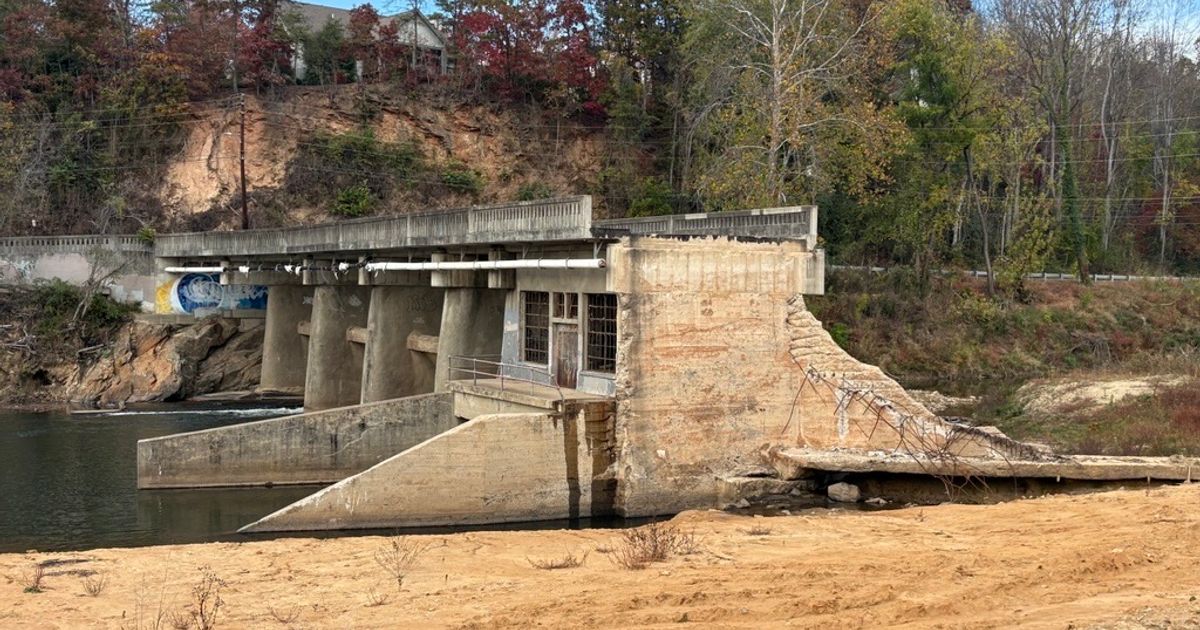

The cracked concrete at Lake Craig Dam still bears the scars of the storm.

Chunks of the bridge above are missing, ripped away when swollen floodwater pushed past the aging structure, carrying tree limbs, sediment and debris until the river carved its own escape route.

“We would be very underwater right now,” said Erin McCombs, Southeast conservation director for American Rivers, standing beside the breach. She lives just downstream. When Hurricane Helene roared through last fall, gauges failed under the pressure. “The Gage was so overwhelmed that it went offline,” she said. “We can’t even fully measure what happened here.”

State engineers say Helene damaged or destroyed more than 40 dams in September 2024 across North Carolina, many of them decades beyond their intended lifespan. The failures forced a reckoning: as storms grow stronger, the state’s thousands of aging, privately-owned dams are becoming a dangerous liability.

A quiet removal that saved a community

On the Watauga River, about two hours northeast of Asheville, a different story unfolded.

“The flood would have crested 12 to 15 feet higher if that dam had still been there,” said Jon Council, who lives in Sugar Grove. The 19th-century dam upstream from his neighborhood was removed with state and federal support a few years before Helene.

“It would have backed water into homes upstream and then, when it failed, sent a surge downstream,” Council said. “Removing it prevented millions of dollars in damage and probably saved lives.”

The dam, once used for power and milling, had fallen into disrepair. Fixing it would have cost four times as much as removal, according to state assessments. And like most dams in the state, it was privately owned, leaving costly maintenance to landowners.

“People don’t realize how much of this responsibility falls on private property owners,” Council said. “Most of these dams don’t protect against flooding. They actually raise water levels behind them.”

A first step, not a finish line

After Helene, state lawmakers created a $10 million Dam Safety Grant Fund to repair or remove damaged dams, part of a larger disaster relief package signed by Gov. Josh Stein.

Advocates call it a start, not a solution.

“The average dam removal is about $1 million,” McCombs said. “We had more than 40 high-hazard dams impacted. This is a down payment, but not the scale of investment resilience really requires.”

Council agreed, adding that emergency spending will only multiply without a permanent funding stream.

“We shouldn’t be in a position where we pick which communities get protected first,” he said. “Climate disasters aren’t one-off events anymore.”

Built for another time

Many of North Carolina’s more than 6,000 dams began as mill sites, hydro sources or farm ponds. Those industries are largely gone. The structures remain, often holding back sediment instead of serving a purpose, and are increasingly vulnerable to extreme rainfall driven by a warming climate.

“Dams are part of our textile and manufacturing history,” McCombs said. “But the storms they were built for are not the storms we’re seeing now. Our economy depends on healthy rivers and outdoor recreation. Letting rivers run again makes communities safer.”

Helene’s debris-choked rivers tore up roads, uprooted trees and crushed culverts across the mountains. McCombs spent 11 days without power and 53 days without clean water after the storm.

“Rivers can take care of us if we take care of them,” she said. “When we give rivers room to move, we protect people. But we have to act before the next storm, not after.”

Related: Hurricane Helene by the numbers: A look at the damage to western NC

A familiar warning in a changed climate

Flood behavior in the mountains differs sharply from the coastal plain, and heavier rainfall is amplifying those risks.

“In eastern North Carolina, the goal is to move water out fast,” Council said. “Here, you have to slow it down. Everything is on a slope. Faster water means more destruction.”

The region has seen this before — in 1916, in 1940 and now again, in a warmer world, with Helene.

“If it has happened multiple times, it will happen again,” Council said. “And probably sooner than we used to think.”

At Lake Craig, weeds sprout through cracked pavement near what was once a community pool. McCombs said she swam there just a few years ago. Now the basin is filled with grass, a reminder of how quickly landscapes can change when water carves a new course.

“We have an opportunity to build back smarter,” she said. “Removing high-risk dams and restoring rivers isn’t nostalgia. It’s resilience. The question is whether we act before the next storm — or wait for the failure to find us.”

WRAL documentary explores the aftermath of Hurricane Helene in North Carolina

Last month, WRAL premiered its documentary “Helene: What We Lost, What We Found.”

The WRAL documentary team takes viewers inside the communities hit hardest by Helene’s record flooding and mudslides, and examines what survivors and neighbors discovered in themselves as they began to rebuild.