A team of engineers in Germany has developed a laser-based drill that could change the way humanity explores the icy worlds of our solar system. Instead of heavy mechanical systems or energy-hungry melting probes, this innovation uses precision light to pierce frozen crusts. The technology may soon help scientists reach the concealed oceans beneath Europa, Enceladus, and even icy craters on the Moon and Mars.

Lighting The Way Beneath Alien Ice

For decades, space scientists have dreamed of reaching the vast oceans that lie beneath the frozen shells of moons like Jupiter’s Europa or Saturn’s Enceladus. These mysterious reservoirs may hold the key to discovering extraterrestrial life. Yet the practical challenge of drilling through kilometers of ice has long been a barrier. Now, a new study published in Acta Astronautica outlines an ingenious laser drill that could make such exploration feasible.

Developed at the Institute of Aerospace Engineering at Technische Universität Dresden, the device vaporizes ice using a concentrated laser beam instead of melting or cutting it mechanically. The process, known as sublimation, turns solid ice directly into vapor. This technique eliminates the need for long, power-draining cables or heavy drilling rods.

“We’ve created a laser drill that enables deep, narrow and energy-efficient access to ice without increasing instrument mass — something mechanical drills and melting probes cannot achieve,” explained Martin Koßagk, lead author of the study.

Unlike traditional systems that grow bulkier with depth, the Dresden team’s design keeps all components at the surface. The vaporized ice escapes through a narrow borehole, carrying dust and gas samples that can be analyzed for chemical composition, density, and even potential biosignatures. In doing so, the technology not only reduces power consumption but also makes subsurface exploration possible on small landers that cannot afford heavy payloads.

Challenges Hidden Beneath The Surface

While promising, the laser drill faces its share of obstacles — quite literally. Beneath layers of dust or stone, where no ice exists to be vaporized, the beam cannot proceed. These interruptions would force mission planners to reposition the drill and begin anew. That’s why Koßagk and his colleagues emphasize the importance of integrating complementary tools.

“It is therefore important to operate the laser drill in conjunction with other measuring instruments,” Koßagk told Space.com. “Radar instruments could look into the ice and locate larger obstacles, which the laser drill could then drill past.”

Such synergy could allow mission engineers to map the subsurface structure of an icy world before drilling, ensuring the most promising and accessible locations are targeted. The team also plans to develop a dust-separation unit and miniaturize the system for future space qualification tests. The prototype has already shown its efficiency in field trials in the Alps and Arctic, boring through layers of snow and ice with impressive speed while consuming minimal power.

Beyond space exploration, the same technology could be used on Earth for avalanche prediction and snow-density studies. Mounted on a drone, the lightweight drill could safely gather data from hazardous slopes without risking human lives.

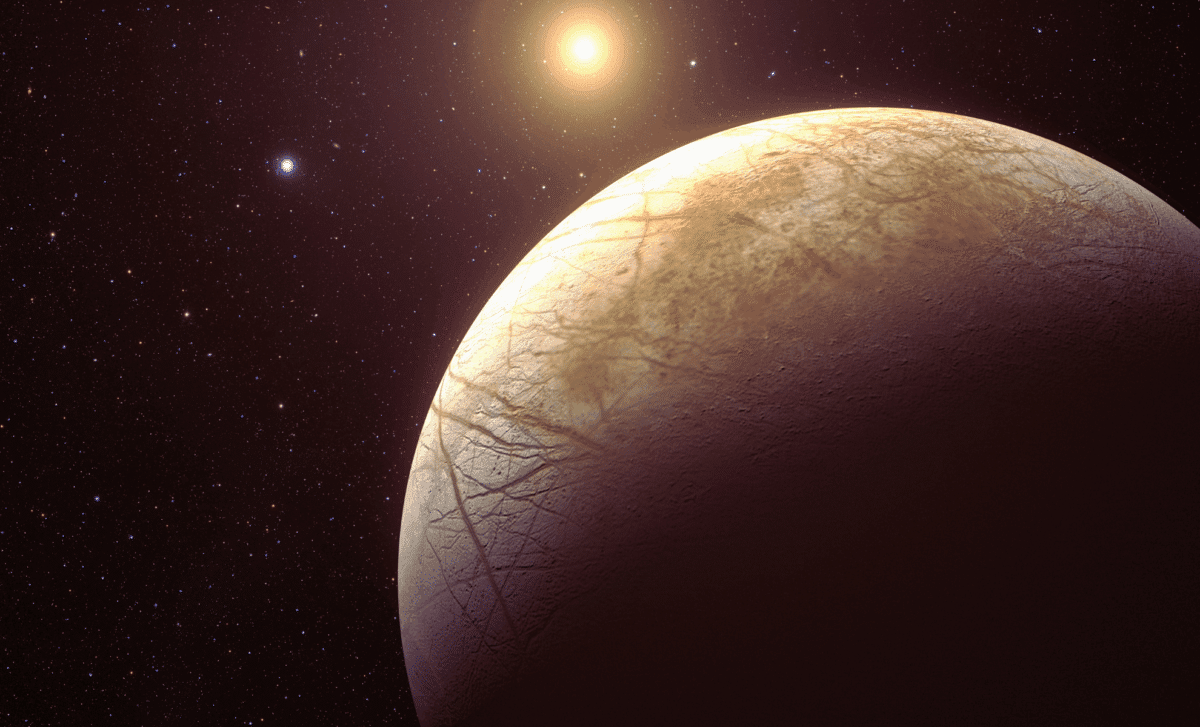

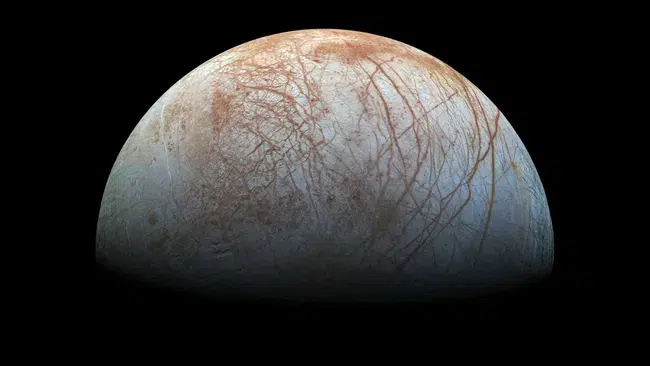

Jupiter’s icy ocean moon Europa, as seen by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft. (Image credit: NASA)

Jupiter’s icy ocean moon Europa, as seen by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft. (Image credit: NASA)

Beneath The Ice Lies The Future

The prospect of exploring what lies beneath the frozen crusts of other worlds has captivated scientists for decades. With this laser drill, that vision edges closer to reality. On moons like Europa, where a vast saltwater ocean hides beneath a shell of ice possibly tens of kilometers thick, such technology could offer humanity’s first direct glimpse into an extraterrestrial sea. These environments, kept warm by tidal forces from their parent planets, are among the most promising places in the solar system to search for signs of life. Until now, accessing them has been beyond the limits of conventional drilling systems.

The laser-based approach changes that equation entirely. By vaporizing ice instead of melting it, the drill minimizes power use while maintaining precision, avoiding the complications of freezing refreezes or mechanical jams. Scientists envision pairing it with mass spectrometers and dust-analyzing instruments to study the gases and particles released during drilling. Such analyses could reveal the chemical makeup of subsurface layers — salts, organics, or isotopic ratios that hint at hydrothermal processes or biological activity. In these measurements, even the smallest deviation could point to a past or present habitable environment.