Nearly fifteen years ago, scientists spotted something strange in the gamma-ray sky—a faint but persistent glow at the center of the Milky Way that hinted at the possible presence of dark matter slowly destroying itself. Now, new research has reignited the debate over what’s really causing it—and whether this long-sought cosmic mystery might finally be within reach.

A new twist in the dark matter story

The story of dark matter—a substance thought to make up 85 percent of the universe’s mass—has taken yet another turn. A new study in Physical Review Letters, also available on arXiv, revisits a decade-old question about the Milky Way’s heart and the strange signals coming from it.

The research team includes the renowned British cosmologist Joseph Silk, professor of physics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins University and researcher at Sorbonne University’s Institute of Astrophysics. Silk and his colleagues used fresh data from the Gaia mission and powerful supercomputer simulations to reinterpret results from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

Why dark matter still matters

Without dark matter, galaxies simply wouldn’t have formed as quickly as they did. The invisible material acts as a cosmic scaffolding, forming vast filaments that pull ordinary matter together through gravity. Observations of the cosmic microwave background from the Planck satellite also can’t be explained without it.

But because dark matter doesn’t emit light—or interacts only faintly with it—it remains invisible. Scientists know it can’t be made of known Standard Model particles, since that would contradict predictions from Big Bang nucleosynthesis, which describes the early production of hydrogen, helium, and other light elements.

So far, dark matter has revealed itself only through its gravitational effects, outweighing the visible matter in galaxies and clusters. Yet, some theories predict that dark matter particles might occasionally annihilate, releasing detectable bursts of gamma rays in the process.

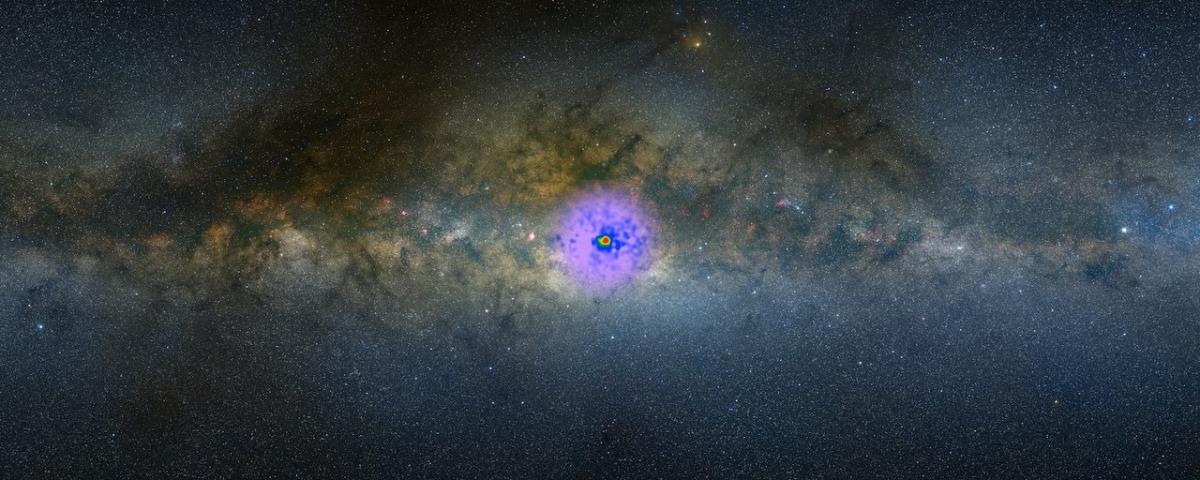

This video begins with a plunge toward the center of the Milky Way using visible-light images. It ends with a superimposition of these images with gamma-ray images taken with Fermi instruments. They show a region approximately 5,000 light-years across that is particularly bright in false color. Red indicates the maximum brightness. © NASA, YouTube

The mysterious gamma-ray glow

Since the late 1970s, researchers have suspected that such annihilations could leave behind a telltale gamma-ray signature. Over the years, Fermi’s telescope has observed an unexplained excess of these high-energy photons coming from the Milky Way’s center—and even from Andromeda.

Most dark matter models predict that these particles should be densest near galactic cores, where collisions are more likely. More collisions mean more annihilations—and potentially more radiation. But in 2015, researchers from MIT and Princeton offered another explanation: pulsars.

Fermi, supernovae, and gamma-ray pulsars. For a fairly accurate French translation, click on the white rectangle in the bottom right corner. The English subtitles should then appear. Next, click on the gear icon to the right of the rectangle, then on “Subtitles,” and finally on “Auto-translate.” Choose “French.” © NASA Goddard

Pulsars or dark matter?

Pulsars—rotating neutron stars that emit powerful beams of radiation—are well-known gamma-ray sources. Because thick clouds of gas and dust obscure our view of the Milky Way’s core, it’s possible that a large population of faint, unresolved pulsars could be creating the same glow once attributed to dark matter.

To test this, scientists modeled the Fermi data. If the signal came from dark matter, the gamma-ray map should look smooth and even. If pulsars were responsible, it should appear patchy and “clumpy.” In 2015, the results seemed to favor the pulsar explanation.

But Silk’s team now says that may have been too simple. Data from Gaia reveals that the Milky Way’s past was anything but calm—it has swallowed several smaller galaxies over billions of years. Those collisions would have stirred up its central dark matter, leaving it unevenly distributed.

By factoring in Gaia’s findings, the researchers used next-generation simulations to show that dark matter could produce the same kind of uneven pattern once thought to rule it out. In other words, the evidence for pulsars and dark matter now stands neck and neck.

A cosmic mystery soon to be solved?

The next generation of gamma-ray telescopes could finally end the debate. The Cherenkov Telescope Array Observatory (CTAO) will deliver images ten times sharper than current observatories like HESS, MAGIC, and VERITAS.

If CTAO detects the unique spectral “fingerprint” of dark matter annihilation, it would be one of the most groundbreaking discoveries in modern cosmology—finally illuminating the invisible matter that has shaped our universe since the dawn of time.

Laurent Sacco

Journalist

Born in Vichy in 1969, I grew up during the Apollo era, inspired by space exploration, nuclear energy, and major scientific discoveries. Early on, I developed a passion for quantum physics, relativity, and epistemology, influenced by thinkers like Russell, Popper, and Teilhard de Chardin, as well as scientists such as Paul Davies and Haroun Tazieff.

I studied particle physics at Blaise-Pascal University in Clermont-Ferrand, with a parallel interest in geosciences and paleontology, where I later worked on fossil reconstructions. Curious and multidisciplinary, I joined Futura to write about quantum theory, black holes, cosmology, and astrophysics, while continuing to explore topics like exobiology, volcanology, mathematics, and energy issues.

I’ve interviewed renowned scientists such as Françoise Combes, Abhay Ashtekar, and Aurélien Barrau, and completed advanced courses in astrophysics at the Paris and Côte d’Azur Observatories. Since 2024, I’ve served on the scientific committee of the Cosmos prize. I also remain deeply connected to the Russian and Ukrainian scientific traditions, which shaped my early academic learning.