After more than a century acting as a climate buffer, the Southern Ocean may be preparing to release a vast store of heat, sending global temperatures rising again, even after humanity curbs emissions. This unexpected thermal release, described by scientists as an oceanic “burp,” could keep warming alive for over a hundred years. According to new modeling published in AGU Advances, the heat stored deep in the Southern Ocean could emerge centuries after global cooling begins.

Ocean Heat Could Restart Climate Crisis

For decades, the Southern Ocean has absorbed about 25% of CO₂ emissions from human activity, along with over 90% of excess heat, according to Phys.org. This has delayed some of the worst impacts of climate change. However, new simulations suggest a hidden consequence: deep ocean layers, saturated with heat, may release it abruptly in the future, even when emissions are reversed and temperatures fall.

The result could be a renewed pulse of warming from the maritime zone, without any new CO₂ entering the atmosphere. The research published on October 15, 2025, led by Ivy Frenger from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, used the UVic Earth System Climate Model to simulate a future where carbon emissions rise for 70 years, then rapidly decline, followed by sustained net-negative emissions.

Heat Out of Time

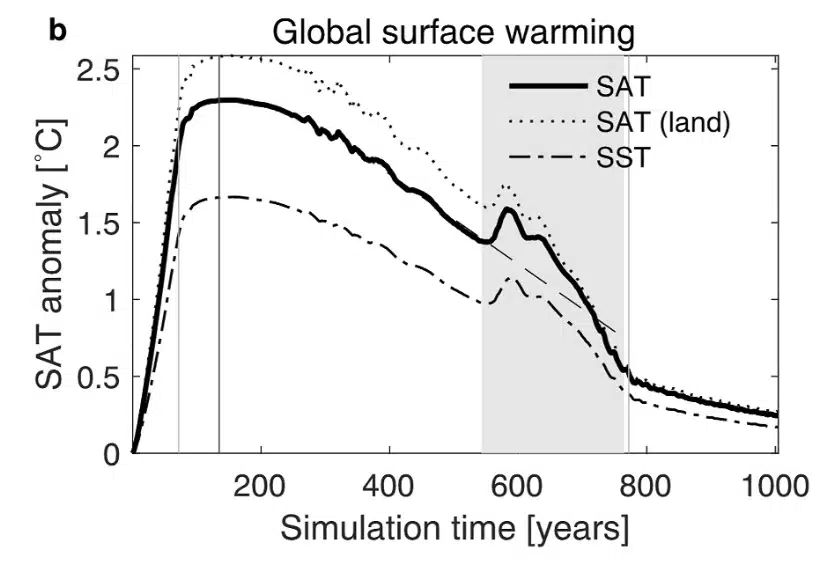

What makes this scenario particularly striking is the lag between cooling and heat release. The thermal surge happens centuries after global temperatures begin to decline, and is not a gradual process but an abrupt release of stored energy, a true climatic recoil.

This warming could last for decades to centuries, at rates comparable to the average pace of anthropogenic global warming. While some CO₂ is released, the primary impact is thermal, not chemical. In other words, the atmosphere warms due to long-held ocean heat rising to the surface, not fresh emissions.

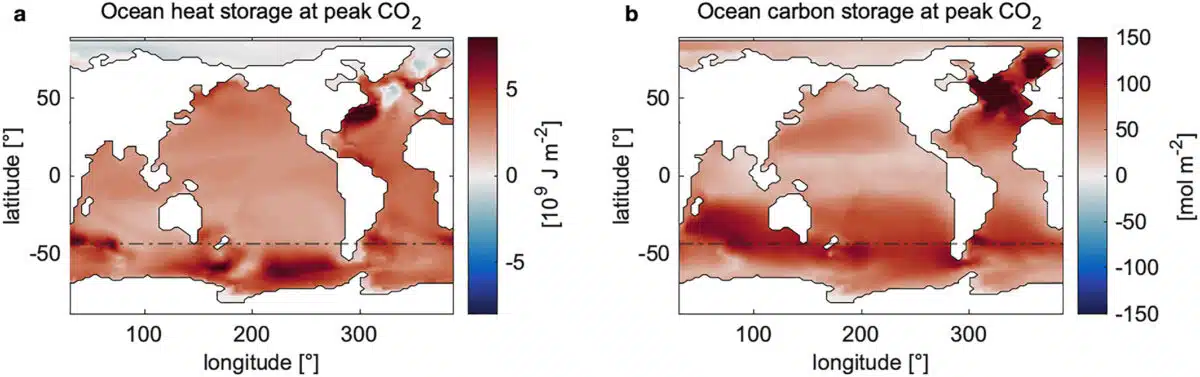

Ocean heat (a) and carbon storage (b) at peak CO₂ levels, showing spatial distribution. Credit: AGU Advances

Ocean heat (a) and carbon storage (b) at peak CO₂ levels, showing spatial distribution. Credit: AGU Advances

Sea Ice Loss Sets the Stage

A critical factor in the Southern Ocean’s transformation is the loss of sea ice, which normally reflects solar energy back into space. As emissions rise and polar ice melts, the ocean absorbs more shortwave radiation. This shift in surface reflectivity (albedo) allows the deep-sea to store more heat.

As ScienceAlert reports, two processes contribute: warmer surface waters mix with cooler layers, ventilating heat into the depths; and the ocean’s natural heat release pathways become less active. These combined effects trap heat where it cannot easily escape, setting the stage for a delayed warming rebound.

The values are shown as deviations from preindustrial conditions, with the ‘burp’ marked by gray shading. Credit: AGU Advances

The values are shown as deviations from preindustrial conditions, with the ‘burp’ marked by gray shading. Credit: AGU Advances

Unequal Impacts on the Global South

Although the thermal “burp” is a global phenomenon, its effects are not evenly distributed. The researchers found that the Southern Hemisphere bears the brunt of the warming, with longer-lasting and more intense impacts than the north. This is partly due to oceanic circulation patterns and the region’s proximity to the heat release.

The same source noted that this creates a concerning future for the Global South, where climate vulnerability is already high. Countries in this region may face renewed environmental stress, even after global emissions have declined. This challenges assumptions about the speed and equity of climate recovery.

If oceans continue to warm the planet long after we cut emissions, current targets and models may be overly optimistic about the timeline for results.