Illustration: Kevin Jeffers, The Colorado Sun; Canva

Illustration: Kevin Jeffers, The Colorado Sun; Canva

COLORADO SPRINGS

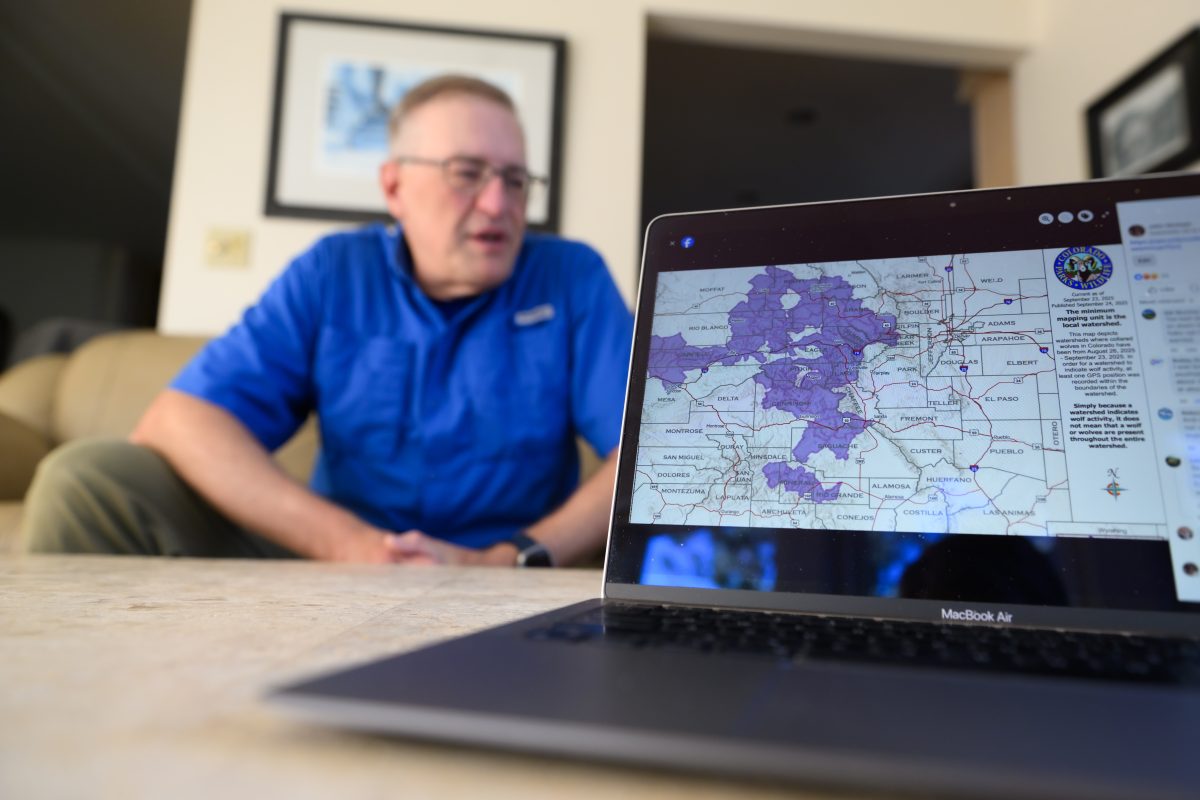

In the 16 years John Michael Williams has lived in a split-level house in a quiet Colorado Springs neighborhood, he has, by his conservative estimate, had 15 deer born in the modest backyard off his glassed-in sunroom.

The does, looking fat in the spring, will jump the fence, poke around, bed down and give birth to either twins or triplets. After they do, he will close the gate for 10 to 14 days, because he doesn’t want predators sneaking in and snatching the cute, speckled fawns, or the does and fawns getting out too early. And he lets them eat whatever they want. “We really don’t have any plants back there,” he says. “We gave up growing flowers because they love them so much.”

Several other wild animals have visited his home, including a buck bigger than any he’s seen in the wild, more deer, a red fox whose presence woke him from a nap in his hammock and a bear he found licking the inside of a Starbucks Frappuccino cup he tossed in the trash before the city banned residents from leaving their cans out except for on collection day.

But something he’s never seen in his neighborhood — and will likely never see — is a wolf. And that’s interesting given how much of the past two years he has dedicated to studying, pondering, discussing and posting about the “magnificent animals” and “ultimate predators” that are “cool to look at” and have incredible senses of vision, smell and hearing.

In fact, Williams became so taken with wolves and Colorado’s voter-mandated wolf reintroduction program when it kicked off in December 2023 that he created a Facebook page he envisioned as a little like the Drudge Report, before it “kind of went left,” that would educate the public through articles he shared from various media outlets.

John Michael Williams at his home in Colorado Springs. Williams hosts the Facebook page Colorado Wolf Tracker. (Mark Reis, Special to The Colorado Sun)

John Michael Williams at his home in Colorado Springs. Williams hosts the Facebook page Colorado Wolf Tracker. (Mark Reis, Special to The Colorado Sun)

The people who found his page were (and are) divided into thirds, he says. “One-third is, you know, ‘kill them all,’ and the other third is ‘we love wolves, they’re the greatest thing in the world.’ And in between those two, the final third or maybe bigger, are just kind of on the fence.”

That’s encouraging because he says he doesn’t want Colorado Wolf Tracker to be “an echo chamber” for its members. Rather, his goal is for the page to be a clearinghouse of information about wolves and a place to hold Colorado Parks and Wildlife accountable as they fulfill the voter mandate to restore the animals west of the Continental Divide, and to monitor the narratives they’re creating as they go about it.

For a while, that’s mostly what Wolf Tracker did — with ample criticism for CPW, Gov. Jared Polis, his administration and his husband, Marlon Reis, an animal-rights activist and outspoken proponent of wolf reintroduction thrown in.

Williams has his own critics who say he foments extremism by giving hardline wolf haters a place to spread vitriol, and that he’s clearly there to agitate. But he says he “reaches out to people on all sides of the issues to give them an opportunity to give their thoughts” and that his main motivations are keeping the public abreast of wolf news and giving people in rural communities, who he sees as having been subjected to reintroduction, a voice, because he’s “seen what unchecked growth of a wolf population can do in a state,” Wisconsin, and he doesn’t want that in Colorado, where he thinks reintroduction was rushed.

Wolf Tracker members aren’t generally as welcoming to reintroduction supporters as Williams says he is, though. That’s evident with a quick scan through the comments on most of the posts.

In January, their rhetoric took what many felt was a dark turn into vigilanteism. And in the 11 months since, as the page has remained a place for Williams to inform, educate and hold CPW accountable, it may also have become more powerful.

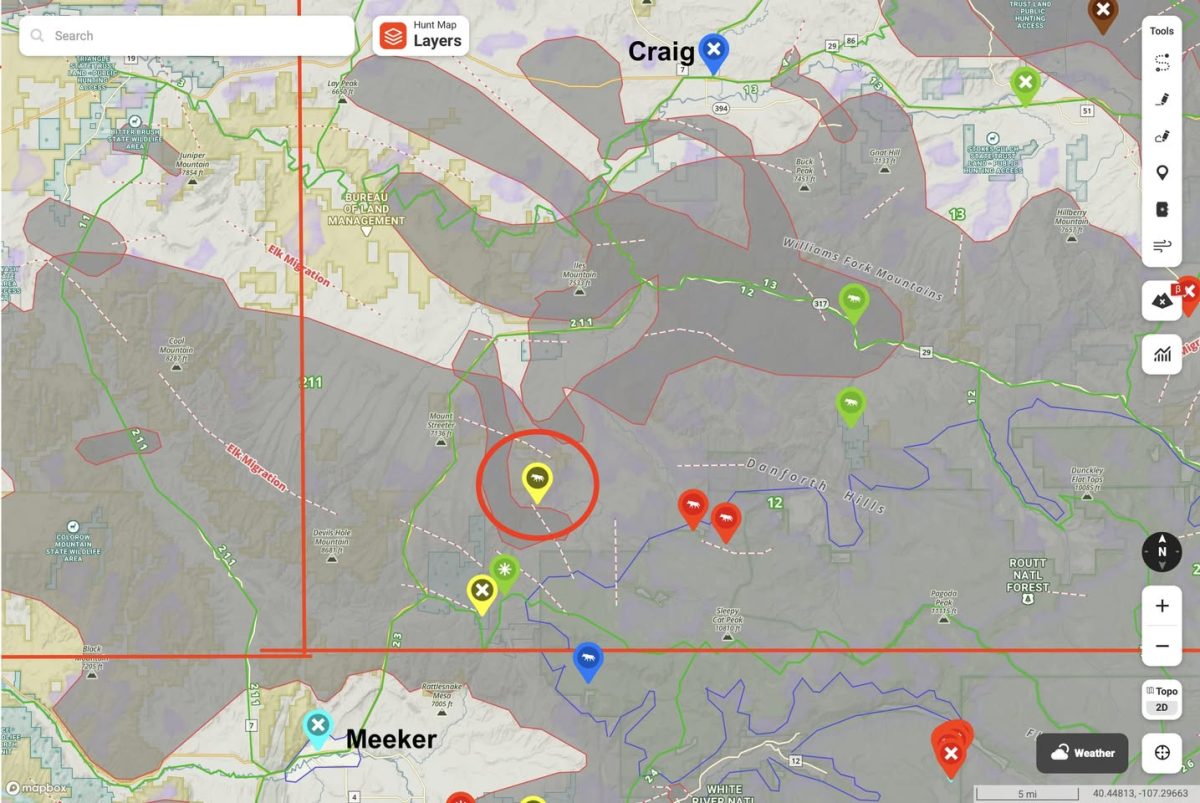

Wolf Tracker’s other purpose is to be a landing page for reports of wolf sightings and depredations in Colorado, accompanied by photos and locations. You’ll often see a map with pins showing these locations. At first, it can be alarming. What if someone who supports the ethos of “shoot, shovel, shut up” zeros in on a wolf and tries to do just that?

Don’t worry. Williams says he never pins “right where someone had found a track and said here it is. You know, latitude, longitude, that sort of thing.” And he shares the pins, he says, “because people that are livestock producers, people that are hunters, recreationists, deserve to know if there are wolves in certain areas. I think that’s something the CPW should be doing. And in the absence of that, I have, at times, posted information with general locations. But never, never the exact spot.”

What keeps the page humming is the ongoing story of wolf reintroduction — or the saga, depending on your view. And members love a good mistake, like the one they the state made when it let voters decide to bring wolves to Colorado at all, and then again on Dec. 18, 2023, when CPW dropped the first five animals in Radium State Wildlife Area in Grand County.

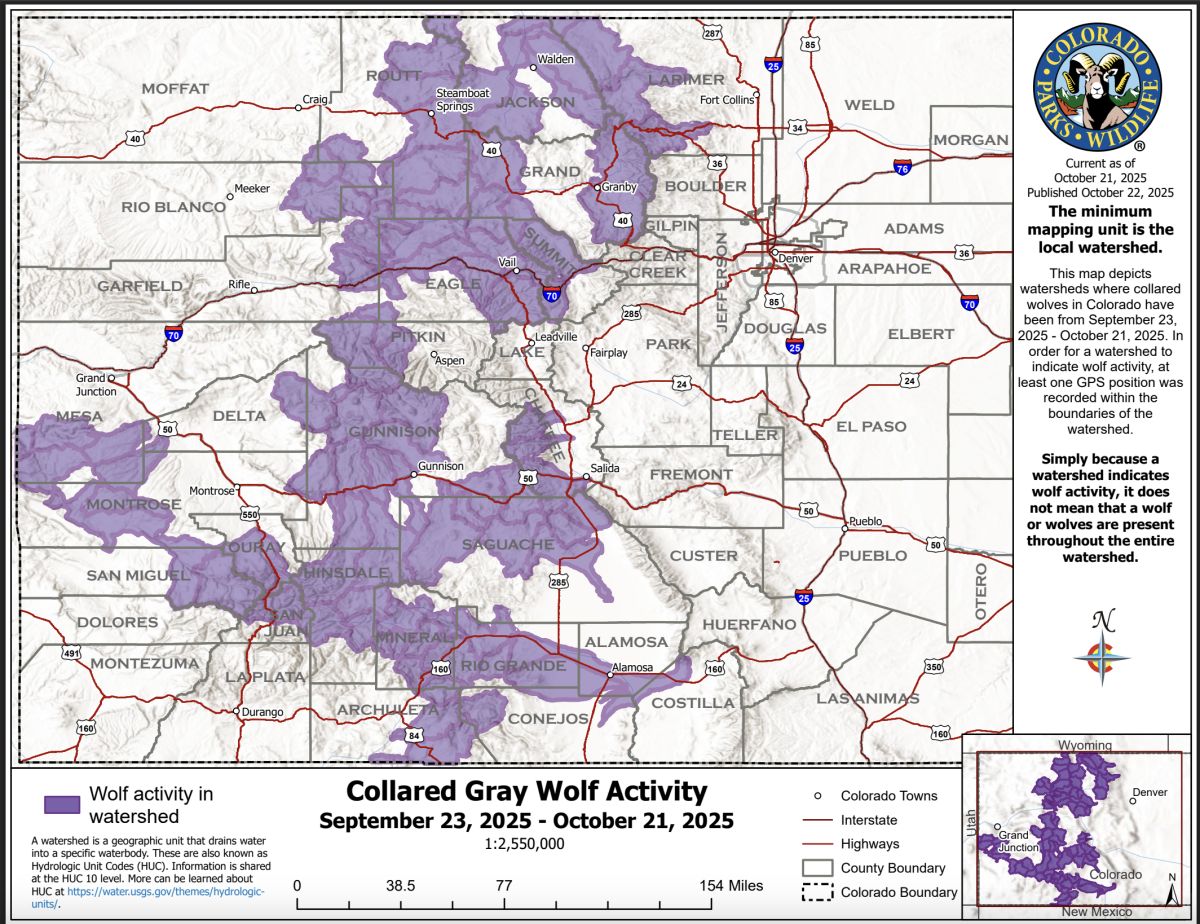

The map above depicts watersheds where wolves in Colorado were Sept. 23-Oct. 21, 2025. Below, it is in use as the Colorado Wolf Track Facebook page cover photo. (Colorado Parks and Wildlife map; Colorado Wolf Tracker Facebook page)

The map above depicts watersheds where wolves in Colorado were Sept. 23-Oct. 21, 2025. Below, it is in use as the Colorado Wolf Track Facebook page cover photo. (Colorado Parks and Wildlife map; Colorado Wolf Tracker Facebook page)

Information was withheld. Key people were omitted. Members of the media watched wolves step out of their crates and lope into the aspens. But no Grand County commissioners were invited, nor any from Summit County where the second five wolves were released days later.

More trouble followed as the wolves explored their new territory. Conway Farrell owns a ranch with sheep and cattle between where the Grand County wolves and Summit County wolves were released. And Doug Bruchez, whose ranch borders Farrell’s, said it took no time at all for some of the wolves to find both of their properties.

When one of the Grand County wolves and one of the Summit County wolves mated, they parked themselves near Farrell’s ranch, where the male wolf, at least, started preying on livestock.

Colorado’s wolf management plan had been approved without a definition of how many sheep or cattle wolves needed to kill before they were considered “chronic depredators” and could be removed. So even though the ranchers had proof the wolves were killing their animals, the agency couldn’t kill them. Then, in April 2024, CPW Director Jeff Davis said the agency wouldn’t shoot the male wolf blamed for the kills because based on data collected from their tracking collars, the female seemed to be denning. Killing her mate, he said, would make the pups’ survival unlikely, an act contrary to the state law directing CPW to establish a viable population.

They left the pair alone and pups were publicly confirmed in August 2024, when an outdoorsman captured video of three of the pups playing in an aspen grove.

Three gray wolf pups known to have been born in spring of 2024 in Grand County were observed by Colorado outdoorsman Mike Usalavage, who posted a video on social media Aug. 17, 2024 but did not reveal the location. (Colorado Parks and Wildlife)

Wolf advocates celebrated the historic moment for wildlife conservation. But not the citizens of Wolf Tracker. The wolves kept preying on Farrell’s livestock and he had become something of a symbol of all that was wrong with reintroduction.

One of Williams’ heroes is Erin Brockovitch, an environmental and consumer activist who gained fame for her role in a major lawsuit against Pacific Gas & Electric over groundwater contamination in Hinkley, California. Like the people she represented, Williams says, ranchers and farmers are an underrepresented community that “at least traditionally haven’t had much of a voice. And CPW dumped wolves on them without so much as letting them know.”

The Grand County wolves stayed near the easily accessible food source they’d found, killing 15 of Farrell’s sheep and adversely impacting at least 35 of his cattle. The state later paid him around $600,000 in compensation for the losses, but when they were happening, lots of people — ranchers and otherwise — were rattled.

This story first appeared in Colorado Sunday, a premium magazine newsletter for members. Experience the best in Colorado news at a slower pace, with thoughtful articles, unique adventures and a reading list that’s a perfect fit for a Sunday morning.

For months prior, the Middle Park Stockgrowers Association had been pressuring CPW to kill multiple wolves known to be preying on cattle in the area. As pressure mounted, and the new pups grew, CPW decided to trap the family group they’d named the Copper Creek Pack and asked for help from Bruchez and Farrell.

Federal and state trappers posted up in Farrell’s hunting lodge during a time the property would normally have been leased to hunters, Bruchez added. The ranchers were sworn to secrecy, and they kept it.

But Williams caught wind of the capture operation “from more than one source” and posted about it before it before CPW did, he said. He didn’t know what he’d done until much later, when someone told him he “kind of threw a monkey wrench in the operation by publishing at that time,” he added.

“Oh, well, gosh, that’s not good,” he thought. “I’ve got to be careful, being someone who tends to have a level of respect for our state agencies.”

CPW announced completion of the operation on Aug. 27, 2024. On Sept. 4, Davis wrote in a private email to several stakeholders interested in restoration, that “despite ‘all of the experts’ and massive headwinds from the extreme end of the ranching community, CPW and our partners will be successful in restoring wolves to Colorado while avoiding and minimizing conflict with the ranching industry.”

Wolf Tracker lit up when Willams posted the letter. He says it was the kind of information members deserve.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife released five gray wolves onto public land in Grand County on Dec. 18, 2023. Pictured is wolf 2302-OR, a juvenile female that weighed 68 pounds. Biologists were not sure the animal would breed in 2024 because of her age. (Jerry Neal, Colorado Parks and Wildlife)

Colorado Parks and Wildlife released five gray wolves onto public land in Grand County on Dec. 18, 2023. Pictured is wolf 2302-OR, a juvenile female that weighed 68 pounds. Biologists were not sure the animal would breed in 2024 because of her age. (Jerry Neal, Colorado Parks and Wildlife)

Moderating Wolf Tracker

After Williams started the page on Dec. 15, 2023, Wolf Tracker “went from one person (me) to 3,000” in two weeks, he said in an email.

By Sept. 4, 2024, the next time he could get analytics, that number had risen to 7,000. His membership is relatively low (around 13,000), he said, because when he created the page “it was important to keep it private so we didn’t have to deal with scammers, bots, spammers and fake profiles.” He thinks people come to it because they truly care about the issue, about the plight of ranchers and because “there was a real vacuum in the beginning in what was being put out by the CPW.”

“I mean we knew the wolves were coming, and then we knew it was done covertly. And from an organizational, behavioral public health standpoint … anytime you try to introduce a change into a population or an ecosystem which involves people, information is very important.”

Williams’ drive to hold truth to power has kept the 68-year-old doctor, writer, Navy vet and hunter busy watchdogging the Polis administration, providing commentary that makes his supporters fawn and opponents shudder, and one time, writing his own “news release” about a CPW operation to kill a chronically depredating wolf because he thought CPW’s wasn’t clear enough.

The tools, clockwise from upper left, John Michael Williams uses to inform, educate and keep his Colorado Wolf Tracker Facebook group members engaged: a photo from a fictional press release he created to because he felt Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s wasn’t clear enough; a ticker showing the number of days it was taking Colorado Parks and Wildlife to find and kill a wolf that had been preying on cattle in Pitkin County (the agency never did find the animal. Williams removed the meme when “we got to about 70 days,” and he decided it had served its purpose); and location pins, in red, yellow and green, showing the “general locations” of wolves. (Colorado Wolf Tracker Facebook page screenshots)

The tools, clockwise from upper left, John Michael Williams uses to inform, educate and keep his Colorado Wolf Tracker Facebook group members engaged: a photo from a fictional press release he created to because he felt Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s wasn’t clear enough; a ticker showing the number of days it was taking Colorado Parks and Wildlife to find and kill a wolf that had been preying on cattle in Pitkin County (the agency never did find the animal. Williams removed the meme when “we got to about 70 days,” and he decided it had served its purpose); and location pins, in red, yellow and green, showing the “general locations” of wolves. (Colorado Wolf Tracker Facebook page screenshots)

“There’s a difference between lack of transparency and secrecy,” he said, citing times he believed CPW legitimately withheld information about the location of wolves for their safety as opposed to times they’ve “actively tried to subvert a message or keep the public in the dark … where it may serve (their) purposes, but it does not serve the purposes of the public.”

He’s a student of Enos Mills, father of Rocky Mountain National Park, who “made some very interesting observations of wolves,” including that they’ll avoid humans and livestock if they’re conditioned to do so (by members being killed). He’s a public health physician licensed in four states who says he’s concerned for Colorado ranchers because wolves are “impacting their livelihoods, stalking their children and attacking their pets.” And he’s a proponent of social media as a mode of information sharing who knows that to keep his audience engaged he has to keep it entertained. “Social media isn’t The New York Times, it isn’t The Colorado Sun. It’s sort of a mix between the National Enquirer and maybe X and throw in a pinch of the New York Post and Mother Jones,” he said.

But about a year after he created Wolf Tracker, it took a new direction.

“Running amok and frightening citizens”

In November 2024, a coalition of 26 ranching, livestock and rural community organizations started pressuring CPW to pause wolf reintroduction.

A petition they presented to the state wildlife commission contained information about Farrell losing his livestock despite trying everything CPW had told him to do to keep wolves away, including “yelling, screaming, shooting empty cracker shells,” and using Critter Gitter animal repellers, flashing fox lights, livestock protection dogs, carcass management, night patrol and range riders.

The group said it wanted CPW to hold off on bringing any more wolves to the state until “specific wolf-livestock conflict mitigation strategies (were) fully funded, developed and implemented.”

Williams says he can sense emotional shifts on Wolf Tracker when certain things come to light. And he sensed membership spike after the repeated depredations on Farrell’s livestock. He “has his finger on the pulse” of the group “and the pulse can be fast and the body sweaty and not happy.” (“Or mellow. Breathing a sigh of relief,” he added.)

The page functions as an information-sharing arm about wolf locations, the rather swampy connections between our governor’s office and CPW, how to advocate, among others.

— Cory Gaines, Colorado Wolf Tracker member

When the petition appeared, some expressed cautious hope. But clouding it was a reminder that more wolves were coming to Colorado. “And once again, there was no information,” Williams said, even though prior to CPW bringing 15 wolves in from British Columbia, the agency did tell commissioners in Eagle, Pitkin and Garfield counties that they’d likely arrive in early January.

On Jan. 8, the state wildlife commission denied the ranchers’ petition. That could have fueled the anger starting to flare up on Wolf Tracker. But Williams was also directly responsible. He had been slowly leaking information that someone in Pitkin County had agreed to let wolves be released on their ranch.

Then one of his “sources” figured out which plane from Colorado-based LightHawk Conservation Flying had flown to British Columbia to get wolves, and Williams shared that information on Wolf Tracker.

The plane would land at either Aspen/Pitkin County Airport or Eagle County Regional Airport, he wrote. “Another hot tip…keep your eyes open!”

Sure enough, on Jan. 12, the plane carrying the wolves landed at the Eagle airport, as a couple who knew it was coming awaited its arrival. After watching CPW load the wolves onto three agency trucks, they followed and videoed them driving through Glenwood Canyon.

On Jan. 14, a second plane carrying wolves that was scheduled to land in Eagle County landed at Denver International Airport, which caused some to speculate that CPW had redirected it because of Wolf Tracker activity. But a CPW spokesperson said Davis moved the landing after learning the Eagle County airport customs desk was scheduled to be closed on the original date and the animals needed to go through customs.

On the 14th, two men dressed in camo and carrying AR-style rifles followed hints dropped by Williams, and reported by Colorado Politics, to the ranch, claiming they were sightseers out looking for wolves.

A screenshot of Williams’ tip about the plane had been emailed to Davis and CPW Deputy Director Reid DeWalt on Jan. 8 with a clip from an article in the Toronto-based Globe and Mail that quoted Farrell saying: “Now, we hate every wolf. My advice to everybody is start shooting and poisoning them.”

A note included with the message said, “By itself, it isn’t much but in a certain situation it could be seen as evidence.”

But in the end, no laws were broken – at least not on the page or at the airport. So no action was taken against Wolf Tracker members.

Even so, Julie Marshall, an activist, longtime journalist and former communications officer for Colorado Division of Wildlife, believes Colorado leaders, including CPW and members of the wildlife commission, are “afraid of doing the right thing by standing up to bullies and bad actors.”

“We need fearless leadership to speak up for wolves and good ranchers who want to coexist instead of derail wolf reintroduction,” she said, “but instead we get silence from leadership, which implies it’s fine to run amok with weapons, trespass and frighten citizens. I think the Wolf Tracker group sounds like vigilantes and are dangerous to public safety and especially to wildlife.”

Williams’ fans praise him, including Jerry Porter, who noted his “hard work of keeping all the misinformation and garbage out of this group!!” Lee Bruchez, Doug’s brother, highlighted the Wolf Tracker community’s “thoughtful support and discussion, particularly (by) John Michael.”

John Michael Williams talks about his Colorado Wolf Tracker Facebook page at his home in Colorado Springs. Williams created the page in 2023 as a place to post reports of wolf sightings and depredations in Colorado. (Mark Reis, Special to The Colorado Sun)

John Michael Williams talks about his Colorado Wolf Tracker Facebook page at his home in Colorado Springs. Williams created the page in 2023 as a place to post reports of wolf sightings and depredations in Colorado. (Mark Reis, Special to The Colorado Sun)

So, is Wolf Tracker vigilante?

In the world of vigilanteism, the most effective leaders “appeal to the disempowered. Are often anti-tax, anti-fed, anti-immigrant. And they empower people to feel like heroes by doing things like defending the Constitution,” says Betsy Gaines Quammen, a writer who covers radicalization in the West and vigilante groups like the Free Land Holders and Oath Keepers.

None of those appear to apply to Williams, but this might: They engage people who are searching for a cause, Gaines Quammen said in an interview.

Wolf Tracker members aren’t necessarily looking for a cause, but in wolves they have one.

And on the page they might find a group largely united in opposition of not one but two, three or four common enemies. Posts and comments show an overwhelming disdain for liberals, wolves, “wolf lovers,” Polis, Reis and the upper reaches of CPW leadership.

Proof lies in attacks like this one, posted on the Wolf Tracker page: “I just joined this group thinking it was a wolf lovers page just to keep track of what they (people) were up to. I’m pleasantly surprised to find it just the opposite. Shoot away!”

It’s also in more extreme ones, like this: “We are living in a State of tyranny…! I will draw this line in the sand. The day one of these pro wolf people assault a rancher over a wolf claim is the day we pick up our arms and make the Cliven Bundy standoff seem like a weekend vacation for these tyrants!”

But as Cory Gaines (no relation to Betsy), a Wolf Tracker member, physics instructor at Northeastern Junior College in Sterling and founder of the Colorado Accountability Project, wrote in an “open email” to The Colorado Sun and state Sen. Dylan Roberts after a Sun story published in February detailing the stakeout and chase from the Eagle County airport, the same vitriol found on Wolf Tracker can be found on Reis’ Facebook page.

“Colorado Wolf Tracker was not created in a vacuum, has not grown in a vacuum,” he added. And “unmentioned in (The Sun) article are the constructive roles it takes on for many who have concerns over wolf reintroduction. It does indeed take the place of some journalism: The page functions as an information-sharing arm about wolf locations, the rather swampy connections between our governor’s office and CPW, how to advocate, among others.”

A fair assessment. But even Williams admits the events surrounding the delivery and release of the wolves from British Columbia created “quite a bit of dustup” and he has some regrets over how they unfolded.

That’s why he removed all mention of the ranch in Pitkin County, the planes carrying the wolves and the events surrounding the release. And he says he tries to filter out comments by a minority of members who think wolves “just need to be wiped out and killed and have a hunting season for them, and, you know, (shoot-shovel-shut up) and the whole thing like that. I think that’s kind of repugnant, and it’s illegal. That kind of content doesn’t get posted. And if it does, I will try to remove it.”

Some critics of the page would like to see more effort.

“I used to follow the page more regularly, but my blood pressure really can’t handle it,” said Rob Edward, president of the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project, who has been involved in wolf restoration for 30 years. “I have a general Facebook profile that I follow it with, because when I was myself there and actually dared to say something in opposition to something John Michael said, I got beat down from every side, including by John Michael.”

Edwards says he knows the wolf restoration landscape backward and forward, including “most of the very deep arguments on both sides of the equation” as well as “the science against the science.” And he says what Williams is doing with Wolf Tracker “is not in the benefit of finding a way forward of actually separating hard data and facts from fiction, or helping people see the other point of view.” But, he added, “the same applies to ‘pro wolf’ groups where most of the nonsense is rancher and hunter bashing.”

The power of place

In May, after the British Columbia wolves had been released in Eagle and Pitkin counties, a wolf from the Copper Creek Pack killed four calves belonging to three different ranchers over a two-week period in the Roaring Fork Valley.

Interest on Wolf Tracker was high, because CPW had re-released the Copper Creek female and four of her five pups near the ranch the men had trespassed on (the male had died on arrival at the animal sanctuary and one pup was left behind. CPW shot it over the summer after it preyed on livestock in Rio Blanco County). By then, CPW had also adopted a definition of chronic depredation, and on May 28, the agency located and shot the depredating wolf. But the rest of the remaining Copper Creek wolves, plus new pups, remained in place, and a couple had zeroed in on calves on two ranches.

In July, Williams invited a surprise guest onto Wolf Tracker for an informal interview. It was Gary Skiba, a career biologist and CPW commission appointee who publicly resigned when he realized the Senate wouldn’t approve him “in the face of opposition from hunting, outfitting and livestock producer groups.” Unlike Edward, he had a more congenial experience with Williams despite his pro-wolf stance.

Williams asked Skiba a couple of hot-button questions sure to get a rise out of the Wolf Trackers. They did, but Skiba said Williams “very graciously” thanked him for taking the time to participate, and “admonished one poster who wrote a rather nasty message about me.” His “summary” of Williams, he told The Sun, is that “I don’t think his views on wolves are based solidly on facts in all cases, and we therefore disagree. That said, he was thoughtful and fair-handed towards me.”

Social media isn’t The New York Times, it isn’t The Colorado Sun. It’s sort of a mix between the National Enquirer and maybe X and throw in a pinch of the New York Post and Mother Jones.

— John Michael Williams, founder of Colorado Wolf Tracker

Josh Wamboldt, a Western Slope outfitter and frequent contributor, says he believes Williams “strives to keep balance on the page” that serves as “an informational piece” allowing people “to form their own opinion on issues, because you can get both sides of the argument.”

Wamboldt’s parents were the people staked out at the Eagle County airport, and he said the point of tracking the plane, “was to hopefully get a possible release sight and notify the people in those areas that wolves were just dropped.”

CPW’s lack of transparency has made it so “ranchers can’t even prepare before wolves are dumped at secret locations,” Wamboldt said. “I’ve heard tons of pro-wolf people state that for proper coexistence, it takes a proactive response, not reactive. This entire introduction has been reactive, ranchers don’t get notified until wolves are already knocking on the back door, they can’t get non-lethal measures until they have a depredation, and even then CPW is so short supplied they typically only give you enough to get by.”

But Mark Harvey, a rancher in Old Snowmass, believes “with a little bit more strategy, a little bit more energy,” Colorado could create a world where wolves, ranchers and livestock could coexist. “It’s been a rough start here in Colorado, but from what I understand, Wyoming, Montana and Idaho went through a similar process at the beginning. Things are much better in those states when it comes to managing livestock.” And solutions are where he thinks Williams should place his focus.

John Michael Williams walks on his property in Colorado Springs. In the foreground is a brass casting of an elk that belonged to his mother. (Mark Reis, Special to The Colorado Sun)

John Michael Williams walks on his property in Colorado Springs. In the foreground is a brass casting of an elk that belonged to his mother. (Mark Reis, Special to The Colorado Sun)

Howling into the future

At the moment, the future of Colorado’s wolf reintroduction is up in the air, however, now that 10 reintroduced wolves have died, including a collared female from British Columbia on Oct. 30 in southwestern Colorado, far from where she was released in January.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has also banned CPW from getting more wolves from British Columbia, saying the agency violated rules in its special Endangered Species Act permit regarding international sourcing.

They likewise banned the agency from getting wolves from Alaska, saying the 10(j) rule, that classified Colorado’s wolves as an experimental population and allows management strategies including lethal removal, also stipulates wolves must come from the “delisted Northern Rockies population area” of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, the eastern third of Oregon, the eastern third of Washington and north-central Utah.

And on Nov. 5, the Wildlife Service announced it no longer intends to issue a nationwide recovery plan for gray wolves, which the Center for Biological Diversity says is unlawful, because courts have repeatedly made it clear gray wolves have not recovered in places like the southern Rocky Mountains and West Coast.

The reaction of Wolf Tracker members to the announcement on Friday of the latest wolf death says more about the page than any interviewer or Williams could.

It was immediate and predictable.

“Hallelujah.”

“Great news for a Friday.”

“Colorado’s pathetic wolf lovers!!”

“Unfortunately, they are reproducing faster than they’re dying off.”

By mid-morning, Williams said he’d already deleted some “nasty comments” and took “no joy in reading that some people are happy about the death of this wolf.” But he had some words about the restoration.

“I understand why the introduction efforts must go forward, because of the voters’ approval of Prop. 114,” he wrote in a text. “But I would predict that we will see more wolf deaths and more polarization between all of the stakeholders. I’ve never enjoyed seeing animals caged in zoos, especially bears, big cats and mammals from Africa. The introduction of wolves, whether it be to Yellowstone or Colorado, makes me feel similarly — they have been removed from their natural habitat and dropped into a ‘zoo without walls’ … If there ever was a better time for a pause to reset and get both sides talking to find a better way, I can’t think of one.”

Type of Story: News

Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.