CARNELIAN BAY, Calif. — Before a 10-mile run on a cool sunny morning six years ago, Robert Gallery pulled on calf sleeves and compression pants to help with the soreness. The former offensive lineman still weighed 285 pounds, and training for a half-marathon was hell. No matter, he needed to run because it helped clear his head, as much as a head like his could be cleared.

Gallery came to the crosswalk on Highway 89, which borders Lake Tahoe and runs toward Emerald Bay. The street was busy with construction traffic, school buses and 9-to-5ers sipping lattes and checking their hair in rearview mirrors. As he waited for a break, a semi-truck came barreling through.

That’s when the thought hit him.

What if I step in front of the semi? I’ll be killed, and it will look like an accident. No one will think I’m a coward.

Suicide — or more accurately, making the noise stop — had been on his mind.

Gallery courted death, riding his motorcycle 90 miles an hour in a 35-mile zone, weaving around cars and trucks. He floored it in his EV — up to 120 — hugging curbs and screeching tires. High in the Sierra Nevadas, he went off-road on his dirt bike and steered closer to the edges than any mountain goat would go.

It didn’t seem that long ago when he won the 2003 Outland Trophy as the top interior lineman in college football. Joe Bugel, a foremost authority on offensive line play and the coach of Washington’s Hogs, predicted Gallery would be a 15-year Pro Bowler.

After the Oakland Raiders made him the second pick of the draft, Gallery didn’t make any Pro Bowls.

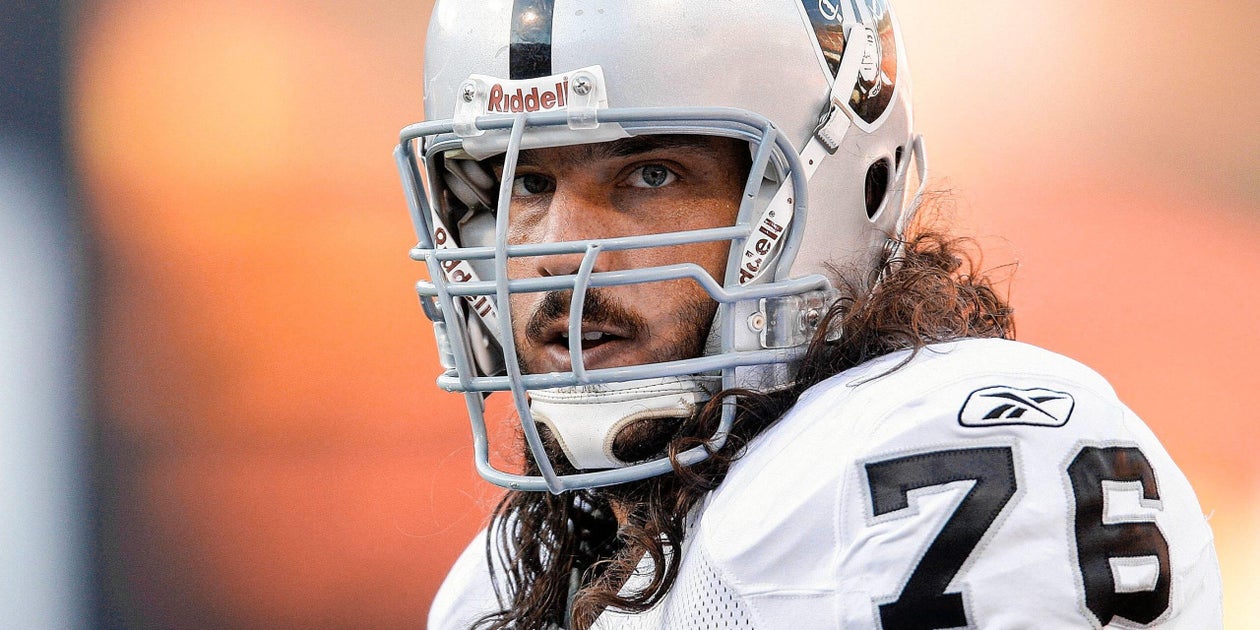

But that didn’t make him any less of a badass. With shoulder-length hair, a lumberjack beard and tattoos that wallpapered his torso and arms, Gallery, who stood 6 feet 7, weighed 325 pounds, ran the 40-yard dash in 4.98 seconds and bench-pressed 225 pounds 32 times, dealt in intimidation.

He lasted through 10 surgeries and eight NFL seasons until he had nothing left. Regretfully, he retired, harrowed by what could have been, should have been. Then came the brain fog, ringing in his ears, memory voids, tequila, rage and thoughts of taking his life.

At the crosswalk on his run that morning, Gallery took a deep breath, let the semi pass and started to jog.

All that mattered was making the noise stop.

As a 5-year-old, he was assigned to pick up rocks and toss them in a wagon on 400 acres that had been passed down from one generation of Gallerys to another and another. As he grew, Gallery graduated to more challenging tasks — driving the tractor, tilling the land, baling hay and unloading corn and soybeans into augers that led to a storage bin.

The farm was outside of Masonville, a town in Eastern Iowa with a fish fry/bar, a church, a grain elevator and not much else. For his Eagle Scout project, Gallery built flower boxes for the local park. The locals still talk about it.

An eight-mile drive on a gravel road took him to East Buchanan High, where Gallery would become president of his class and a member of the National Honor Society. They came from miles around on Friday nights to watch his team play on a football field illuminated by the floodlights of neighboring farms. As one of 18 players on the team, he lined up at tight end, defensive end, linebacker, kicker and on all special teams. He also played basketball, participated in high jump and was a member of the 4×100 relay team.

Gallery was recruited by Iowa as an athlete, meaning nobody was sure what he could be.

Or couldn’t be.

In the first four games of his freshman season, Gallery played tight end. Three days after the fourth game, he was moved to offensive tackle and four days later started as an offensive lineman for the first time in his life. He was a natural, raw but resolute.

While teammates relaxed in a hotel ballroom the night before a game, Gallery quietly slipped out and, by himself in a secluded corner, went through his steps, over and over. Later, when he couldn’t sleep, he slinked into the bathroom of his hotel room so his roommate wouldn’t be disturbed and practiced hand placement in front of the mirror.

The routines became part of his game preparation for as long as he played.

During Gallery’s junior year, the Hawkeyes finished 11-2, Gallery was voted first-team All-Big Ten, and football never was more gratifying. By then, teammates were calling him “The Mountain.”

Robert Gallery’s future appeared bright when he played at Iowa under coach Kirk Ferentz. (A. Messerschmidt / Getty Images)

After that season, Iowa coach Kirk Ferentz told Gallery he could go pro and be a top-10 draft pick. Gallery said his coach’s words were “flabbergasting.” All he ever thought about was his steps, hand placement and being better on the next play and the next game.

Gallery decided to stay for his senior season, but everything changed after that conversation.

“I felt I had to be perfect every single play,” he says. “It took a little of the fun away because I was so worried about it.”

Nonetheless, Gallery improved to the point that he was compared to future Hall of Famers Tony Boselli and Orlando Pace. Former Iowa strength coach Chris Doyle says Gallery was “arguably the best offensive lineman who ever played college football.”

After the season, Gallery was in an airport when he saw a copy of The Sporting News on a magazine rack with Eli Manning, Larry Fitzgerald and Gallery on the cover.

“Here I am, this small-town kid from Iowa buying a magazine with a picture of me on the cover,” he says. “I still have it somewhere in a box.”

He grew his hair in college because his mother wasn’t around to give him a fresh cut and he didn’t want to pay a barber. By the time Gallery was drafted by the Raiders in 2004, he hadn’t had a haircut in 2 1/2 years.

His look was part of his persona. His style was old school.

During one game, Gallery had to urinate. Rather than run back to the locker room, he went in his uniform pants. It became his thing, and he did it every game, pointing out what he was doing to opponents as he did it. He wiped his hands on his wet pants when they were looking at him, then put those hands on their jerseys.

“I was sick-minded and I loved the mental warfare,” he says.

He also loved the physical warfare.

“He was a grinder, a tough guy who liked to get after it and was not afraid to put his head in there,” says Hall of Fame defensive end Jared Allen, who had many battles with Gallery. “You knew he was going to block a few seconds after the play.”

Gallery reveled in blasting unsuspecting defensive backs in the open field and delivering since-outlawed chop blocks that snuffed the fire in pass rushers. When he played guard, he told the tackle next to him to overset, an invitation for the defensive end to come inside. Gallery would be waiting, ready to use his 22-inch neck and head to strike like a cape buffalo.

“At the time, I was seeing stars, but I was making this guy see stars, too,” he says. “And I know he’s not going to want to do this play after play after play.”

Gallery kept a facemask with a bar that is bent inwards and cracked, a trophy worth a thousand words.

He would have been the quintessential Raider if only he had been born three decades earlier and played for John Madden and blocked for Ken Stabler. But these Raiders weren’t those Raiders — these were the Raiders of Al Davis in the gloaming, whose motto should have been “Just Can’t Win, Baby.”

In seven years with the Raiders, Gallery had five head coaches, played in six offenses, blocked for a dozen starting quarterbacks, lost 70 percent of his games and never made the playoffs.

In his first two years in Oakland, he started at right tackle, then moved to left tackle in his third year. That season, the Raiders brought Art Shell out of retirement to be the head coach and hired an offensive coordinator who hadn’t coached in the league in 12 years and had been managing a bed and breakfast. Jackie Slater had been one of the all-time great offensive tackles but was a green coach in charge of the offensive line. He coached vertical pass sets, which were foreign to Gallery. During a 2-14 season, Gallery was one of many Raiders who struggled.

Gallery turned on NFL Network on one of those hard days. Former player Jamie Dukes was ripping the Raiders. Then someone brought up Gallery. “He’s a bust,” Dukes said.

In his fourth season, with Tom Cable as his new position coach, Gallery was moved to left guard, where he played the rest of his career. He resisted the change initially but grew to appreciate the mauling aspect of interior line play.

Cable eventually became head coach of the Raiders but was fired after the 2010 season. He went to Seattle as offensive line coach, and Gallery, upon becoming a free agent, followed him. On the ground floor of Pete Carroll’s ascendant program, Gallery shared a locker room with Marshawn Lynch and the Legion of Boomers and finally saw pro football done right. It was rejuvenating.

But by then, the 30-year-old was breaking down physically. At times, his vision was off. He walked to the line on occasion, unsure of the play that had just been called. In training camp, he had pain in his abdomen but played on. He tore his MCL in the final preseason game, had hernia issues all season and played five games with a completely torn abdominal muscle.

The day before the season’s last game, he could barely walk from his bed to the bathroom. He sat in a steaming hot bath in a Chicago hotel room for a long time, thinking. “How am I going to play tomorrow?”

He found a way but didn’t perform as he hoped and soon was cut. He had surgery on his abdomen and elbow and signed with the Patriots. A couple of weeks into the next training camp, he admitted he couldn’t do it anymore.

He retired, feeling like a quitter.

Gallery had been a football soldier as much as a player, marching in cadence to his team’s routines, processes and calendars. Though his career hadn’t gone the way he hoped, it defined him. If he wasn’t a football player, who was he?

From his couch, he watched an NFL playoff game, the kind he never had a chance to play in. He became angry, unreasonably angry. He took it out on his wife, Becca, and three children. The kids’ giggles made him see red. “Everybody shut the f— up!” he yelled.

Increasingly, he was irritated and agitated. Sometimes, everything light became dark in a flash. An iPad was destroyed. There were shattered dishes and glasses, and a hole in a whiteboard from his foot. Behind the wheel, he felt pulses of rage and the urge to reach inside his console vault for his handgun. He had to remove the temptation.

He and his wife say he was never physically abusive to her or their children. “That’s just not in him,” she says. But the sinister truth is he felt urges that made him ashamed.

“Wanting to hurt someone, that’s a terrible feeling,” he says. “You feel like the worst scum on the face of the earth that you would want to hurt your children or wife. And that messed with me even more.”

Gallery wondered if he was bipolar or losing his mind. His thinking always seemed clouded and impeded by tinnitus. There were times he couldn’t remember his children’s names. When he was driving familiar roads, he sometimes became disoriented and had to look at a map or call Becca to ask her where he was headed.

He detested attending his kids’ school and sports functions because he had to interact with people. Gallery found a way to numb his anxiety, bringing a bottle of tequila and emptying it one double on the rocks at a time. If he were ordering from a bar, he might down 10 doubles in an hour.

Becca made up excuses so her husband could stay home. For a long time, she felt like a single mom, carrying all the burdens.

Old friends and teammates texted and called. For about 10 years, Gallery didn’t answer. “He just kind of went dark,” says Erik Jensen, his college roommate and teammate and one of his best friends.

Fearing Becca would leave him, Gallery didn’t share most of what he was feeling with his wife. He regularly spoke with Doyle, however. “He was,” Doyle says, “in a dangerous place.”

Suicidal ideations and dreams became more common. During a bout of COVID-19, Gallery dreamt that the metallic taste in his mouth was from a gun barrel. He arose another time with his heart racing and one hand fighting with the other after dreaming he was pointing a pistol at his head.

A turning point for Robert Gallery came when he asked his wife, Becca, for help. (Dan Pompei / The Athletic)

He and Becca work out together. They were taking turns sprinting in their driveway one morning, and it was his turn to go, but instead, he walked in circles, looking disturbed. She asked what was wrong. He broke down and asked for help, using words he never had before — depression, anxiety, burden, suicide.

His admission was a relief for Becca because she knew. Wives always know. She told her husband he needed to speak with someone who understood what he was feeling.

The music of Metallica always resonated with Gallery. During his rookie season, he ran into Metallica lead singer James Hetfield at the Oakland San Francisco Bay Airport. Gallery introduced himself and they became friends, eventually getting to know one another’s families. After his confession to Becca, Gallery contacted Hetfield, who had struggled with depression, anxiety and alcohol abuse. Hetfield, in a series of deep conversations, shared how he healed and helped Gallery understand that his family needed him even if he was imperfect.

Gallery was ready to try anything. Therapy wasn’t doing it. He had a SPECT scan taken that showed his brain appeared mangled. He curtailed drinking, addressed an imbalance in hormones, used a hyperbaric chamber and had fusion and IV therapy. Sleep subsequently improved, but depression did not.

About four years ago, Gallery started listening to “Team Never Quit,” a podcast with Marcus Luttrell, the only surviving Navy SEAL from a 2005 mission in Afghanistan and subject of the motion picture “Lone Survivor.” One of Luttrell’s guests was Marcus Capone, another former SEAL. In their conversation, Capone talked about his depression. All his symptoms were Gallery’s symptoms.

Ibogaine is a psychedelic made from a shrub that has long been a part of ceremonies and rituals in some African tribes. It also has been used to treat brain injuries, post-traumatic stress, substance dependency and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis and ALS. It is illegal in the United States, but Texas has approved $50 million for clinical trials. The drug lengthens the time between heartbeats and could result in cardiac complications.

On “Team Never Quit,” Capone testified that Ibogaine saved his life.

Gallery contacted Capone’s VETS foundation, which helps struggling veterans with mental health issues. Capone and his wife, Amber, told Gallery their foundation had sent more than 200 people for Ibogaine treatment.

The solution may have seemed radical, but desperation doesn’t tolerate hesitation, so Gallery signed up immediately, stopped taking antidepressants cold turkey and was on his way to Mexico in three weeks. “I had to believe it could work because I thought it was my last chance,” he says.

Upon arriving at The Mission Within in Tijuana, Gallery and four others, including Luttrell, received medical clearance, then participated in a fire ceremony. He wrote what was hurting him on a piece of paper.

I want to get rid of my rage. I want to love myself. I want my family to love me. They hate me because of the way I act.

Gallery threw the paper into the fire.

He ingested the Ibogaine capsule and reclined on a mattress on the floor. It felt as if he melted into the ground. Then it was as if he were drifting in space with lights and stars flying by. And then there were television screens, each one retelling an episode of his life, from living on the farm to meeting Becca on her first day on the Iowa campus as a member of the basketball team to the 2-14 season.

After not moving for 12 hours, Gallery woke up feeling so sick that he hoped to die. When he tried to stand to go to the bathroom, he couldn’t. His legs didn’t work.

The next day, Gallery felt well enough to smoke 5-MeO-DMT, a psychedelic from the venom of Sonoran Desert toads. After inhaling, he experienced an ego death.

“I’m out of my body and I went to the white light, and then my God appeared,” he says. “I started screaming at him, telling him I was a failure and a terrible husband and father. I told him to send me to hell.”

God refuted him, and at some point, Gallery felt a weight lifted. He thought about all he accomplished and the good he had done for his wife and family.

As the 5-MeO-DMT wore off, he was blissful. There was no ringing in his ears and he could think cogently. Ocean waves slapped the shore about a mile away. He heard them as if they were playing on noise-canceling headphones. The sweetness of fruits exploded in his mouth.

“The sensations of everything were so intense,” Gallery says. “And it was the first time in years that there was nothing negative going on in my head. I was just there with nothing to worry about, feeling freedom.”

He flung open the door to a room where the others were.

“I’m back, b——!” he said.

It was evident in his aquamarine eyes. “Before then, they were dead, no life in them, no color,” Becca says. “Now they are bright, glossy eyes, full of joy.

In the coming months, Becca found her husband to be like “college Robert.” He was carefree, tolerant, in control, compassionate, gentle, present and capable of helping her with parenting and managing the house.

About one year after his treatment, Gallery started feeling uneasy again. He and Becca were building a dream house with a cavernous garage. He walked into it and envisioned hanging himself from one of the beams.

In 2023, he returned to Mexico, this time to Ambio Life Sciences, for another round of Ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT.

Robert Gallery (far right) went to Mexico for his first treatment with (from left) former Navy SEAL John Jones, former Air Force Tactical Air Control Patrol Specialist Jarred Taylor, former Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell and former Navy TOPGUN Fighter Pilot Matthew “Whiz” Buckley. (Courtesy of Robert Gallery)

The tattoos on Gallery’s right leg are vivid. There’s a motorcycle on fire, a Hannya mask, a Japanese demon, a chained tiger and the acronym FTW, for “F— The World.”

He had those images tattooed during his worst days.

His left leg was inked after Ibogaine. There’s his mother, his father, Jesus, the Virgin Mary, roses and a sacred heart.

His latest tattoo is on his neck. It’s a skull, representing the death he experienced.

But it has wings.

Now 45, Gallery thinks about how he got here. He goes back to his NFL career, or it comes back to him.

“It still haunts me,” he says. “I had expectations for what would happen, but for whatever reason, that wasn’t my story to have. I loved playing the game, but do I think about that at night, 15 years later? Absolutely.”

For a long time, the bent-bar facemask was on display in his home with game balls, trophies, jerseys and helmets — a source of pride. Now the facemask is in a storage bin. “The meaning kind of changed for me post-medicine,” he says.

Football was so important to him. But his more recent battles have much higher stakes.

Since his second Ibogaine experience, Gallery has had no macabre thoughts or angry outbursts. His ears don’t ring and he’s clear-headed most days. He still gets a little anxious at times, but who doesn’t? His last drink was four years ago.

A follow-up SPECT scan about a year ago showed his brain doesn’t look much different, but scans don’t reveal everything.

“I’m not healed from Ibogaine,” he says. “The reality is I have brain damage. But it drastically helped me. I’m light-years ahead of where I was.”

He opens his eyes every morning at 3:58, just before the 4:00 alarm. He goes from the warmth of his bed to a 35-degree cold tub, and then it’s meditation and breathwork. At 5, he and Becca begin a 90-minute workout. After helping get the kids to school, Gallery spends an hour in his hyperbaric chamber. Later in the day, he and Becca go wake surfing on Lake Tahoe.

He doesn’t do these things because he likes to. He does them because he needs to.

He also needs to help others like him. “I think that he sees that as his responsibility to kind of be a lighthouse,” Doyle says.

Earlier this year, Gallery founded Athletes For Care, which offers retired athletes mental health resources and assistance with psychedelics.

At an Iowa football reunion, he saw old friends for the first time in years. He apologized for disappearing and explained that he felt like he was in a new place. It was of particular interest to Jensen, who spent time with five NFL teams over four seasons and went weeks at a time during training camps with a throbbing head. All those years later, Jensen was often angry without reason.

After a series of conversations, Gallery accompanied Jensen to Mexico for an Ibogaine treatment. Jensen describes the experience as “life-changing” and says his emotions have stabilized.

Jensen is one of 10 people who have taken Ibogaine because of Gallery.

After Gallery was back to being himself, he recommitted to running the half-marathon. He wanted to do it in honor of a friend who was depressed and killed himself. Becca joined him. His goal was to run the 13.1 miles without stopping, but about halfway through, his legs cramped. He ran/walked for a time and told Becca to continue without him. She refused, staying by his side as always.

If Gallery had been unable to finish a race during his years in crisis, he would have grown stormy. He would have lashed out.

At one point, as he and Becca slowly made their way toward the finish line where their children were waiting, he became emotional.

But not like before.

“I’m alive!” he yelled, his eyes glistening. “I’m alive!”

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 for the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.