The tool, known as variable-shutter pair distribution function or vsPDF, represents a leap in time-resolved material analysis, reaching speeds 250 million times faster than the best digital cameras. Developed by researchers from Columbia University and the Université de Bourgogne, the technology captures atomic behavior that traditional crystallography has long blurred or missed.

Energy materials, used in applications like solid-state refrigerators or converting heat to electricity, often behave erratically at the atomic level. This is due to clusters of atoms shifting positions dynamically, not statically, across time. Until now, such movement couldn’t be separated from ordinary atomic jittering. That’s what vsPDF changes. According to Columbia’s Simon Billinge, this is “a whole new way to untangle the complexities of what is going on in complex materials, hidden effects that can supercharge their properties.”

The Atomic Choreography inside Materials

To record these invisible motions, the vsPDF method bypasses conventional optics. Instead, it relies on neutrons generated at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory. These neutrons interact with atoms inside the material sample. By tweaking the energy window, effectively the “shutter speed”, scientists can freeze or blur atomic movements across picosecond scales, catching atoms in their most active states.

With a slow shutter, dynamic disorder fades into the background. But with the trillionth-of-a-second speed, researchers can distinguish active atomic clusters, those contributing to energy conversions, from atoms merely vibrating in place. “With this technique, we’ll be able to watch a material and see which atoms are in the dance and which are sitting it out,” Billinge explained.

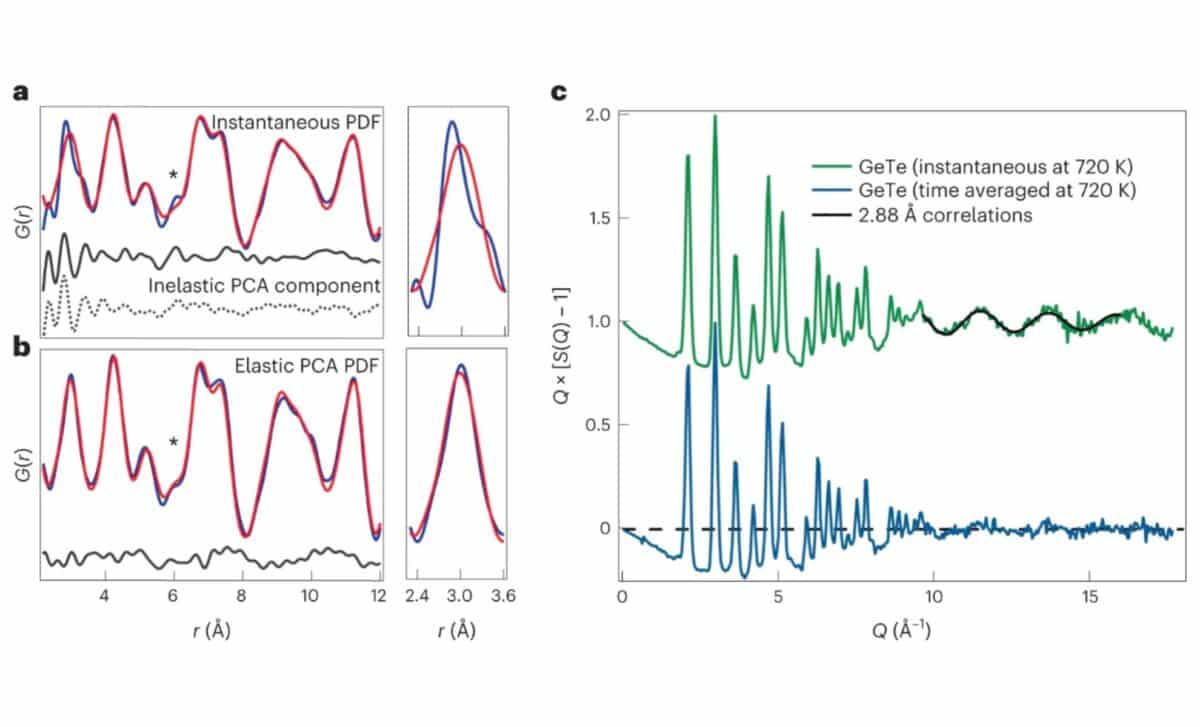

According to findings reported in Nature Materials, the technique provided clarity on germanium telluride (GeTe), a material prized for its ability to convert waste heat into electricity. For decades, GeTe’s atomic disorder puzzled scientists, but vsPDF exposed that the material maintains its average crystalline structure at all temperatures, while also revealing fast, directionally biased motion at high temperatures.

Disorder That Makes Materials Work Better

This kind of “disorder,” paradoxically, is exactly what makes materials like GeTe function so well. Dynamic disorder allows atoms to shift in coordinated clusters, enabling the conversion of thermal energy into electric current, or vice versa. Using vsPDF, scientists saw that fluctuations in GeTe intensified at higher temperatures, aligning with the material’s intrinsic electric polarization, a discovery that hints at how heat is transported and manipulated at the smallest scales.

In the data collected at 720 K, changes in energy were found to produce not just random jiggling, but structured, directional motion of atoms. These fluctuations mimicked static disorder when frozen in time but were shown to be correlated ferroelectric fluctuations, revealed by comparing time-averaged and instantaneous snapshots of the atomic arrangement.

Billinge’s co-lead on the project, Simon Kimber of Université de Bourgogne, collaborated with teams at Argonne National Laboratory and ESRF, confirming that GeTe doesn’t just host atomic instability, it thrives on it. This insight settles long-standing contradictions between diffraction and local probe data. According to the research, GeTe’s dynamic symmetry breaking had previously been mistaken for structural disorder. It was, in reality, fast atomic choreography.

Paving the Way for Better Energy Materials

By distinguishing between static and dynamic disorder, vsPDF opens a new pathway for improving energy efficiency in materials used in critical systems. For example, thermoelectric devices on Mars rovers rely on materials like GeTe to convert radioactive heat into electricity when sunlight is unavailable. Knowing exactly how atomic fluctuations contribute to such performance could improve next-generation components for both space exploration and sustainable energy.

The vsPDF method has already enabled the team to develop a new theoretical model to explain how fluctuations form in GeTe and how external forces might be used to manipulate them. As reported by Columbia University, the goal now is to make the technique more accessible. Currently, it requires specialized neutron sources and expertise, but efforts are underway to standardize it for wider use in material science.

According to the Nature Materials paper, vsPDF is not yet a turnkey system, but its impact is already proving disruptive. From studying atomic movement in battery electrodes to tracking how materials behave during solar-powered water splitting, the technique is set to inform decades of research.