A discovery of ancient rocks might finally answer one of the biggest questions in science: how did the Moon form? Researchers have uncovered chemical clues from 3.7-billion-year-old feldspar crystals that suggest Earth’s early crust has a direct connection to the Moon. The study, led by the University of Western Australia, points to a dramatic event in Earth’s past.

The research, published in Nature Communications on October 31, focuses on rocks from the Murchison region, some of Earth’s oldest surviving crust. Among these, scientists found anorthosites—rocks rich in feldspar—that have preserved isotopic signatures very similar to those found in lunar samples brought back by NASA’s Apollo missions.

A Rare Connection Between Earth and the Moon

Anorthosites, while common on the Moon, are hardly found on Earth. So when researchers in Australia analyzed these rocks, they realized they were holding something special: a glimpse into the chemistry of Earth’s earliest mantle. These feldspar crystals, which grew as molten magma cooled deep below the surface, locked in chemical clues about the planet’s early environment.

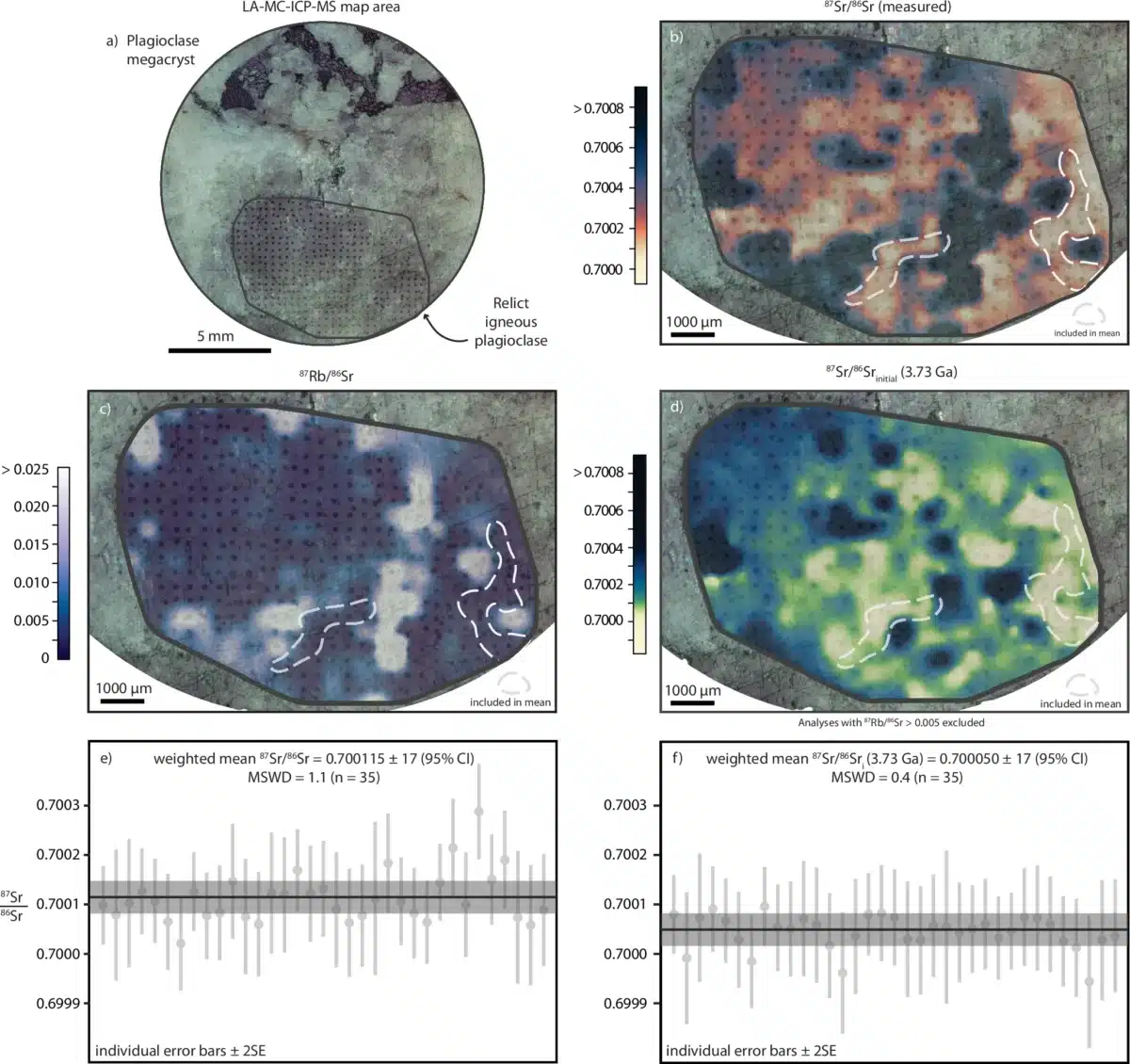

Lead author Matilda Boyce, a Ph.D. student at UWA, explained that the study focused on isolating the “fresh” parts of the feldspar crystals to trace their isotopic signatures. This allowed the team to peek into Earth’s primordial crust. One of the key findings was that Earth’s continental growth didn’t kick off immediately after the planet formed. Instead, it began around 3.5 billion years ago, nearly a billion years after Earth’s birth.

Mapping Strontium Isotopes in Plagioclase from the Manfred Complex. Credit: Nature Communications

Mapping Strontium Isotopes in Plagioclase from the Manfred Complex. Credit: Nature Communications

Linking Earth’s Early Chemistry to the Moon

Even more striking, however, is how closely the isotopic signatures from these ancient Australian rocks resemble those found in the Apollo lunar samples. This connection offers fresh support for the giant impact theory, which has been the subject of much debate over the years. According to Boyce:

“Our comparison was consistent with the Earth and moon having the same starting composition of around 4.5 billion years ago.” She added in the statement that, “This supports the theory that a planet collided with early Earth and the high-energy impact resulted in the formation of the moon.”

In simple terms, this means that the material that formed both Earth and the Moon came from the same cosmic pool. As Boyce put it, the findings align perfectly with the idea that a Mars-sized planet collided with a young Earth, sending debris flying into space, which eventually coalesced into the Moon.

Matilda Boyce, Ph.D. student at the University of Western Australia, holding an ancient rock sample in the lab. Credit: University of Western Australia

Matilda Boyce, Ph.D. student at the University of Western Australia, holding an ancient rock sample in the lab. Credit: University of Western Australia

Earth’s Early History Preserved in Ancient Rocks

The ancient rocks from the Murchison region serve as a time capsule, preserving the chemistry of Earth at a point when our planet was still young and volatile. The feldspar crystals, which have remained remarkably well-preserved for billions of years, allow scientists to get a direct glimpse into Earth’s early mantle, providing clues about how our planet’s crust—and, by extension, life—began to take shape.

For researchers, this is a rare and invaluable opportunity. These ancient rocks offer a window into a time when Earth was far more hostile and dynamic. And the fact that they’ve survived virtually unchanged for so long is remarkable.