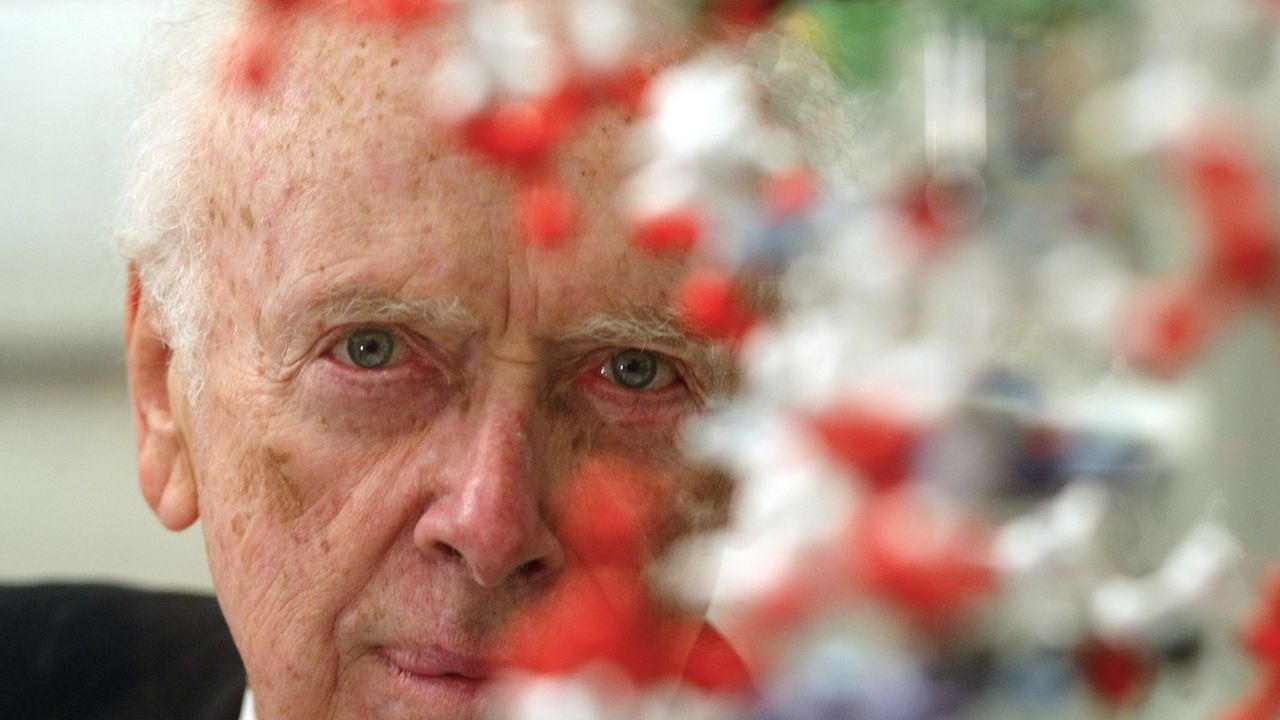

James D. Watson, the Nobel Prize-winning molecular biologist and geneticist and former director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, best known for his discovery of the double helix structure of the DNA molecule, has died at the age of 97, according to a statement from the lab.

He had been in hospice care in East Northport. Before his illness, Watson and his wife, Elizabeth, lived on the grounds of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. He is survived by her and their sons Duncan and Rufus.

Watson’s 1953 paper with British molecular biologist Francis Crick helped explain the structure of DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, the molecule that carries genetic information, allowing organisms to develop and function. The discovery, based on data from Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins and their colleagues at King’s College London, was a “pivotal moment in the life sciences,” according to the lab.

Watson began directing Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1968 while a professor at Harvard University. He then left Harvard in 1976 to become the lab’s full-time director. He served as president between 1994 and 2003 and then chancellor until 2007.

“Watson’s extraordinary contributions to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory during his long tenure transformed a small, but important laboratory on the North Shore of Long Island into one of the world’s leading research institutes,” lab officials said in a statement released Friday.

Despite his accomplishments, Watson was widely condemned for his 2007 comments that Black people have an intelligence inferior to white people due to genetics. He lost speaking engagements as well as all administrative roles at the lab as a result.

When he made similar statements in 2019, the lab’s board revoked his Emeritus status and severed all connections with him, although he continued to live on the campus.

The double helix

Watson shared a 1962 Nobel Prize with Crick and British biophysicist Wilkins for discovering that DNA is a double helix, consisting of two strands that coil around each other to create what resembles a long, gently twisting ladder.

Franklin worked with them on the project. Although she died before they received the Nobel Prize, many historians have criticized Watson and Crick for using some of her research, including a photo of DNA taken with an X-ray called Photograph 51, while neglecting to give her credit and downplaying her contributions.

Their work suggested how hereditary information is stored and how cells duplicate their DNA when they divide. The duplication begins with the two strands of DNA pulling apart like a zipper.

The discovery led to monumental scientific developments such as treating disease by inserting genes into patients, identifying human remains and criminal suspects from DNA samples and tracing family trees.

Watson was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1928, received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Chicago in 1947 and his Ph.D. from Indiana University in 1950.

His work with Crick took place while he was at the University of Cambridge in England.

Cold Spring Harbor Lab

When Watson took over Cold Spring Harbor Lab in 1968, it was described in a Newsday article as “renowned but deteriorating” and near bankruptcy. He revitalized the institution and helped focus its research on the role of DNA in cancer and the molecular basis of the disease.

He also was able to raise funds from public and private sources to expand and renovate the properties, according to the lab’s website, continued the lab’s focus on science education and research and increased publication of laboratory manuals and journals.

The lab said Watson “encouraged the creation of the DNA Learning Center” targeted to high school students.

Watson started the Banbury Center on donated space in Lloyd Harbor. It serves as a think tank for research and policies on life and medical science, the lab said. And he was the first director of the lab’s Cancer Center, designated by the National Institutes of Health.

From 1988 to 1992, Watson directed the Human Genome Project, the federal effort to identify the detailed makeup of human DNA. He created the project’s huge investment in ethics research by simply announcing it at a news conference. He later said it was “probably the wisest thing I’ve done over the past decade.”

Watson was on hand at the White House in 2000 for the announcement that the federal project had completed an important goal: a “working draft” of the human genome, basically a road map to an estimated 90% of human genes.

“He never stopped fighting for people who were suffering from disease,” Duncan Watson said of his father.

With AP

Lisa joined Newsday as a staff writer in 2019. She previously worked at amNewYork, the New York Daily News and the Asbury Park Press covering politics, government and general assignment.