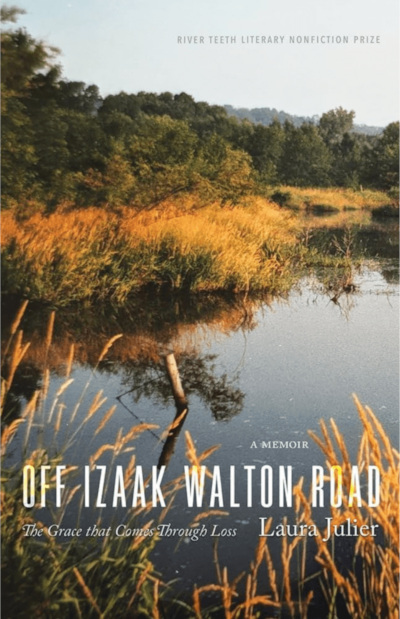

In Becoming Native to This Place, Wes Jackson says, “Either all the earth is holy or none is. Either every square foot of it deserves our respect or none does.” In Off Izaak Walton Road, winner of the River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Prize Laura Julier shows us how true this is with heart, grace and honesty.

The cabin and land on the Iowa River that becomes Julier’s beloved place is an unconventional subject for an entire book. From the author’s own descriptions, this place would not appear in nature magazines or travel brochures. Just beyond ready-mix plants, grain bins, a salvage yard and warehouses, it is “not pretty.” Yet this borrowed cabin on a river oxbow becomes a cherished refuge and a place of profound personal belonging and awakening — and inevitable loss.

Julier’s journey to “R’s” cabin in many ways began years earlier, when she lived in a small house in Iowa City. A job in Michigan forced a move, but the community beckoned her back, where she took up residence in the small cabin on the river for periods of time ranging from days to months.

Her detailed journey with the cabin and land tells a compelling story of connection to place. She shares months and years of close attention and learning — about birds (eagles and owls play prominent roles), about the river itself and its neighboring marsh, about the property’s history (though difficult to trace and remaining incomplete). This intentional familiarity leads to a deep sense of belonging. But even more significant is the development of a profound love for the place as well as self-understanding.

About halfway through the book, an epiphanic moment of opening and release occurs. Tears fall unbidden, and her eyes rise to gaze upon three red-tailed hawks riding the thermals. “Pain and loss continue to dissolve, taken up, the broken and the healed, on the rising air.” This healing moment is central to Julier’s deep connection to this place. Now she can “know that I am right in my skin. That I am in the right place.”

Julier’s relationship to R’s cabin is about being “a part of this ecology,” but it is also about “working free of my own past.” The author at times makes general, if not oblique, references to past abuse, woundedness and loss. Early on, we get a fair measure of understanding of the loss of that first Iowa City home, but no specifics.

Despite that mystery we become quite intimate with the place itself through Julier’s skilled, highly detailed chronicle, and I am grateful for her courage in opening her heart to us readers to the extent she does. We all have experienced sadness and loss, so perhaps knowing we share such wounds generally is enough. Any more detail would serve only to satisfy my curiosity rather than provide a deeper understanding of how powerful a place can be in our lives.

Significant events — natural and human — alter Julier’s relationship with the cabin off Izaak Walton Road. Her deep love for this place makes these changes painful yet also builds resilience within her to withstand them. Laura Julier has provided us not only with a profound demonstration of how to love a place, but also unique insight into how that love serves, supports and clarifies the complexities of the human heart and soul.

This article was originally published in Little Village’s July 2025 issue.