When Herwig Schopper arrived in Ithaca, upstate New York, one Saturday in 1960 to spend a year working on electrons with Robert Wilson at Cornell University’s Laboratory for Nuclear Studies, he went straight to the centre. Everything was open, and there was no security. Being the weekend, there was little sign of life other than a man sweeping the floor.

Asking the person he assumed to be a cleaner some questions about the institute, he was surprised by the man’s informed answers. “After a while, I said, ‘Look, you can’t be a janitor here, who are you?’ He said, ‘I’m Bob Wilson.’ I said, ‘What? You’re Bob Wilson, the director of the institute, sweeping the floor on a Saturday afternoon?’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘it’s nothing special’.” Many years later, he tried to introduce floor-sweeping by directors at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (Cern) “but failed completely”, he told James Gillies for the book Herwig Schopper: Scientist and Diplomat in a Changing World (2024).

Schopper was director-general of Cern from 1981 to 1988, overseeing the organisation’s first Nobel prizewinning discovery when Italy’s Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer, the Dutch physicist, shared the 1984 award in physics for their work leading to the discovery of the field particles W and Z, a significant advance in explaining the basic forces of nature. He also paved the way for the installation of the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator, which opened in 2008.

Along the way, he had to balance the competing budgetary pressures of the organisation’s member states, including Britain, which in the early 1980s was seeking a 25 per cent reduction in its contribution. He discovered that this was because Britain, unlike many countries, did not have a dedicated budget for Cern, meaning that its funding was in direct competition with other research budgets. He explained these difficulties to Margaret Thatcher, a scientist by training, when the prime minister and her husband, Denis, visited Cern in 1982. “At the end of her visit, she told journalists that she was convinced that the UK’s contribution to Cern was well spent,” he recalled.

It was not Schopper’s first experience of British bureaucracy. As a young scientist in the early 1950s, he arrived at Harwich on the overnight ferry and told the immigration officer of his invitation to spend a year working at the University of Cambridge with Otto Frisch, the nuclear physicist. His understanding was that he could enter for three months as a tourist and then arrange a visa, but the officer denied him entry and ordered him to take the evening boat back to Hamburg.

He was permitted a call to Frisch to explain why he would not now be arriving in Cambridge. A few hours later, the immigration officer returned and announced that he was now permitted to enter the country. “I was baffled, and I asked what had happened to make him change his mind,” he said. “He explained, ‘Well, Professor Frisch has called us, and we learnt that he is a fellow of the Royal Society and that changed the situation’.”

Herwig Franz Schopper was born in the Czech town of Lanskroun in 1924, the son of Franz Schopper, a secondary school teacher who had not long returned as a prisoner of war from Russia, and his wife Margarethe (née Stark). They divorced soon after their son’s birth and both remarried, effectively supplying him with four parents. His father’s second wife, Friederike, taught him the piano, though his only known public performance was at a Cern staff event in 1988.

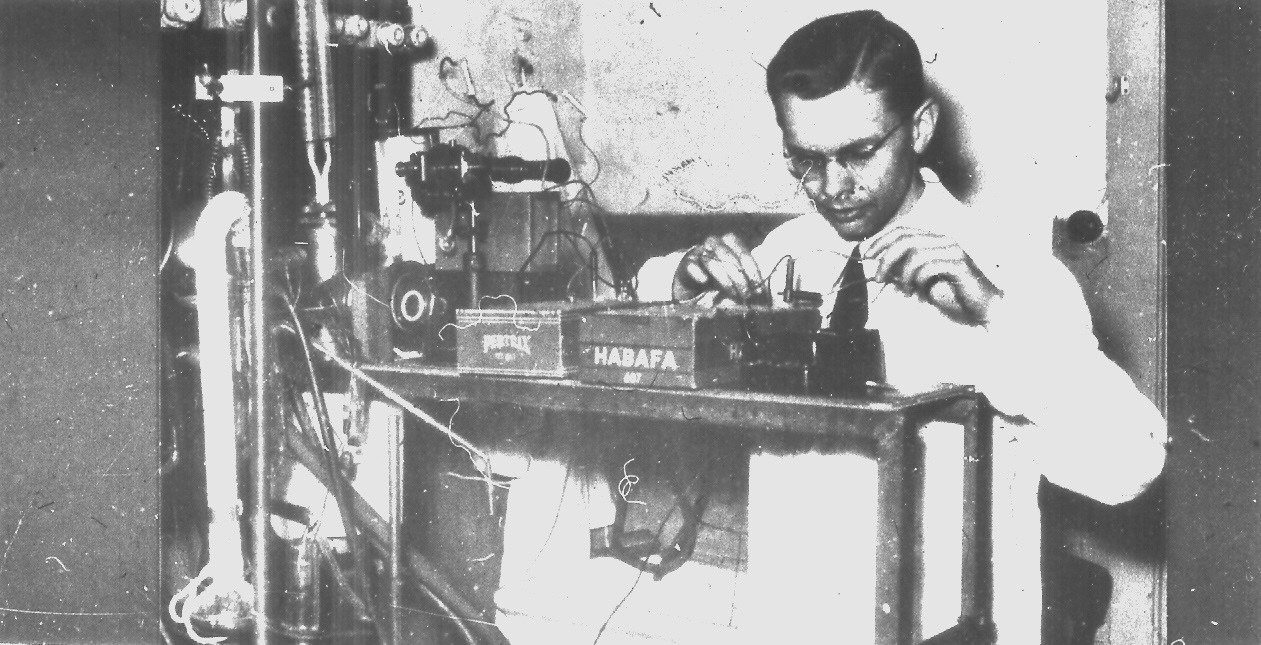

Schopper working in Hamburg in 1956

CERN

As a child, he operated the organ bellows at church during Mass on Sundays. His early ambition was to be a ship’s engineer, but during holidays at his grandparents’ hotel on the Adriatic coast he was fascinated by the conversations between two elderly physicists. “One day they would be talking about how butterflies can fly, the next evening they would be looking at the sky and discussing why the stars are burning, where they get their energy from and things like that. I was so impressed that these gentlemen, these physicists, could discuss such completely different phenomena with such authority,” he said.

In October 1938, the Sudetenland, where Lanskroun is located, was annexed by Germany. Life went on as before until 1942, when he was called up by the Reichsarbeitsdienst, the state labour service. “They immediately started to try to break our will so we would learn to be obedient to orders; that was the hardest thing,” he said. Poor eyesight saved him from being recruited into the Waffen-SS, and instead he was put to work in a munitions factory in a disused salt mine. Later, he was posted with the signals corps to the eastern front in what is now Belarus, before ending up in Berlin.

At the end of the war, he was detained by the British, who found a use for his knowledge of English, gleaned from a Shakespeare teacher in his school days. His captors arranged for him to study physics and optics at the University of Hamburg, though he was still working for the military government when he met Ingebord Stieler, a secretary, in the lifts. They were married in 1949, though shortly afterwards spent a year apart while he worked in Stockholm with Lise Meitner, who had been instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission. Ingebord died in 2009, and he is survived by their children, Doris, who worked in public health, and Andreas, who followed his father into physics, and by Ingrid Krähe, his partner in later years.

Schopper was soon making a name for himself in German physics and in 1958 was offered a chair at the University of Mainz, where he established a new institute for research in experimental nuclear physics, before moving to Karlsruhe, where his research thrived. He returned to the University of Hamburg in 1973, also becoming chairman of the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron centre, known as Desy, developing its role as an international particle physics laboratory and starting its first collaboration with China.

Meanwhile, several European states were beginning to collaborate on Cern, near Geneva, where Schopper spent a year in the Sixties looking at the production of neutrons. He returned intermittently and in 1981 was elected director-general of the organisation. Although he officially retired in 1988, in reality, he did no such thing, remaining in Geneva and keeping an office at Cern. “This gave me the possibility to continue to support Cern, at least in the background,” he explained. He also transitioned from science to diplomacy, overseeing the creation of the Sesame Laboratory in Jordan, a scientific research project modelled on Cern that brings together scientists from across the Middle East.

Schopper continued to enjoy a wide range of cultural interests, including accompanying recordings of piano concertos by Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin, “although I have to confess that I used a computer program to slow down the speed without changing the pitch”, he said. Explaining the relationship between his work and leisure, he once said: “Physics is for the intellect. For emotions, there is music.”

Herwig Schopper, experimental physicist and director-general of Cern, was born on February 28, 1924. He died on August 19, 2025, aged 101