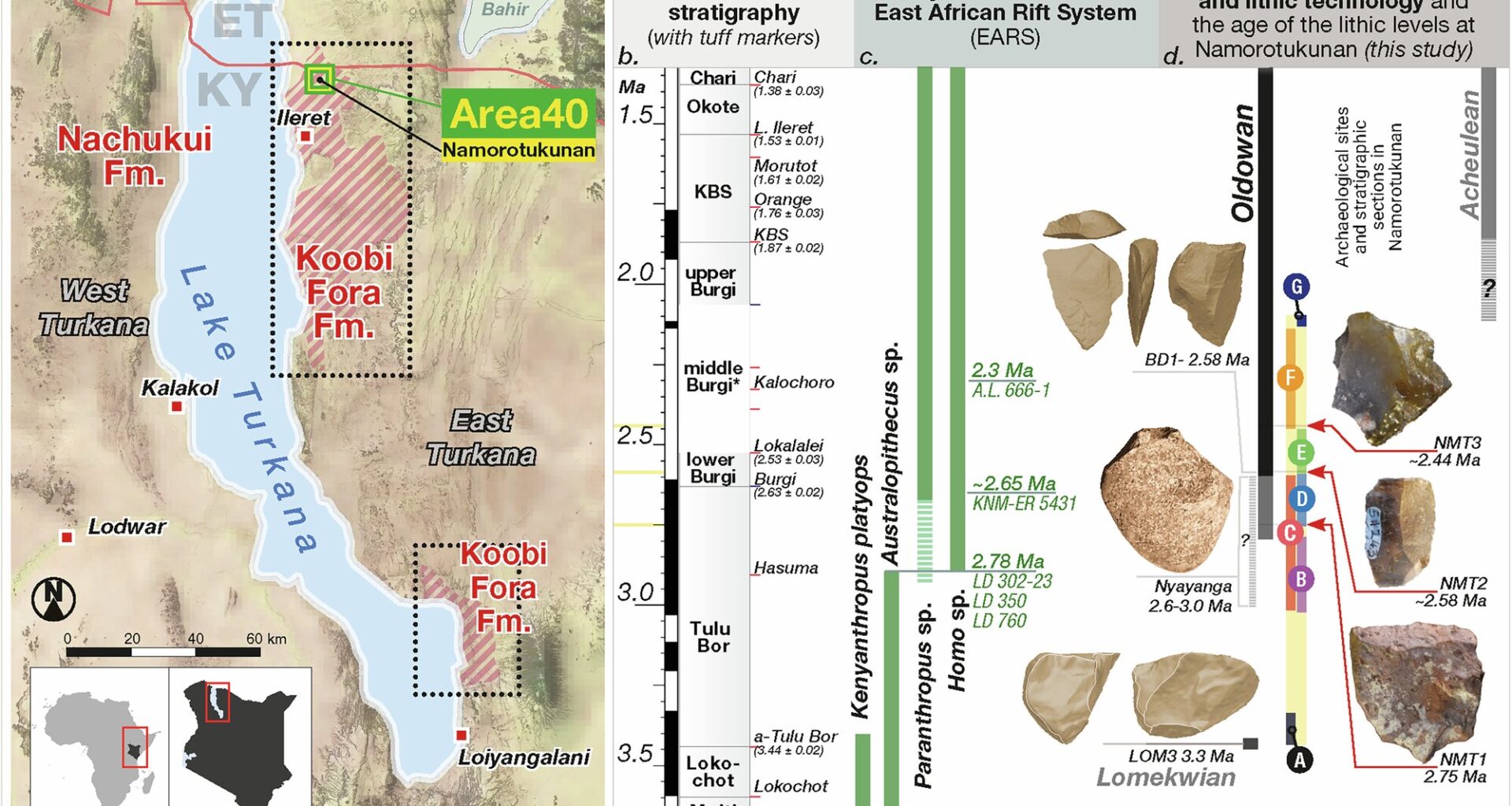

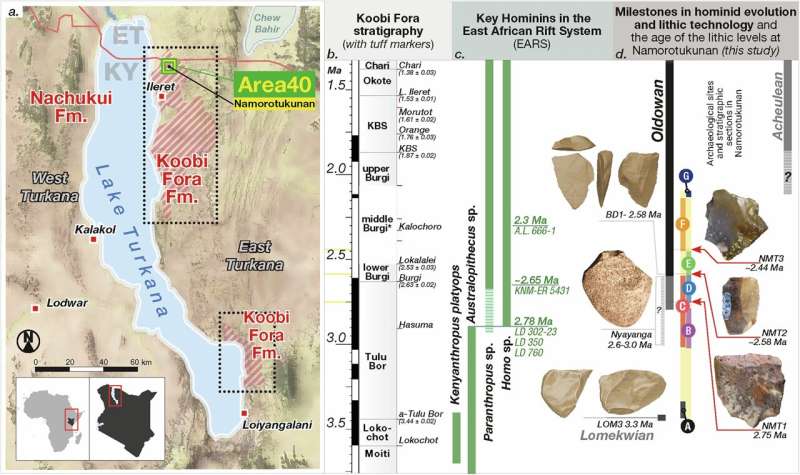

Map of Turkana Basin with the Namorotukunan Archaeological Site and timeline of currently known events in the Plio-Pleistocene. Credit: Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x

Imagine early humans meticulously crafting stone tools for nearly 300,000 years, all while contending with recurring wildfires, droughts, and dramatic environmental shifts. A study published in Nature Communications brought to light remarkable evidence of enduring technological tradition from Kenya’s Turkana Basin.

The paper is titled “Early Oldowan technology thrived during Pliocene environmental change in the Turkana Basin, Kenya.”

An international multi-center research team has uncovered at the Namorotukunan Site one of the oldest and longest intervals of early Oldowan stone tools yet discovered, dating from approximately 2.75 to 2.44 million years ago.

These artifacts—essentially the earliest multi-purpose Swiss Army knives crafted by hominins—demonstrate that our ancestors not only survived but thrived throughout one of the most environmentally volatile periods in Earth’s history.

“This site reveals an extraordinary story of cultural continuity,” said lead author David R. Braun, a professor of anthropology at the George Washington University. He is also affiliated with the Max Planck Institute. “What we’re seeing isn’t a one-off innovation—it’s a long-standing technological tradition.”

“Our findings suggest that tool use may have been a more generalized adaptation among our primate ancestors,” adds Susana Carvalho, director of science at the Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique and senior author of the study.

“Namorotukunan offers a rare lens on a changing world long gone—rivers on the move, fires tearing through, aridity closing in—and the tools, unwavering. For ~300,000 years, the same craft endures—perhaps revealing the roots of one of our oldest habits: using technology to steady ourselves against change,” said Dan V. Palcu Rolier, corresponding author and a senior scientist at GeoEcoMar, Utrecht University and the University of São Paulo.

Key findings

Tech mastery over hundreds of millennia: Early hominins engineered sharp-edged stone tools with extraordinary consistency, showing advanced skill and knowledge passed down across countless generations—a steady legacy.

Cutting-edge science with ancient rocks: Using volcanic ash dating, magnetic signals frozen in ancient sediments, chemical signatures of rocks, and microscopic plant remains, researchers pieced together an epic climatic saga that provides context for understanding the role of technology in human evolution.

Thriving in the face of climate chaos: These toolmakers lived through radical environmental upheavals. Their adaptable technology helped unlock new diets, including meat, turning hardship into a survival advantage.

What the experts say

On the ground, the craft is remarkably consistent. “These finds show that by about 2.75 million years ago, hominins were already good at making sharp stone tools, hinting that the start of the Oldowan technology is older than we thought,” said Niguss Baraki at the George Washington University.

The butchery signal is clear as well. “At Namorotukunan, cutmarks link stone tools to meat eating, revealing a broadened diet that endured across changing landscapes,” said Frances Forrest at Fairfield University.

“The plant fossil record tells an incredible story. The landscape shifted from lush wetlands to dry, fire-swept grasslands and semideserts,” said Rahab N. Kinyanjui at the National Museums of Kenya / Max Planck Institute. “As vegetation shifted, the toolmaking remained steady. This is resilience.”

More information:

David R. Braun et al, Early Oldowan technology thrived during Pliocene environmental change in the Turkana Basin, Kenya, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x

Provided by

George Washington University

Citation:

2.75-million-year-old stone tools may mark a turning point in human evolution (2025, November 4)

retrieved 5 November 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-11-million-year-stone-tools-human.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.