A week ago, the crisis became an armed conflict. The United States formed a joint task force and led a coalition of allies and partners, with the JTF establishing a joint operating area and assigned battlespace and authorities to subordinate task forces. However, due to national policy some of the battlespace was designated a bilateral operating area, in which the partner forces operated within a parallel command structure. Coordination centers were established to generate unity of effort, in the absence of unity of command. However, kill chains were not being closed. Bilateral intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets remained misunderstood, preventing integration. With no common intelligence picture, forces could not pass target custody. Several engagements were successful but came at a high cost in munition expenditure due to redundant targeting.

Individually, each nation had a plan to deliver lethal and nonlethal effects. But the bilateral efforts remained asynchronous.

The result: friendly losses and missed opportunities to defeat the adversary.

The vignette is not speculative fiction; it is the operational reality in the Pacific. A potential fight in that region will hinge on America and its allies’ ability to construct a bilateral battle network. The opening and closing of kill chains are complicated by parallel command structures, where countries retain command and control of their forces. These considerations, coupled with the decades-long work of building battle networks, can now move planning concepts to realized capabilities in the Pacific. In 2021, Todd Harrison, then a director and senior fellow at CSIS, identified five functional elements that comprise a battle network. The elements included sensor, communications, processing, decision, and effects. This battle network is another way to describe kill chains or a reconnaissance-strike network. While the crux of Harrison’s article was an examination of a unilateral US battle network, when we place the discussion in the context of bilateral (or multilateral) combat operations, we discover that battle networks organized in a parallel command structure will face substantial barriers hindering the completion of a dynamic targeting cycle. Against the backdrop of looming threats in the region and a significant shift in the United States’ expectations of its regional allies, building bilateral battle networks is now imperative.

The current under secretary of defense for policy, Elbridge Colby, has outlined a pivot to the Indo-Pacific through an increase in resources as part of a vision to bolster partnerships and counter China’s influence. At the same time, there have been calls for partners and allies in the region to increase their defense spending, making security relationships more equitable. Amid these shifts, it is important to account for existing command structures. During Colby’s confirmation hearings in March, he “expressed [skepticism] of a ‘NATO-like alliance’ in the Indo-Pacific, preferring more tailored bilateral relationships.” This opens the possibility that each tailored bilateral relationship will operate under a different multinational command structure. In multiple conflicts, US forces have operated in an integrated or a lead-nation command. However, Joint Publication 3-16 identifies the parallel command structure as a third option. In a parallel command, the bilateral force does not reside under a single commander; each nation retains command authority and the two nations synchronize actions through coordination centers. In this arrangement, the battlespace may be a bilateral operating area without neat lines or clear delineations of responsibilities between commanders. But how do the five elements of a battle network operate in a parallel command structure?

Sensor Element

The sensor element includes the assets that conduct the first two steps of the targeting cycle, find and fix. Assuming the bilateral sensors can detect, characterize, and confirm potential targets, the parallel command structure will still degrade the bilateral force’s ability to complete the kill chain, for two main reasons. First, the asset in the sensor element needs to be tasked and positioned, but priorities may not be aligned between the bilateral force. In a lead-nation or integrated command structure, the single commander can task the assets, which is not necessarily the case in a parallel command structure. This can lead to a mismatch of the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets in the battlespace, redundancy, or gaps—even if there are sufficient means. Bilateral priority intelligence requirements could help to solve the problem of what to prioritize, and these should be drawn from existing unilateral priorities and not generated independently.

Second, there is the question of whether the transmission of data can create a common intelligence picture. This question appears to blend into the processing element and the ability to fuse the data, but it directly affects the number and types of sensors that need to be applied to a target. If the bilateral force cannot share track data, will two sensors be required to provide target-quality data to the effects element? The requirement of passing digital tracks may not be unique to a parallel command structure, but having two separate intelligence pictures in different intelligence operations centers is.

Communications Element

There is no dedicated step in the dynamic targeting process associated with the communications element. However, the communications element underpins every step. With US systems, there are issues with data sharing across different systems. However, the parallel command structure exacerbates this condition. Is the bilateral force sharing transmission methods within the communications element or are efforts duplicated? Is the data passed from the sensor to the processing element shared instantaneously or is there a gap caused by hardware, software, or policy? If the shared communications element cannot create a single mesh network, then the communications from sensors to processing elements will also double—not in a redundant or self-healing fashion, but rather with each communications element passing its own data in unilateral chains. The two unilateral chains then rely on coordination centers at echelon that exchange the information with written notes in a swivel chair fashion.

Activity in the communications element also creates targeting data for the adversary. The parallel commands increase the number of command-and-control nodes that are passing and receiving data while also generating an additional information exchange requirement for the partner commands to synchronize actions. Further, the two commands operating within the same battlespace may not be operating under the same signature management conditions to limit emissions.

Processing and Decision Elements

The processing element comprises the cells and centers necessary to conduct the tracking and targeting functions. Here, too, the challenge arises from a lack of unity of command. It is possible for there now to be two priority target lists, one for each commander. Within the targeting step, multiple assets may need to be coordinated to maintain the continuity of the track and custody of the target. In a contested environment, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance will be at a premium and those assets must be prioritized. However, there is not a single commander that can prioritize those assets.

During the targeting phase of a dynamic targeting cycle, options for weapons are selected, the battlespace is deconflicted, and risk is assessed. Except, under a parallel command structure, the centers need to manage this fight bilaterally. Based on the weapons available, how are targets matched to the available weapons with a coordinated time on target? A conflict exists if the target is a high-payoff target for one commander but not the other. The maximum benefit may be achieved with a bilateral and joint strike capability to strike the adversary from multiple directions with different types of munitions and effects. However, the joint and bilateral strike may come at the cost of time—a distinct disadvantage when the ability to maintain the target track is fleeting.

In an ideal situation, the respective targeting centers are geographically colocated. The cost to coordinate tracking and targeting is measured in time and work at additional boards, bureaus, and working groups. However, if the centers are not geographically located then there will be an increased burden on the communications element. Additionally, if we trace back to the sensor element, what if the sensor data cannot be shared and there is no common intelligence picture? Liaisons can be in place to pass information but at best this challenge will slow down the system. At worst, some tracks may be redundantly targeted while others have no weapons allocated against them.

In a simplified sense, the decision element is the commander. In a unilateral command, the commander approves the plan developed by the processing element and the orders are transmitted to firing agencies generating lethal and nonlethal effects. However, within the parallel command structure, the two commanders may or may not agree on the plan.

The Battlespace Conundrum

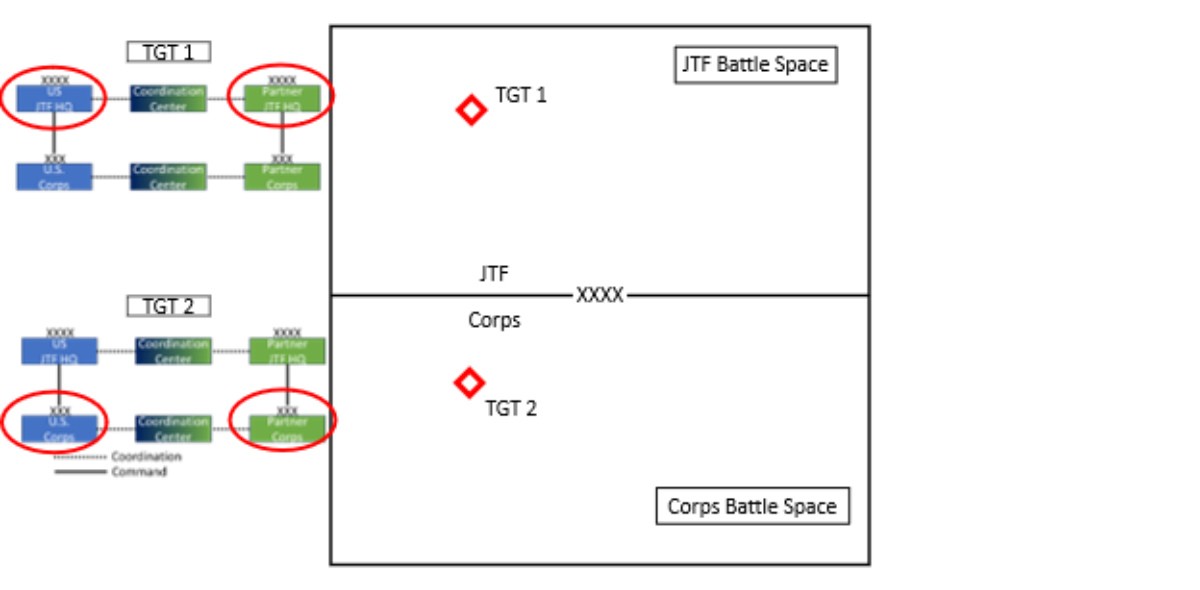

In addition to the complications posed by parallel command structures to the various elements of a battle network, there is an additional challenge that arises by battlespace division. Consider figure 1 below. The battlespace is arranged so that the partners at echelon share the same area of operations. Target one is in JTF battlespace for both countries. The JTF elements conduct the targeting cycle, coordinate at echelon with one another, and engage the target. Similarly, the two corps headquarters complete the cycle for target two.

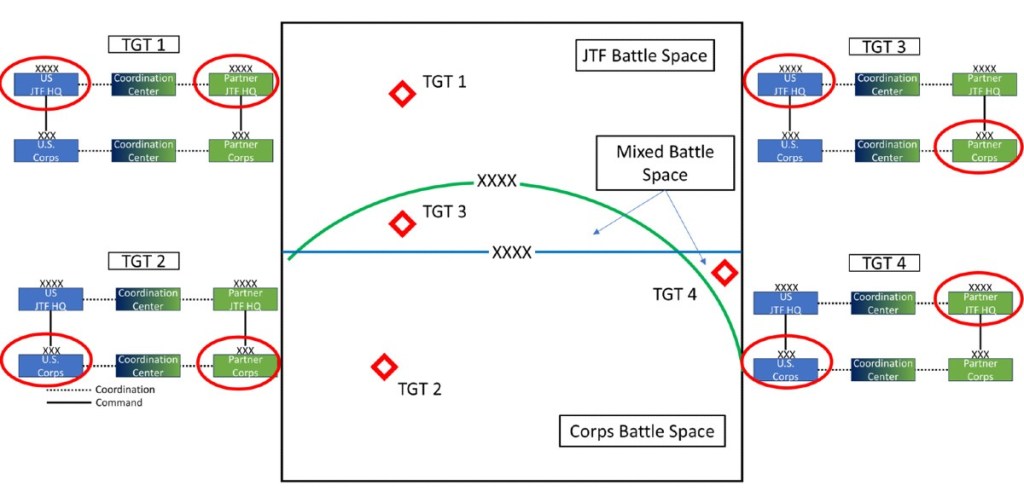

Now consider figure 2. The partner assigns battlespace based on the maximum effective range of its fires, resulting in an arc, while the United States assigns it linearly. The battlespace is no longer neat and areas of operation no longer match each other. The process for targets one and two remains as it did in figure 1 but now targets three and four have emerged as new combinations, with a JTF headquarters prosecuting targets with a partner’s subordinate headquarters. While not an impossible problem to solve, the new possibilities increase layers and slow the kill chain.

And Then There’s Logistics

Harrison’s model is a powerful means of envisioning various elements of battle networks, but it gave little attention to the role of logistics and sustainment. Logistics is not only an enabler but connects all operational functions. In a bilateral context, mutual support and reliance upon partners not only extend capabilities and accelerate the targeting cycle but also build trust. The high demand for munitions coupled with complex movement requirements impose constraints on the availability and accessibility of shared ammunition stocks. In the parallel structure, additional risk is added to the commanders due to a lack of a common logistics operating picture. Logisticians must be able to clearly articulate the resource demands and limitations associated with each function of the bilateral battle network. Only with this understanding can commanders accurately assess operational feasibility to support the bilateral force.

A Way Forward

Bilateral forces can work through these identified problems through robust field training exercises, command post exercises, and wargames. In the right environment, the partnered commanders and staffs learn, understand, and execute. Target priority lists may differ between each nation’s JTF but exercises identified those differences and enable each command to know how to work with those differences. The bilateral force shares a common intelligence picture with reciprocity rights for subordinate units to edit tracks and populate those tracks on it. Further, the bilateral force shares and accepts an understanding of the prosecution of targets according to national priorities. Within the communications element a redundant and resilient plan is built and rehearsed allowing data to flow through primary, alternate, and contingency modes. Policy barriers to data exchange were identified during field training exercises and the right authorities requested at the onset of the crisis. The process elements conducting tracking and targeting are geographically separated but the previous rehearsals identified exchange requirements for liaison officers and subject matter experts. Each targeting team understands the strengths and weaknesses of the bilateral force effects elements. The right type of weapon is allocated to the target to minimize excess munition expenditure. A common logistics operating picture informs the target cell and the commander where the critical munitions are and when the next resupply can arrive. The current operational picture and risk to future missions inform the current fire mission. This leaves the commander with a very different end state than the opening vignette.

Lieutenant Colonel Scott Blyleven is the III Marine Expeditionary Force director of deliberate plans. He previously served as the 3D Marine Expeditionary Brigade Japan plans officer, during which time the brigade executed five major exercises with elements from the Japan Ground Self Defense Force and rehearsed bilateral operations in a parallel command structure.

Major Benjamin VanHorrick currently serves at the Department of Defense Inspector General. During the 3D Marine Expeditionary Brigade’s bilateral exercises with the Japan Ground Self Defense Force, he was the brigade’s current logistics officer.

Major Jennifer Adams is the 3D Marine Expeditionary Brigade’s communications planner.

Captain Jill Dugan is the 3D Marine Expeditionary Brigade’s collections officer.

Major Ricardo Bitanga is the III Marine Expeditionary Force’s fires planner for Japan operations.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Marcos A. Alvarado, US Marine Corps