Touring the West during the height of the COVID pandemic, Courtney Buchanan lived out of her truck, slept wherever she ended up and lived off propone-stove-cooked meals.

The then-University of Wyoming researcher was a nomad with a purpose, combing Western rangelands for free-roaming horses and the dung they left behind in search of clues about what they were eating and how they were faring. During surveys across seven Western states, she was struck by how the animals were consistently in good shape. She found the fattest horses in the Bighorn Basin, not far from home.

“The McCullough Peaks horses were in the best condition out of any of the horses I visited,” Buchanan told WyoFile. “It was wild to me, being out on the range, seeing them. Some of them are actually overweight — fat, chunky horses.”

Horse manure. (Courtney Buchanan)

Horse manure. (Courtney Buchanan)

The findings of Buchanan’s recently completed study help explain why. The University of Wyoming Ph.D. graduate examined the composition of horses’ diet, how much it varied by season, and how much it varied from one reach of the equines’ Western range to another. She found great variation on all fronts.

“Our big takeaway was that in different environments and different places and in different seasons, they can really switch up what they’re doing and still be successful,” Buchanan said. “If they’re able to vary their diet that much and still maintain body condition, that sets them up for success.”

The dietary flexibility, she said, could help explain why rangewide free-roaming horse and burro populations are “so high” — at roughly 73,000, they number nearly three times land managers’ goal.

Buchanan studied under UW ecology professor Jeff Beck, who’s researched free-roaming horses for a decade, including how the large herbivores are negatively influencing sage grouse survival rates.

The study on diet and body condition, which looked at 16 herds in seven states, was recently published in the journal of Rangeland Ecology and Management. In their concluding remarks, Buchanan and Beck suggested that range managers could use their findings to help strike a balance between free-roaming horses, livestock and wildlife.

“While studies in individual locations and a meta-analysis of western North America have indicated low potential for direct dietary competition with free-roaming horses and wild ungulates that consume woody species such as mule deer and pronghorn, our findings indicate that there may be more potential for dietary overlap and competition during winter,” they wrote.

Going into the study, the ecologists sought to test the common view that horses are true grazers. Old research from the 1970s had found that horses in most herds ate predominantly grass, Buchanan said, though there were some exceptions and herds that also concentrated on other plant families.

Horses from the Adobe Town Herd in the winter of 2020-21. (Courtney Buchanan)

Horses from the Adobe Town Herd in the winter of 2020-21. (Courtney Buchanan)

In the lab a half century later, Wyoming researchers tested the horse manure Buchanan collected using a technology called DNA metabarcoding. That technique narrowed the contents of the feces down to the plant family level, though results weren’t accurate enough to reliably predict the species, Beck said.

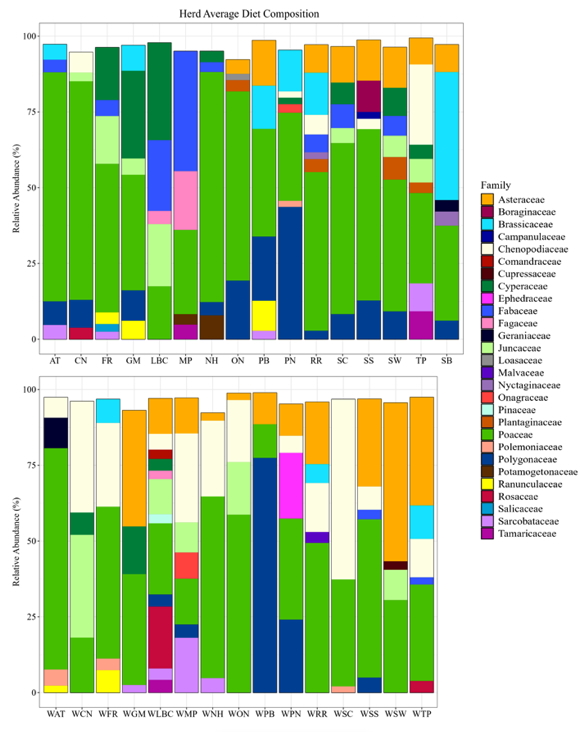

Buchanan found that some herds fit the horses-are-grazers reputation. For example, the Adobe Town Herd — part of the historic “checkerboard” horse dispute — ate predominantly Poacae, the grass family, regardless of the season. But diets varied wildly and, in many places, grasses were less than half of horse diets, especially in the winter.

“Each herd’s kind of doing a different thing,” Buchanan said.

What wild horses eat varies dramatically, both seasonally and across their range, as illustrated in this graph of 16 herds’ diet composition. Summer is up top, winter is down low and the scientific names of plant families are on the legend at right. (Rangeland Ecology and Management)

What wild horses eat varies dramatically, both seasonally and across their range, as illustrated in this graph of 16 herds’ diet composition. Summer is up top, winter is down low and the scientific names of plant families are on the legend at right. (Rangeland Ecology and Management)

The plump McCullough Peaks horses, for example, homed in on legumes in the summer, but come winter switched to eating more from the Chenopodiaceae family — spinach-adjacent plants — than anything else.

The most slender horses that Buchanan encountered were in southern Utah’s North Hills Herd. There, animals ate mostly species from the grass family in the summer and winter, the study shows.

One limitation of the research, Buchanan said, was that the manure was collected over the course of a few days in any given herd. Findings about diet, in other words, are a snapshot in time.

Regardless, that doesn’t detract from the UW researchers’ overall finding: “They’re eating lots of different stuff,” Buchanan said, “but staying in pretty good condition.”