For weeks, Renae Haymaker was talking to neighbors about the smell drifting from the open pits filled with oil and gas waste a few miles away.

Haymaker, the elementary principal at Hillsdale Christian School outside of Enid, said it smelled like a “buried body.” The smell would fill cars as families drove their kids to school down the main road, making noses burn, according to over 40 complaints sent to the Oklahoma Corporation Commission earlier this year.

“We didn’t know what it was or if it would harm anyone,” Haymaker told The Frontier.

The pits belong to Nemaha Environmental Services, a local oilfield waste disposal company. The company treats mud, wastewater and other debris from oil and gas production.

One woman wrote to the state that she was vomiting and suffering from headaches. A local doctor wrote that he worried about the health of people living in the area. A town official asked the state to step in. A volunteer firefighter with the Hillsdale-Carrier Fire District said concerned residents had been calling 911.

Many of the complaints came after Nemaha accepted 7,500 barrels of material not covered by its state permits, mainly spent caustic wash from a refinery in Wisconsin, according to state records. The caustic wash was primarily sodium hydroxide, a common chemical but one that can pose serious health hazards like eye damage and skin burns, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

A spray-painted sign hangs from a fence outside of Nemaha Environmental Services north of Enid. KAYLA BRANCH/The Frontier

A spray-painted sign hangs from a fence outside of Nemaha Environmental Services north of Enid. KAYLA BRANCH/The Frontier

The company told state inspectors that the substance was being used in a way that would exempt it from federal rules regulating hazardous waste. State regulators initially weren’t sure who had jurisdiction to handle the “improperly disposed of” materials, records show.

Federal law exempts some materials created during oil and gas production from hazardous waste rules, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. These materials can still be dangerous to human and environmental health, according to the EPA, but they aren’t required to follow the same cradle-to-grave tracking and disposal standards.

The Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality said it does not track how much waste like this the state receives from out of state each year.

Sen. Roland Pederson, R-Burlington, made phone calls to state officials in an effort to push for enforcement.

Pederson said residents in his district have had concerns about Nemaha for years. At one point, a local resident sent state regulators photos of animals that the resident said had wandered onto his land, covered in oil.

But the smell from the out-of-state waste was “above and beyond anything that was imaginable,” he said.

“It’s unfortunate the people in that area had to deal with that,” Pederson said.

State regulators shut Nemaha down in February while they investigated. An administrative law judge for the Oklahoma Corporation Commission eventually recommended a $15,000 fine for receiving an unauthorized substance. But the three Corporation Commissioners have not yet voted to approve that recommendation. The agency said in October that there are no open or pending enforcement actions but that the situation remains “an ongoing investigation currently in a cleanup phase.”

A creek runs behind Nemaha Environmental Services’ property north of Enid. KAYLA BRANCH/The Frontier

A creek runs behind Nemaha Environmental Services’ property north of Enid. KAYLA BRANCH/The Frontier

Nemaha is also facing a possible criminal investigation by the Oklahoma Attorney General’s office, according to court documents filed in July. The Attorney General’s office said it could not comment on any pending investigations.

The company spent the last several months asking the Corporation Commission to allow it to resume operations, saying it had lost $1.5 million since being shut down. But the company pulled its request at the beginning of October. Nemaha’s lawyer did not return several requests for comment.

Support Independent Oklahoma Journalism

The Frontier holds the powerful accountable through fearless, in-depth reporting. We don’t run ads — we rely on donors who believe in our mission. If that’s you, please consider making a contribution.

Your gift helps keep our journalism free for everyone.

A spokesperson for the Corporation Commission said the agency does not comment on specifics for active cases.

“OCC responded quickly to initiate an investigation following receipt of a complaint in order to safeguard area residents from the potential of possibly hazardous material being improperly disposed at a site for which a permit had neither been requested nor issued,” a statement from the agency says.

Ambiguous rules for hazardous waste

Less than three miles from Hillsdale, Nemaha Environmental Services’ 320-acre property is surrounded by crops and cattle. Nemaha bought the property from another local company in 2014 for $7.5 million, according to county records.

Nemaha said in court documents that the bad smell happened because the caustic wash it had been accepting from out of state was contaminated with a different chemical. The company said this chemical did not pose a risk to human health and safety.

The company got permission from the Corporation Commission in early 2025 to open a recycling facility on site that would be allowed to handle caustic wash. But the facility is not yet open, according to state records.

Inspectors with the Corporation Commission initially wrote that Nemaha had received a substance the agency did not regulate. The Corporation Commission told a community resident that the state Department of Environmental Quality would manage the material, according to one state report. The Department of Environmental Quality said Nemaha didn’t have a permit with the agency so it didn’t have jurisdiction over the facility.

Hillsdale is less than three miles away from Nemaha Environmental Services. Residents say they could smell the fumes from Nemaha. KAYLA BRANCH/The Frontier

Hillsdale is less than three miles away from Nemaha Environmental Services. Residents say they could smell the fumes from Nemaha. KAYLA BRANCH/The Frontier

The chemicals Nemaha received are exempt from typical hazardous waste rules since the company said it had a beneficial use for them, a spokesperson for the Department of Environmental Quality said. For years, Nemaha had issues with oil in its pits and was using the chemicals to break up the oil, the company detailed in a court filing.

Madison Miller, deputy executive director for the Department of Environmental Quality, said federal regulations allow for a waste generator to decide whether something is exempt from hazardous waste rules.

If a company does not follow guidelines, or if state regulators disagree that something is exempt, they could talk to the company before escalating to other enforcement actions, said Skylar McElhaney, a spokesperson for the Department of Environmental Quality.

Since Nemaha’s waste was exempt, the Department of Environmental Quality, which typically handles hazardous waste issues in Oklahoma, has no authority over the situation beyond offering technical assistance to the Corporation Commission, McElhaney said.

Greg Mahaffey, an attorney representing landowners who don’t want Nemaha to reopen, wrote in court documents that Nemaha’s use of caustic wash is “harmful to skin, eyes and lungs if contacted or breathed.”

Mahaffey is also arguing that Nemaha shouldn’t be allowed to open the on-site recycling facility. But he told a Corporation Commission judge in early October that the landowners would give Nemaha until next spring to clean up the site before moving forward with their case.

Past problems

Nemaha has a history of regulatory violations and complaints filed against the company, records show.

In 2018, an inspector with the Corporation Commission cited the facility for problems with oil films in its pits. Five years passed, and the company still had not fixed the issue in 2023, resulting in a $3,000 fine.

Nemaha was also the company responsible for the 2023 oil spill in Garfield County where roughly 1,000 barrels of oil contaminated a local creek. The pit that leaked does not have a permit, regulators found recently, and also doesn’t have a special kind of liner used to prevent chemicals leaching into the surrounding soil and water.

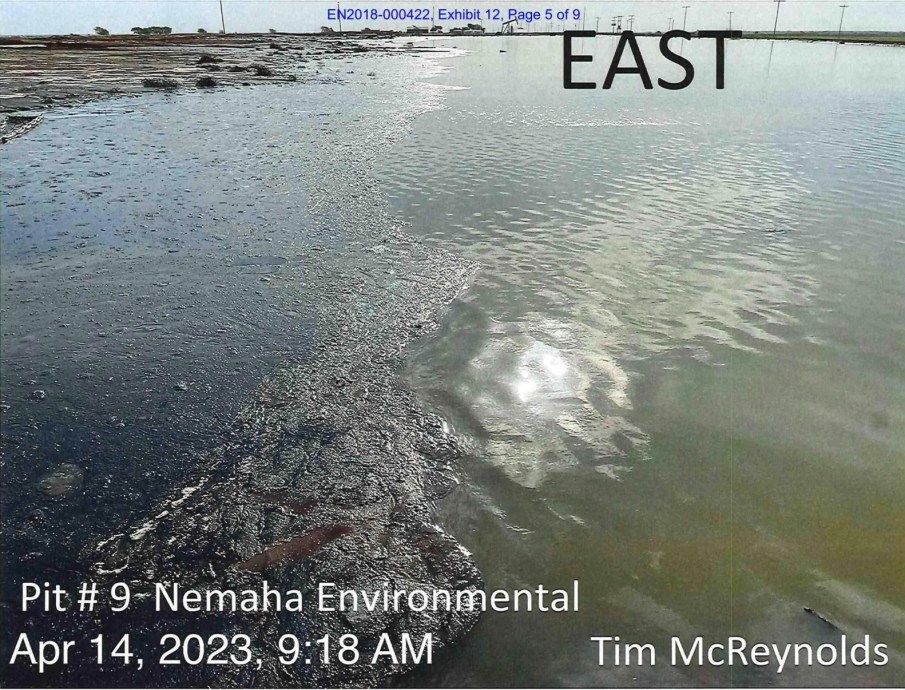

Pit #9 at Nemaha Environmental Services has had issues for years. Nemaha added unpermitted chemicals into the pit in an attempt to address these issues, the company said. Photo provided.

Pit #9 at Nemaha Environmental Services has had issues for years. Nemaha added unpermitted chemicals into the pit in an attempt to address these issues, the company said. Photo provided.

In August, Nemaha was cited for a series of new violations, including overflowing pits, tears and holes in pit liners and downed fencing. The company was also written up for an open pit that it told state regulators was closed.

Operators typically get several weeks to fix these kinds of deficiencies. A judge has approved several extensions in Nemaha’s case.

In May, eleven landowners sued the company in Garfield County District Court seeking monetary damages for allowing “harmful substances” to spill onto their properties, causing contamination to vegetation, wildlife, soil and water. The lawsuit also alleges that Nemaha failed to then clean up the pollution. The plaintiffs’ lawyers did not respond to several requests for comment.

The lawsuit is still pending, and Nemaha has denied all of the allegations, according to court documents. The company’s attorney in the case did not respond to requests for comment.

Federal environmental laws may prevent the landowners from successfully suing Nemaha on some claims, the company argued in court documents.

By mid August, the acrid smell had mostly left the air, Haymaker said. She said the state never responded directly to her complaints about Nemaha.

“I didn’t think that they were shut down,” Haymaker said. “I just thought they were doing what they should have been doing from the beginning.”

Related stories