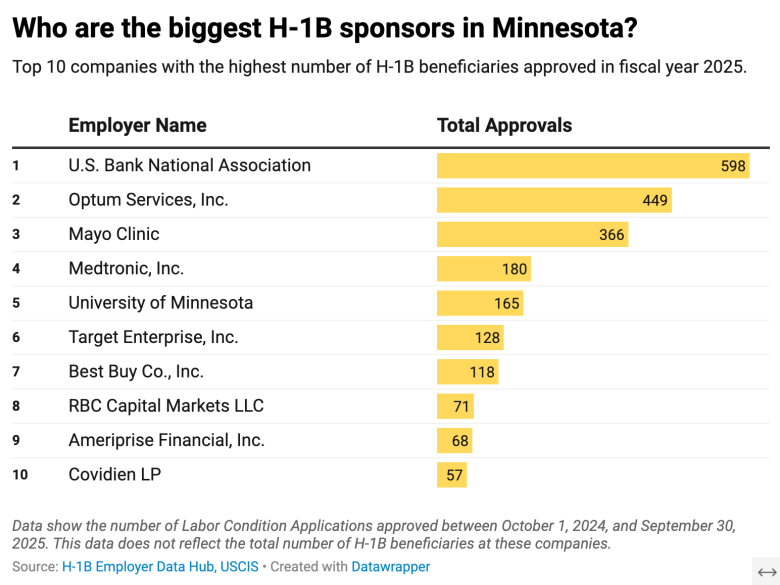

Some of the largest H1-B employers in Minnesota include Target, BestBuy, the University of Minnesota, Mayo Clinic and U.S. Bank, which received between 128 to 598 H1-B approvals this year, according to data from the federal citizenship agency. School districts are also among the top H1-B employers, including the Lakes International Language Academy, SouthWest Metro Intermediate District 288 and Fridley Public Schools.

Sahan Journal reached out to the top 10 H1-B employers in Minnesota for comment, but did not receive a response from nine of the companies; Ameriprise Financial Inc. declined to comment.

Shannon Peterson, executive director at the Lakes International Language Academy, said the new fee caused confusion, prompting parents to ask if some teachers would have to leave school. The academy, a public charter school that provides kindergarten through fifth-grade Chinese and Spanish full immersion education, has hired H1-B teachers for several years.

“Not only do these teachers have the skillset, education and experience that we need, they’re also native speakers of the languages that we’re using to teach,” she said. “There’s no way we can pay [the new fee]. In fact, it’s probably almost double the average of what our teachers make.”

Lewis said the number of H1-B workers at Fridley Public Schools district has grown to about 70 teachers as of this year. She submitted only one H1-B petition after requesting an exemption from the new fee. She’s waiting to hear back from the federal citizenship agency whether the fee will be waived before deciding if she should submit the other petitions she put on pause.

Some school officials said they hope the government won’t require fees for educators because generally schools are exempt from the lottery system that applies to other employers.

Lewis said she told the international employees whose H1-B petitions were paused that she is determined to find a way forward by teaming up with elected officials and potentially joining a lawsuit challenging the new fee.

“I just think this is an exercise of nonsense,” she said of the new fee.

Anjuli Cameron, chief executive officer of the SEWA-Asian Indian Family Wellness, a nonprofit dedicated to family wellness in South Asian communities in Minnesota, said the H1-B visa program is a major pipeline for Indian immigrants coming to Minnesota.

“We definitely see that reflected in multiple generations of the community now, having high-level professionals who have come through that pathway,” she said.

Across the country, Indian nationals have consistently accounted for over 70% of immigrant workers who received H1-B visas over the past ten years, according to data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Eagan resident Sai Kancharla, 30, has an F-1 visa with Optional Practical Training, which allows international students to legally work in the country. He believes some Indian residents in Minnesota are already facing other immigration policies and hardships in the job market. The new H1-B visa fee is an added burden, he said.

However, he said a potential benefit of the new fee is that immigrants who already live in the United States could have a greater chance of receiving an H1-B visa because there might be less competition with applicants from outside the country. He plans to apply for the H1-B visa in next year’s lottery.

Kancharla came to the United States in 2017 as a student, pays taxes, invested in his education and career, and is starting a family.

“If somebody else is applying for the H1-B outside, legally or illegally – I’m not sure – they’re taking over my chance to get it,” he said.

Thirty-one-year-old Eden Prairie resident Raju Bommana, who has been on a H1-B visa for the past four-and-a-half years, received text messages from concerned friends when Trump issued the executive order.

“It did create a panic mode,” he said.

Bommana said a wave of relief washed over him when the Trump administration issued new guidance a few days later, clarifying that the fee would only apply to new applicants.

Although the new fee won’t affect Bommana, he’s worried it will decrease the Indian population in Minnesota over time. The Census Bureau estimated that in 2023, around 32,000 Minnesota residents were born in India. The bureau does not analyze how many immigrated on an H1-B visa.

The new fee will make it harder for others to follow that path, Cameron said: “We’re going to feel it in our community.”

Anjuli Cameron, CEO of the SEWA-Asian Indian Family Wellness center in Brooklyn Center, pictured on Oct. 21, 2025. Credit: Dymanh Chhoun | Sahan Journal

Anjuli Cameron, CEO of the SEWA-Asian Indian Family Wellness center in Brooklyn Center, pictured on Oct. 21, 2025. Credit: Dymanh Chhoun | Sahan Journal