The Athletic has live coverage of NFL Week 8.

To get some of the most specialized tight end teaching in the world, a young player first has to get through Maggie, Sheila and Alli.

These are Logan Paulsen and his wife Kelly’s rescue dogs, all different ages and sizes, all at the door of their comfortable northern Virginia home to greet his students for another day of film study and training.

Paulsen, 38, spent a decade playing tight end in the NFL. He was never a star in the passing game but could seal a block better than most. Coaches always talked about him as a glue guy or an indirect coach they wanted on their roster, but he also got caught in waves of roster-churn cuts in the middle and later years of his career and became a journeyman rotating between multiple teams. Such is life for a No. 2 or 3 tight end.

Now, Paulsen teaches young tight ends the more complicated elements of the position as they prepare for the NFL Draft. His longtime agent and friend, Steve Caric, often sends clients to him in the winter and early spring for extra work, and Paulsen welcomes them into his home and his brain.

He has trained Terrance Ferguson, the Rams’ second-round pick this spring; Jake Tonges, the former undrafted free agent who recently filled in for All-Pro George Kittle in San Francisco while Kittle recovered from a hamstring injury and averaged about four catches per game with three touchdowns; and more than a dozen others over the last few offseasons.

The son of an engineer in a family of doctors and architects, Paulsen likes to understand how and why things work. His innate curiosity informed his mastery of less-heralded details like protections and blocking layers as a player, and still informs his teaching.

“Football is constantly evolving,” he said. “I can’t sit here and have a guy in my house talking about the expectations of the NFL if I don’t understand the direction that the NFL is going. Part of me is just like, I’m just chasing (knowledge) because it’s fun, and also because I want to hold a standard of teaching.”

Over weeks and even months, players break down hours of film with Paulsen in his living room and train on local fields near his house. When it rains or snows, he takes the players to the Dulles Sportsplex, an indoor sports and recreation facility, where they run routes a few yards away from youth soccer camps and grandmas walking with their weights.

There is no shortage of clientele. These days, there is a bigger spotlight than ever on tight ends, both in pop culture and through a schematic resurgence across the NFL. Every team is looking for more than one good tight end, or trying to build one through training.

“When I was in college and watching tight ends, I feel like a majority of NFL fans could probably name maybe five to 10 starting tight ends in the NFL,” Kittle said. “Nowadays, almost every fan can name probably 28 out of the 32 NFL starting tight ends. … I just think that the overall level of tight end play has increased so much that every team now is searching for a really good (one).”

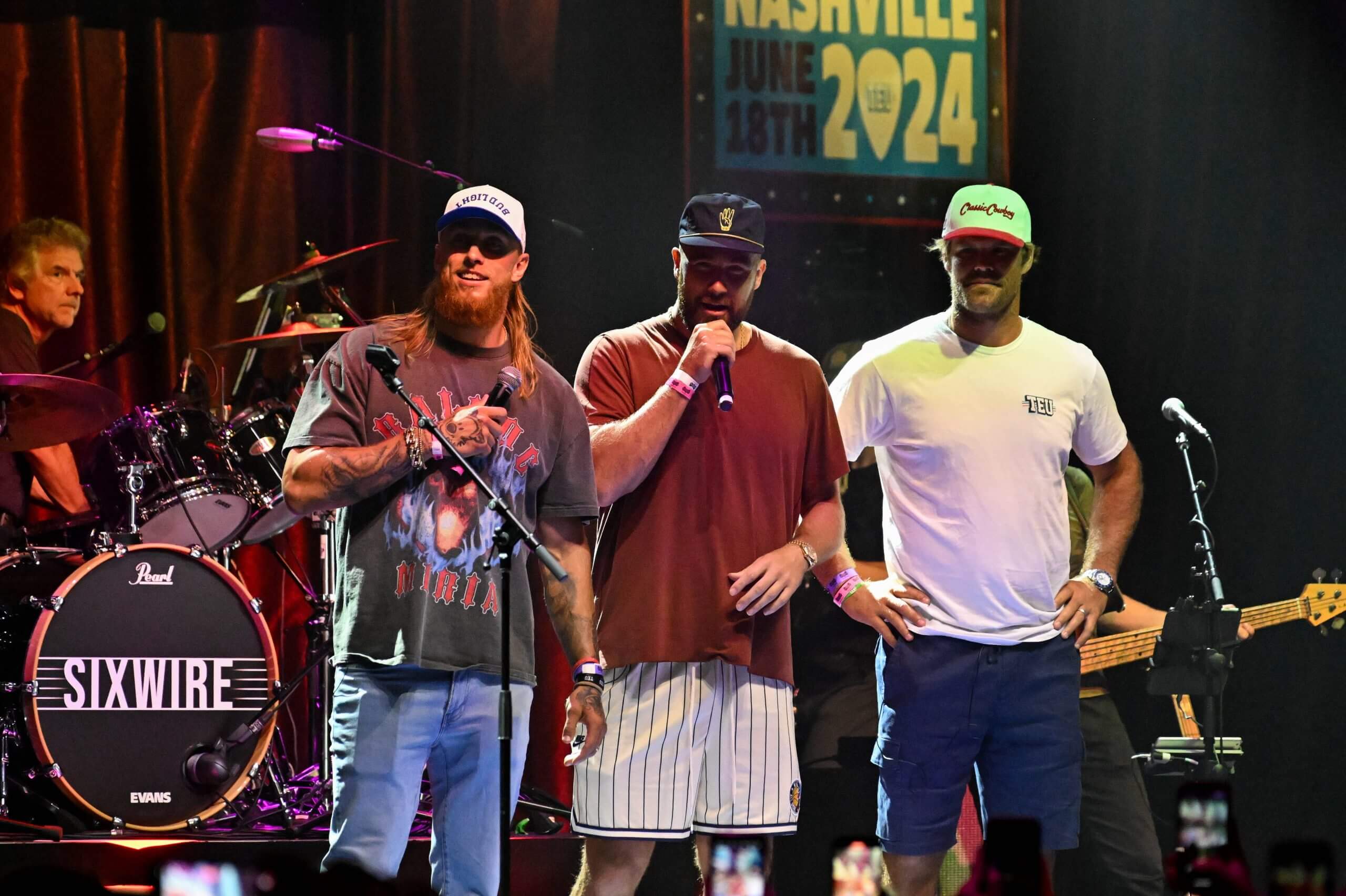

Kittle, the face of Sunday’s “National Tight Ends Day,” has worked for years to bring more attention to the position. Along with Chiefs All-Pro Travis Kelce and retired tight end-turned Fox NFL analyst Greg Olsen, Kittle co-founded an annual multiday summit for tight ends in 2021, called Tight End University. The three-day Nashville event (like the position) has grown in popularity and recognition — especially so after Taylor Swift, the most famous pop star on the planet who also happens to be engaged to Kelce, gave an impromptu performance at one of its parties last summer.

George Kittle, Travis Kelce and Greg Olsen speak on stage during the Tight Ends & Friends Concert in Nashville. (Carly Mackler / Getty Images)

But most important to Kittle about TEU is the teaching, learning and sharing of techniques among attendees.

The tight end position has evolved significantly, but there’s still a little old-fashioned magic to it. Its most passionate and informed teachers, current and former players say, usually aren’t assistant coaches in an NFL building but players. Tight ends fiercely preserve their own history and the nuances of their position, preferring peer-to-peer coaching to more traditional coach/player dynamics. The lore of the position is passed between players like travelers telling tales at a campfire.

“That ethos of passing of information is what kinda made me want to do Tight End U,” Kittle said. “That was a big part of that, sharing information, because I want the tight end position to continue to grow and be highlighted.”

Stewards of the position like Kittle and Paulsen aim to give all they know to a new generation. Sharing knowledge comes in many forms.

When Los Angeles Rams coach Sean McVay heard that Ferguson was training with Paulsen before the 2025 draft, his ears perked up. McVay already loved Ferguson as a draft prospect but acknowledged he was raw in some areas, such as blocking, and was more frequently used in the passing game at Oregon.

Knowing Ferguson had spent time with Paulsen to specifically learn more about blocking techniques made drafting him in the second round an easy decision for McVay. He had coached Paulsen in Washington from 2010 to 2015; he admits that sometimes it was Paulsen coaching him.

“He was one of my all-time favorite players I’ve ever had a chance to coach,” said McVay. “For (Ferguson) to have spent the last four months with him working on some different things that allowed Logan to be such a successful player above the neck physically, mentally, emotionally, all those things — he’s been in good hands.

“The coaching is going to go down now that he’s around me.”

Preserving and passing along the finer teaching points of tight end blocking is especially personal to Paulsen. For one, that’s part of why he stuck around in the NFL for almost 10 seasons. As gifted at catching passes as many young tight ends are in this era, and as prioritized as those traits have become in NFL offenses, blocking well is timeless and keeps a tight end on the field for every down.

San Francisco tight end Jake Tonges, who has trained with Logan Paulsen, performed well when 49ers star George Kittle was injured. (Ezra Shaw / Getty Images)

Offenses started shifting toward using more 11 personnel (three receivers, one tight end, one running back) a little over a decade ago. In 2017, McVay and the Rams used 11 personnel at a higher frequency than any other NFL team and exploited the popular defensive schemes of the time from those formations.

That season especially served as an offensive catalyst for the sport. McVay’s offense was both explosive and productive, and NFL owners quickly saw that using so many three-receiver sets benefited the executives who built their teams. Quarterbacks were getting better and more expensive, and it was easier to find effective receivers at all levels of the draft and play them more quickly on their cheaper rookie deals. McVay’s offense inspired imitators as his assistant coaches spread across the NFL over the next few seasons, and while new defensive schemes famously evolved to counter it, 11 personnel seemed a permanent fixture of a league hell-bent on passing.

From 2017 to 2025, offenses have used 11 personnel at a frequency of at least 57.5 percent, with the highest usage points coming in 2018 (after the NFL had a year of film on McVay’s offense) and in 2023.

In 11 personnel, the lone tight end in the formation might be an outlier — a player who can dominate in both the passing game and as a blocker, as Kittle does — but typically that single tight end was decent with his hands and might have needed to supplement as a blocker what the receivers lacked in size and strength.

But tight ends started getting better and more specialized as pass catchers in the collegiate ranks. Older tight ends joke that bigger, longer guys used to become offensive tackles once they grew into their bodies in high school and college but remained tight ends if they stayed skinny. Now, Kittle said, kids are growing up wanting to specifically play tight end and specializing much earlier.

“I took two snaps at tight end in high school. Two. And they were both pass plays,” said Kittle. “Then at Iowa they just put me there because I was an athlete. Thank God it stuck.”

College football offensive schemes began to maximize the pass-catching tight end where previously the trend was four-receiver (10 personnel) spread offenses. Then more tight ends who could catch the ball declared for the draft right as NFL secondaries got smaller and faster as teams opted for more defensive backs on the field to counter the number of receivers they had to defend. Putting a 6-foot-5 and 250-pound “receiver” in the slot against a nickel cornerback is a significant advantage, as is scheming that player against a linebacker in coverage. (As a reaction to this, teams are starting to play bigger safeties as their nickel defenders instead of smaller cornerbacks.)

With defenses generally built to counter 11 personnel, teams have increased their usage of 12 personnel (two tight ends, two receivers, one running back). In 2024, teams played in 12 personnel at a 22.1 percent rate — the highest since 2017 — and in 2025 they are in 12 personnel even more often (23.9 percent of snaps). Between 2017 and 2023, no more than 15 NFL teams used 12 personnel on 20 percent or more of their offensive snaps in any one season; 2024 featured 18 teams that did and 2025 so far features 20.

The heavier personnel helps in the run game, where the NFL has also enjoyed a small renaissance over the last two seasons. It’s simple: A higher number of larger, physical players are available to block for the running back. If an offensive coordinator also passes the ball frequently out of 12 personnel, he can disguise whether the play will be a run or a pass and still keep a size advantage.

Some teams have multiple tight ends who are capable in both the run and pass game. Teams like the Washington Commanders clearly favor one player as the pass catcher but have invested into the position overall to build a balanced room. The Commanders paired veteran Zach Ertz, who is especially a threat in the passing game, with a teammate in 12 personnel who is a better run blocker in John Bates. An offense that wants to be in 12 personnel as often as the Commanders do (on about 24 percent of offensive snaps since the start of last season) had to build a tight ends room where players weren’t just carbon copies, but had above-average traits in areas that complemented one another.

“I think if you become too much like ‘these guys are both pass game guys’ … then (defenses) can definitely play different packages and change it up and treat it more like a pass set. But with Bates and (Ertz), we’ve been able to get a lot of nickel, which has actually helped us,” said Commanders offensive coordinator Kliff Kingsbury.

Similarly, the Arizona Cardinals have paired top pass-catching tight end Trey McBride — who accounted for almost a third of the team’s targets in 2024 and was eighth in the NFL in targets among all players — with blocking tight ends who aren’t liabilities in the passing game such as Tip Reiman or Elijah Higgins (also a converted receiver). Arizona played 12 personnel on almost 30 percent of its snaps in 2024 and led the NFL in 13 personnel (three tight ends, one receiver, one running back). The Kansas City Chiefs understand they have an All-Pro passing game mismatch in Kelce, but they also play No. 2 tight end Noah Gray 40-plus percent of snaps and are in 12 personnel over 30 percent of the time.

“Noah Gray does a great job with all the blocking stuff, and because there is two tight ends in the game — if you go nickel (defense) against that to try to cover Travis, ‘All right we’re just gonna run the ball, it is what it is, good for you guys,’” said Kittle. “Or if they put a linebacker out there (instead), they’re gonna spread them out and use Noah in protection and let Travis go run routes on a linebacker or strong safety, who can’t cover him. Those are mismatches that having two really good tight ends does for you. It opens up so much offense.”

The increasing number of offenses that want to play in 12 personnel need to have tight ends who might excel in one area but can be above-average in both phases of the offense. For young tight ends especially, the biggest learning curve out of college is understanding how to block in the NFL.

That’s where Paulsen comes in.

Ferguson and Kittle agreed that Paulsen is a tight end “librarian.” Like many of his colleagues at the position, he is a keeper of its lore.

“He really loves the game, he loves teaching, he loves the little nuance to football,” said Ferguson. Even as a player, it was Paulsen’s gift.

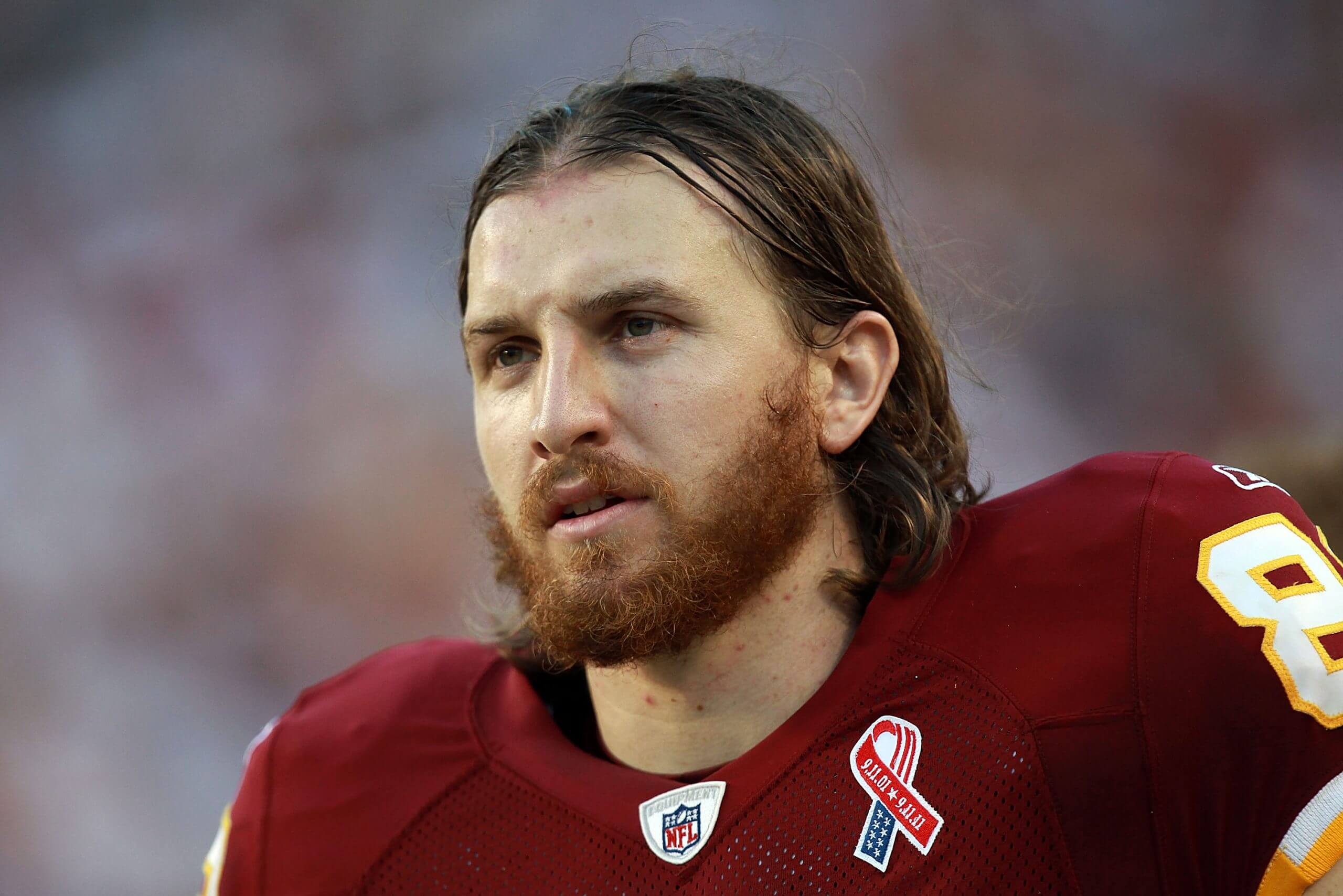

From 2010 to 2019, Paulsen played for Washington (he now is an analyst for the team’s broadcast partners), Chicago, San Francisco, Atlanta and Houston. He became known especially among the coaches who developed in the Mike Shanahan coaching tree as a guy they could go to for information and insight. Shanahan, the head coach in Washington from 2010 to 2013, once grilled Paulsen on offensive tackle protections out of worry the tight end might have to play emergency tackle in a preseason game. Paulsen answered every one of Shanahan’s questions correctly, then rattled off the assignments for the guards and center, too.

Logan Paulsen’s NFL journey began as an undrafted free agent with the Washington Commanders. (Ronald Martinez / Getty Images)

After that, Shanahan said Paulsen would always have a roster spot on any team where he was a coach. And after Paulsen’s five seasons in Washington, several of those Shanahan-tree coaches indeed shuffled Paulsen from building to building, staff to staff. In San Francisco in 2017, he and teammate Garrett Celek mentored the rookie fifth-rounder Kittle.

“I was so lucky,” said Kittle. “I knew (Garrett) as my big brother, and Logan would be our dad. … One thing I took from (Logan) was his second-level blocking mindset. He called it ‘the gallop’, which is when you are going through the defensive linemen to go block a linebacker or safety, to drop your hips and kind of gallop so you don’t cross your feet over. … No one had ever talked to me about that. Hearing him explain why we were doing it, it made so much sense, and it completely changed my mindset of blocking. I still do all of that stuff today.”

In Atlanta in 2018, young tight end Austin Hooper learned that Paulsen was also doing scouting reports on tight ends who were upcoming draft prospects for the staff and for his agent.

“Unbeknownst to me, he was one of the guys who gave a positive scouting report on me coming out of Stanford,” said Hooper. “He was a true student of the game. He was the one who really harped on not just knowing what you’re doing but what the linemen around you are doing, what the receivers around you are doing; what the defense is doing, what their rules are and if you can manipulate a defender pre-snap. … It really opened my eyes to that side of the game.”

For Paulsen, explaining what he saw and how things worked was a simple courtesy and all he’d known as a tight end. “I had all of this information. So let’s talk about it. Let’s pass it along.”

Paulsen broke down mountains of film for teammates behind the scenes but was never in a featured role himself. He was generally a No. 2 or 3 tight end — the blocking player digging out the dirty work in the run game, or helping to set up the No. 1 tight end in the passing game. He initially made Washington’s roster as an undrafted free agent out of UCLA. Beyond his rookie contract, he had just one multiyear deal. After he was cut by Washington in 2016, he asked himself what he really wanted out of his career and realized it was to see if he could play 10 years.

“Kinda clawed, scratched, begged and borrowed and made 10,” he said. “Did it meet expectations? I didn’t have any, initially. I was playing with house money for a while. Then I got good, then I got disappointed. I got humbled. And I felt like I finished on a decent high note in Atlanta (in 2018-19). … Looking back on it, it’s pretty cool. People don’t get to ride that train for a long time.”

In retirement, Paulsen does a little bit of everything. He consults, he serves as a broadcaster and an analyst for Commanders-affiliated programs, he coaches youth football, he has developed exercise equipment and athletic training programs, and he works with Caric and the young tight ends. The pull of the NFL is strong, and might eventually reel him back onto a coaching staff somewhere.

“He’s got a number of opportunities, if he wanted them, to be a coach,” Hooper said.

Logan Paulsen, right, helped develop Austin Hooper early in his NFL career. (Kevin C. Cox / Getty Images)

But Paulsen has held that life at arm’s length. For a decade, NFL Sundays ruled his life and dictated his emotional and physical well-being.

“Like, I still have dreams about getting cut from football teams,” he said. “(Near) football season, I’ll wake up in a sweat that I’m late or that I don’t know a play. F—, it’s been like six years, you know?

“… I cannot have my life governed by Sundays anymore. I cannot be happy or sad depending on whether we win this game. … This is a little bit safer. We can learn, we can talk, we can coach. I’m invested in the guys I coach. But there’s no Sunday.”

There is an organic, honest feeling to Paulsen’s training. Players who get sent to him are provided housing by their agent for their stay, but sometimes they just end up sleeping on his couch. It’s big enough for a couple of 6-foot-5 tight ends and the dogs to sprawl out during the hours of film study. The living room walls in Paulsen’s home are covered in framed photos of Kelly and their kids. Players often tag along to the kids’ hockey and basketball games between training sessions. There are notebooks covered in Paulsen’s thin scrawl and play drawings everywhere. One of his dogs rolls up on his leg as he goes through film. Paulsen flips through cut-ups and points out spacing and the tiniest of movements in a route, the angles of hips and feet and placement of hands in a block. He notes how route-running doesn’t have to be rigid just because it’s mathematical; Kelce, for example, is “painting” with his movements instead of solving an equation.

At TEU, attendees arrive at the event to cameras, sponsors and swag bags full of goodies. At Paulsen’s house, players walk past a minivan in the driveway, ring the doorbell and listen for a moment as Paulsen and Kelly corral the dogs and the kids. Kelly always warmly invites them to stay for dinner after film or their workout.

It’s a little less “TEU,” more “TE2.” Both reflect and honor the evolving identity of the position, just in different ways.

Paulsen laughs good-naturedly at the turn of phrase. He was “TE2” as a player, and still is as a teacher. There are always the guys in the light, and the guys on the back side of blocks. They all matter. Football goes through its cycles. The lore of the position is passed on.